When I was a kid we played "War" all the time. I'm going back to the mid-'60s, so the war we fought was usually some undefined version of WWII, filtered through the TV series Combat!, with Vic Morrow and his troops as live-action supplements to DC comics' Sgt. Rock ("of Easy Company") and Marvel's deliriously titled Sgt. Fury and His Howling Commandos. We were fully equipped, one or more of us, with helmets, canteens, blades with belt-loop sheaths. The helmets were pure cornball, but the canteens were serviceable (although I shudder to think of the quality of the liquid inside after a few weeks in the field--or did my mother clean mine when I wasn't looking? It's likely; unless she was fed up--which made her clean grimly, head down, muttering in Spanish like Ricky Ricardo, except no one was laughing--I never noticed her ministrations; it seemed clean clothes and hot meals were just there, like the walls and furniture. Lucky me.); the knives/bayonets, though, were laughably useless, reassuringly (to parents) bendable things with no gutting power whatsoever. And of course the ordnance: a variety of plastic submachine guns, sidearms, and rifles, as well as copies of a local newspaper, rolled up tight and secured with a rubber band, that functioned as captured Kraut hand grenades (or billy clubs in another bit of mayhem we indulged in, "Escaped Convict." Let's just say we were a brutal posse, more brawn than brains when it came to subduing the fugitive); and I occasionally lugged around a broken but lethal-looking BB gun that had been my father's when he was a kid--and oh did he regale me with stories of REAL war games, 1930s style, in which all the kids had BB guns--and leather jackets, he swore, to absorb the impact of the BBs (I was always uneasy at this piece of information; what about head-shots, not to mention Jean Shepherd-esque eye-loss?); and the battles occurred at a dump, with hunks of concrete as lobbed grenades and barriers of scrap fortified with all manner of rotted lumber and trash. My father seemed to live in a whiz-bang world that was part Little Rascal, part Bowery Boy, one I'd like to write about at length some time; but let's get back to the mid-1960s. That BB gun was heavy, not my first weapon of choice, although it was darkly ominous, a ruined giant. We often played war against an invisible enemy; it seemed the point was slow advance and heroic, even romantic, expiration, usually involving all kinds of twisting, spinning and sprawling, with one's weapon flung with the force of pain and despair. And that was the problem: at such moments my father's gun became a deadly projectile, so I had to either hang onto it or carefully plot its trajectory away from my fellow soon-to-be Glorious Dead. This was unsatisfying. Death on the battlefield was a transcendent moment, an abandonment of self-control, then self, for good and all. One could not, in the midst of such cathartic freedom, such a medal-worthy demise, simply set one's gun down on the lawn, lest another kid get brained. So I often opted for a less hazardous firearm (aint it ironic?), one that would assume the proper air of reckless finality--without the possibility of contusion--as it spun away from my whirling form. A danse macabre of terrible, beautiful sacrifice. ("Tell my mother--gasp, choke--not to cry.")

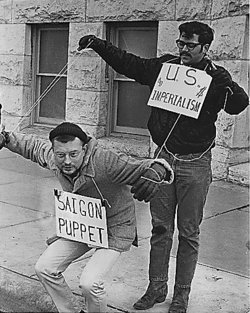

As I entered high school and had to register with Selective Service--not a real "draft card," with a number and an air of vibrating anxiety, but just preliminary paperwork; I was 18 in 1974, and we were officially out of Vietnam in '73--the war made me nauseous, despite my continuing love for war comics and movies. In my head I was always a pacifist. I couldn't bear to think of even the feeling of my bare fist on another person's face--in anger, that is; for fun, of course, we boxed with gloves and bounced each other around playing football (and in all honesty, there was also sibling-bashing, a form of hand-to-hand--or foot-to-shin--combat that seemed to circumvent all other moral imperatives); also, I was a real pest on social issues. I can still remember a debate our eighth-grade nun held: those in favor of capital punishment on one side of the room, those opposed on the other. While my memory encourages an inflated image of myself, so doubt may be in order, I'm still pretty sure I was the only one who stood on the "opposed" side. I can remember a bit of false pride at my lone stance, the self-satisfaction of the morally irritating. And I remember a drawing I did of Nixon in high school; he's Hitler with a skislope nose and jutting jaw, Bob Hope without timing, giving the ol' seig heil! while lines of bombers--secret ones, Cambodia-bound?--stream overhead. And we had some kind of variety show at my high school--I recall Georgie Jessell and Frank Gorshin were there--that ended with patriotic songs and the National Anthem. But, as I mentioned yesterday, at the time I was reading Kurt Vonnegut, and in Breakfast of Champions he describes "The Star-Spangled Banner" as "gibberish sprinkled with question marks"; and I refused to stand while it was played. I believe I was right, but what a price everyone around me had to pay.

I have carried this aesthetic-moral schizophrenia with me all my life. For instance, I know Doug Funnie's dad is wise because he once said, "Show me a man who resorts to using his fists, and I'll show you a man who's run out of good ideas." And I agree with Gandhi that one needs to be careful not to fall into aggression, since it takes all kinds of forms; as he points out, even a lawsuit is a form of warfare. My absolutism can be monumental and troubling, both to others and myself. But for years it's been the rock upon which I've been trying to build my whatever. Unfortunately, I'm also committed--or maybe just attracted--to some bad craziness, whether it's my well-documented mania for horror films, or video games like Doom, or creepy cartoons (Aqua Teen Hunger Force, The Venture Brothers, Ren and Stimpy), not to mention E.C. comics, the paintings of Francis Bacon, and the music of the Cramps. My friend Gene once mused that maybe I was like those people who can handle snakes and drink lye and not swell up/convulse and die. Now that would be a relief. But I suspect I'm just trying to have it both ways--or as many as I can--and while my open, yearning heart is filled with satyahgraha and the peace that passeth all understanding, my squirmy little brain smells a rat: me.

I have carried this aesthetic-moral schizophrenia with me all my life. For instance, I know Doug Funnie's dad is wise because he once said, "Show me a man who resorts to using his fists, and I'll show you a man who's run out of good ideas." And I agree with Gandhi that one needs to be careful not to fall into aggression, since it takes all kinds of forms; as he points out, even a lawsuit is a form of warfare. My absolutism can be monumental and troubling, both to others and myself. But for years it's been the rock upon which I've been trying to build my whatever. Unfortunately, I'm also committed--or maybe just attracted--to some bad craziness, whether it's my well-documented mania for horror films, or video games like Doom, or creepy cartoons (Aqua Teen Hunger Force, The Venture Brothers, Ren and Stimpy), not to mention E.C. comics, the paintings of Francis Bacon, and the music of the Cramps. My friend Gene once mused that maybe I was like those people who can handle snakes and drink lye and not swell up/convulse and die. Now that would be a relief. But I suspect I'm just trying to have it both ways--or as many as I can--and while my open, yearning heart is filled with satyahgraha and the peace that passeth all understanding, my squirmy little brain smells a rat: me.Am I being too mea maxima culpa on myself? Probably; but watching Gunner Palace (2004), I think I saw the bitter fruits of the divided mind. I enjoyed listening to the soldiers, especially their deadpan gallows humor, their combination smirk-sneer that kept them on their toes and straight in their heads. The counterpoint to this is the rappers, who have organized their thoughts in snaky couplets that work like telegrams of the bad news: Your son/daughter is Way Over There. I admired their wit, but I kept grinning at the jokers, the G.I. Joes like Stuart Wilf with his famous spiel on vehicles armored with scrounged scrap metal: "Part of our eighty-seven billion dollar budget provided for us to have some secondary armor to put on top of our thin-skinned Humvees. This armor is made in Iraq, and it's high quality ... metal ... and it will probably slow down the shrapnel so that it stays in your body instead of going clean through. And that's about it!" And the soldiers watching this bit laugh explosively, rat-a-tat, But the movie also makes you squirm, while the rat scurries by; as one soldier says, slowly, as though he's picking his way through brambles, "I don't think ... anywhere in history has someone killed someone else and something better has come out of it. It's just ... not possible."

Gunner Palace reminded me of those silly suburban afternoons I spent imagining the right death--with no right, of course--and of my jaundiced adolescent eye watching Nixon crank the meatgrinder. And I was worried for those soldiers, because I could hear aesthetic-moral schizophrenia messing with them, sending the right message, but disguised, like alien signals broadcast from their fillings, telling them they're craaaa-zee. My mother dismissed war as "young men playing old men's games," and I've never forgotten it--but once you're in the game, you gotta play. Those old men count on that, and it's what makes the soldiers in Gunner Palace so heroic and rueful, and their sacrifice so beautiful and terrible.

Gunner Palace reminded me of those silly suburban afternoons I spent imagining the right death--with no right, of course--and of my jaundiced adolescent eye watching Nixon crank the meatgrinder. And I was worried for those soldiers, because I could hear aesthetic-moral schizophrenia messing with them, sending the right message, but disguised, like alien signals broadcast from their fillings, telling them they're craaaa-zee. My mother dismissed war as "young men playing old men's games," and I've never forgotten it--but once you're in the game, you gotta play. Those old men count on that, and it's what makes the soldiers in Gunner Palace so heroic and rueful, and their sacrifice so beautiful and terrible.

No comments:

Post a Comment