I often wander aimlessly. I think I do this on purpose, if only so that I can be pleasantly surprised with what seem to be happy coincidences. A few days ago, I accidentally ran into Douglas Sirk's All That Heaven Allows (1955). In the blog that followed, I mentioned that one should catch Todd Haynes' Far from Heaven (2002) as a postmodern follow-up. Two days after that I'm watching Rainer Werner Fassbinder's Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974), a movie I had never seen--but had read of, and of which I knew the general outline. I was stunned by the fact that it was essentially a remake of the Sirk movie. Again, my willful ignorance pays off, so even at 49 I give myself the irreplaceable present of discovering a great film, as if I were a movie-hungry kid again. What fun it is; I'm glad I waited--or wandered into it.

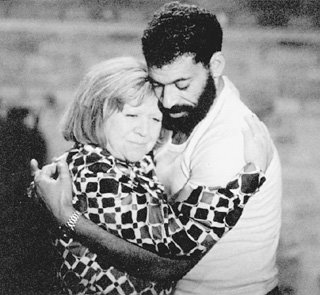

I often wander aimlessly. I think I do this on purpose, if only so that I can be pleasantly surprised with what seem to be happy coincidences. A few days ago, I accidentally ran into Douglas Sirk's All That Heaven Allows (1955). In the blog that followed, I mentioned that one should catch Todd Haynes' Far from Heaven (2002) as a postmodern follow-up. Two days after that I'm watching Rainer Werner Fassbinder's Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974), a movie I had never seen--but had read of, and of which I knew the general outline. I was stunned by the fact that it was essentially a remake of the Sirk movie. Again, my willful ignorance pays off, so even at 49 I give myself the irreplaceable present of discovering a great film, as if I were a movie-hungry kid again. What fun it is; I'm glad I waited--or wandered into it.Watching Fassbinder's movie is a trivial-pursuit treat. He replaces Rock Hudson's silky, manly gardener with a stolidly anxious Moroccan, pot-bellied and unblinking--but also muscled and affectionate. And Jane Wyman's character becomes a puffy cleaning woman, Emmi, sweet and lost, to be true, but also blotchy and stiff. Fassbinder gives us figures that both challenge us--to accept their love as much as we accept their blocky, assertive normality--and invite us; after all, most of us are closer to these two than Sirk's collectible figurines. More re-imaginings follow: Wyman's upper-crust coterie becomes Emmi's fellow charwomen--but still they keep their noses upturned, thusly! and move from Emmi as swiftly and surely as Jane Wyman's cocktail set. I especially liked the almost-comic rejection of the marriage by Emmi's children. In the Sirk movie, they stiffen and sniff, petulant and final. Emmi's children, though, gape at Ali as though he had two heads--or horns?--and one of them, remarkably re-inventing All that Heaven Allows's TV-as-Christmas-gift/manacle scene, deliberately kicks in Emmi's TV set--only to later bring her a new one, as part of a sequence that goes beyond Sirk into a more sober view of the weight of conformity and the mercenary heart of prejudice.

Just as things between Emmi and everyone else--including, in a Fassbinder complication, Ali himself--are at their worst, her enemies realize they need her (or Ali)--as a customer, as a workplace support, as a babysitter, and in the case of Ali, as an all-purpose strongman, cleaning out storage areas and so on--and the couple falls into favor with the world, just as they feel a rift between each other. This does parallel Sirk's movie, but in Fassbinder's case the couple, already married, drift apart as Ali continues to feel the weight of the race prejudice that replaces Sirk's classism. Everyone around him either disregards him or even openly insults his humanity. This, we know, has been his lot ever since emigrating to Germany. He meets Emmi at a crisis point, and the hatred his marriage magnifies drives him to plodding adultery--abetted in part by Emmi herself, who begins to allow the world's prejudices to seep into her own consciousness. She makes minor but telling comments about his "foreignness," and, in a quietly painful scene, even invites her friends to feel his muscles, as though he were a particularly appealing pack animal.

Ali collapses--like Rock Hudson's sudden tumble down the mountain--and Emmi learns of his condition, which the doctor informs him is common among immigrants: he has ulcers "brought on by stress." It's the pain of racism simultaneously made physical and internalized, literally eating at him. The film ends like Sirk's, with Emmi standing over her man, determined to help him--but in Emmi's case fearful the pain will not go away. Fassbinder, in expressing this uncertainty, claims Sirk's material for his own, and the movie becomes more than a game of trivial pursuit but its own sad creature, deliberate in its diagnosis, and more humane, I think, than Sirk's prettified dissection. Both films interrogate suspects, but I think Fassbinder's, in the quiet performances he encourages and the still and steady gaze of his camera, as unblinking as it is unmoving--and I see this in much of Jarmusch (I just watched Broken Flowers, more fluid than Stranger Than Paradise or Dead Man, but still willing to get out of our way and let us see)--but again, Fassbinder refuses to step on his punchlines; Ali's and Emmi's pains are bright and sharp enough on their own.

The result is a kind of reward for this Humble Viewer who has watched enough movies to connect some dots, but not so many--ah, but can there be too many?--that an occasional surprise, like Ali ..., can't suddenly appear after all these years to remind me, as a friend of mine recently wrote, "The universe of cinema is vast; it should contain multitudes." And--hooray for Hollywood, Bollywood, Indiewood, and all--it surely does.

No comments:

Post a Comment