Owning Mahowny (2003) provides Philip Seymour Hoffman with an opportunity of epic proportions to display his talent for implosion. The sight is unlike anything else I've seen in a movie; even Bill Macy's famous black hole impression in Fargo (1996) has a nervous energy, with a final backblast that relieves him and the viewer of the tension of being a fool. Hoffman gives himself no such catharsis; instead, he subjects us to 100 minutes of suffocation without the accompanying thrashing about, which would be relatively reassuring as it reveals the struggle for survival we would expect.

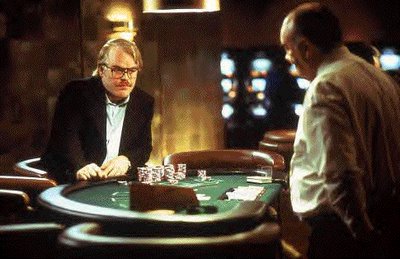

This is where Hoffman gets it right. His bank manager/gambling addict, based on a real person who stole over $10,000,000 (Canadian!) in less than two years, may be drowning, but strapped to the wheel as he is, we get not even a flinch. The guys who watch him through the eye in the sky at the casino call him "The Ice Man," and they're right, if they're thinking about one of those Paleolithic fellows found every once in a while suspended in a glacier, perpetually stunned that he's trapped and doomed. Hoffman's Mahowny may be hunting, like that caveman in the permafrost, but his only prey is his own desire, and he never grasps it firmly enough to register satisfaction--at one point he practically breaks the tables in two casinos, in both Vegas and Atlantic City. No, he is only capable of stunned dismay as he methodically shoves money at bookies and casinos, doing everything he can to guarantee the cold thrill he gets as the glacier moves him along.

One of the most interesting things about this movie is that everyone around Mahowny--his girl, his friend, the casino workers and managers, even his dimwitted bookie--stands amazed, appalled, delighted, outraged at his fall, and rise, and fall, while he remains stolidly plugged up, a grunting, hunched-over, constipated victim of his bad habit. It's like watching a glutton slowly get sick--without the upchuck. Hoffman moves through it all without ever looking anyone in the eye; his averted face, shiny and pallid, would be tragic if it were self-aware. For him, though, it's all about "a financial problem, a shortfall," not an addiction, so he can never expel the poison.

One of the most interesting things about this movie is that everyone around Mahowny--his girl, his friend, the casino workers and managers, even his dimwitted bookie--stands amazed, appalled, delighted, outraged at his fall, and rise, and fall, while he remains stolidly plugged up, a grunting, hunched-over, constipated victim of his bad habit. It's like watching a glutton slowly get sick--without the upchuck. Hoffman moves through it all without ever looking anyone in the eye; his averted face, shiny and pallid, would be tragic if it were self-aware. For him, though, it's all about "a financial problem, a shortfall," not an addiction, so he can never expel the poison.At the end, he makes what is for me a stunning admission: that, on a thrill scale of 1 to 100, gambling is a 100. But you can't tell from watching him. Every win seems merely the swing of a hammer breaking the wall between himself and failure--and the failure merely the hammer itself, which he carries with grunting dedication. But despite his best efforts--or maybe because of them; I am continually, happily duped by good performances--Hoffman makes me feel sorry for Mahowny, if only because it looks like it hurts so much. We're informed in a postscript that Mahowny went to jail for six years, and has yet to place another bet. But Hoffman's performance indicates the real wounds of addiction, which manage to pull a horrible trick: They may heal, but the pain does not fade. So Hoffman's cramped form lies like a last-gasp fish in the bottom of Satan's bass boat, too small to keep, too slippery to throw back.

No comments:

Post a Comment