So many images and impressions get in the way whenever a famous movie star delivers a performance that it becomes difficult to accept it on its own; we see every other performance superimposed on the one we’re watching, like multiple-exposure photographs--or archaeological layers, each level running atop another, striated multiplicities that can reduce any given performance to a parody of itself--or complicate it to confusion. Add to this the problems (opportunities?) of what James Naremore and others call "expressive coherence" (or "incoherence") in which actors "act" as we expect them to--or as their characters would, thus achieving "coherence"; or their characters (or performance styles) will run counter to our expectations of such a character or actor, resulting in "incoherence." Yikes.

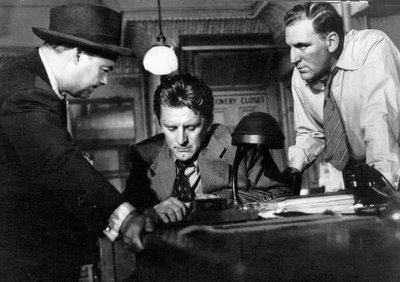

Kirk Douglas is the quintessence of this situation. I watched Detective Story (1951) last night, and he was at full Kirk tilt, all agonized twists and crimps, mixed with slanting satires of ease, his legs stretched like his grin, almost lanky and lithe, if he weren't so tightly wound. At times he even wears reading glasses, encasing his face like a weird grimace--or something like that; I dunno; as usual, he is mesmerizing and bizarre, confounding all best efforts to hold him still. At all times, though, he plays with coherence and incoherence, satisfying our needs--for the humor, strength, and intense focus his character needs as he made his way through a tense day at his precinct house--but also alarming us, either with those simple spectacles--or (I can't resist the pun) the spectacle of his fury, guilt, and disintegration as his iron-fast moral code swallows whole his job, wife and all, including his life.

I keep coming back to this movie, having seen it five or six times over the years. I have an affection for its scenario--again, a day in the life of a precinct house with Douglas' Det. Jim McLeod as its savagely beating heart--and supporting cast--William Bendix (one of my father's favorites, for him the gold standard of the grandeur a character actor can achieve), who plays Douglas' counterpoint and conscience, and Joseph Wiseman (also a guy my father admired) in a surreal, unhinged performance--almost in a matchup duel with Douglas'--presaging the hopped-up chaos of Jerry Lee Lewis--and man you gotta know it, Michael Richards’ Kramer on Seinfeld; giddyup!--and most of all its finale, in which the fatally wounded Douglas, who has walked into Wiseman's four-time-loser hail of gunfire, grinds out half of an Act of Contrition before dying--so that Bendix can finish it for him.

That last scene stands for every lasting virtue of a movie star's career, the archetypical breadth, the familiar electricity of decades of performances. And it proves part of Naremore's point, because Detective Story stands at the tip of Douglas' early career. He has gone on and on, of course, but by 1951 he had already been suave in Out of the Past (1947) and true-gritty in Champion (1949), and bound and determined in Young Man with a Horn (1950)--but I think 1951 is a watershed, the year he also starred in Ace in the Hole (a.k.a. The Big Carnival), a Billy Wilder torture engine that flays at the greed and thirst for glory that drives every media circus.

That last scene stands for every lasting virtue of a movie star's career, the archetypical breadth, the familiar electricity of decades of performances. And it proves part of Naremore's point, because Detective Story stands at the tip of Douglas' early career. He has gone on and on, of course, but by 1951 he had already been suave in Out of the Past (1947) and true-gritty in Champion (1949), and bound and determined in Young Man with a Horn (1950)--but I think 1951 is a watershed, the year he also starred in Ace in the Hole (a.k.a. The Big Carnival), a Billy Wilder torture engine that flays at the greed and thirst for glory that drives every media circus. So, as Naremore points out while discussing Hollywood actors in his book Acting in the Cinema, the Douglas we know from his later films colors our view of the earlier one, and vice-versa. And that influence makes the viewer swoon; as Det. Mcleod dies, I think of Spartacus and Van Gogh and Col. Dax in Paths of Glory, all dropping like lead, final, no rebound, shot in the heart by their personal codes, but still rising to greatness--except Det. McLeod, who may have amended his life too late to save his wife or himself, who could not fear the loss of heaven because he lived the pains of hell. Watching him hack at his life like a reeling woodsman, I have, every single time, shrunk in horror and wept in pity, warned and entreated by that silly cleft chin and those x-ray eyes, until Douglas achieves the coherence his career rests upon, a snarling insistence that, if you don't firmly resolve to detest all your sins, they will, as they are for every tragic hero, all be remembered.

No comments:

Post a Comment