Although I watch a dozen or so movies a week, I am by no means a true movie-geek, especially not one of the compulsive compleatists or trivial pursuers whose breath comes in short pants (there's a joke worthy of Groucho in there, if you want it) at the thought of a new Mario Bava blood-spattered color-wheel on DVD or a fellow geek's home-burned compilation disk of every B-Western scene that features the same rock outcropping in Monument Valley. True, I'm happy when I realize I've committed certain minor scenes to memory--I never get tired of mimicking the "wheat colloquy" in Woody Allen's

Love and Death (1975), with its "wheat ... wheat ... an enormous quantity of wheat"--or when I know some bit of trivia: For instance, Sam Raimi's masterfully simple "shaky-cam"--a camera mounted on a two-by-four, held by two people, who then run around with it, gliding it over tree stumps and car hoods--is the secret to all those giddy-scary demon-chases in

The Evil Dead (1981). But that's the kind of thing you can find under "trivia" on the Internet Movie Database--I checked; according to IMDb, star Bruce Campbell and Sam Raimi were often the ones running with the board. And thank goodness I didn't know that; the day that my movie-watching is about the obsessive-compulsive attainment of an encyclopedic knowledge of film, I'm through with it. Besides, the older I get, the less I recall. Doomed on all counts.

But each to his/her own, yes? The cinematic hobby-horse I love to ride is built on contrariness, a stubborn loyalty to films and actors and directors one cadre or another loves to bash. Oh, the thrill of Tom Cruise-boosting in certain quarters, or my unwavering support of Matt Dillon--and there you go, rewards do come, as Matt showed (or reminded) 'em all with his performance in

Crash. Or more exciting, the slight snobbism of maintaining

Punch-Drunk Love and

The Cable Guy are the only Adam Sandler and Jim Carrey, respectively, movies that matter,

Man in the Moon and select moments from

Anger Management notwithstanding. Not to mention my commitment to typical nerd delights, such as big-bug '50s movies or the "Carry On" series.

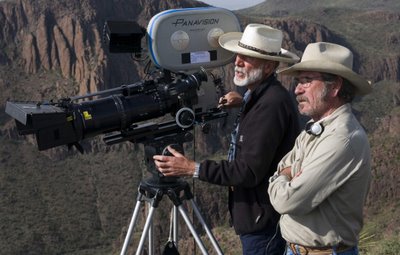

But such gadflying pales beside my insistence that certain directors can do no wrong. Michael Cimino, for instance. Anybody can find reasons to admire

Heaven's Gate, but I see moments of grandeur in

The Sicilian. True, I've never watched 1996's

Sunchaser--who has? I'm not even sure it's on DVD. But there is a distinct, albeit perverse, pleasure in Cimino-philia--and not, it is important to note, as a guilty pleasure; heck, even the ultra-cool super-dudes of cinema--read: Tarantino-- can crack wise about hipster-doofus junk like '70s all-girl hit-squad flicks or tilt-o-rama Japanese groovy-gangster epics. No, the Director Protection Program requires a steady hand, an unwavering fealty that passeth all understanding--even, at times, for me. But half the fun is digging in, refusing to be wrong. It is a skill developed as a boy in an argumentative household, then honed under the watchful eyes of the Jesuits, and sustained by contentious, beloved friends, whose affections to this day hammer at my adamantine chains of conviction.

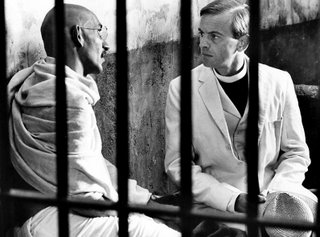

Which brings me to Brian De Palma. It's easy to take him apart: part Hitchcock rip-off artist, inappropriate humorist, and delirious disdainer of the very presence of the audience, De Palma can be seen as an Ed Wood with talent. But my admiration is not all that contrarian; he does have his not-so-secret society of near-worshippers. According to the Museum of the Moving Image's Program Notes for a 2001 De Palma retrospective, Pauline Kael wrote in

The New Yorker, "

Dressed to Kill seems to have merged De Palma's two sides: he has created a vehicle in which he can unify his ominous neo-Hitchcock lyricism with the shaggy comedy of his late-1960's

Greetings days ... in his hands, the thriller form is capable of expressing almost everything--comedy, satire, sex fantasies, primal emotions." But those same Notes, ah, note, David Thompson's response: "De Palma's eye is cut off from conscience or compassion. He has contempt for his characters and his audience alike, and I suspect that he despises even his own immaculate skill." David Thompson, we should note, often has his suspicions; it is a part of his greatness as a writer on film--and a "novelist"; seek out his movie-melding wonder,

Suspects, for a big astringent swallow of his own brand of contempt.

But I digress.

I agree to some extent with both Kael and Thompson. You can, too: Just watch

Snake Eyes (1998). I Netflixed it for the sake of its famous opening long take; my film class at our local correctional facility was going to watch

Goodfellas, and, among other things, I wanted them to compare long takes, as Henry and Karen go to the Copa--and one more, as the car bomb goes off in

Touch of Evil. I had forgotten, though, how protracted the long take was in

Snake Eyes, and how complicated--and there's your "lyricism" and "immaculate skill"--but also how important the scene, how much we learned, not only about the plot and the characters, but, most important, the tone and mood of the whole film, and its

Rashomon-like fracturing of the crime--but with the intent of clarifying, not obscuring, it.

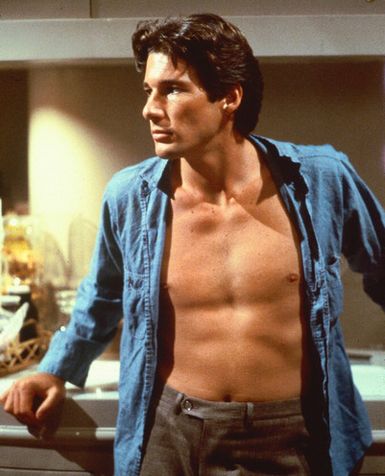

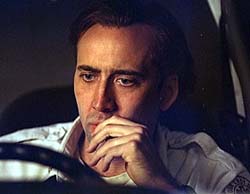

I think that opening sequence explains--maybe even justifies--my attraction to De Palma movies. As Kael points out, De Palma knows how to make his obsessions serve his needs. The film rewards us well for paying close attention to everything that happens--but, again, more than information we receive a sense that the Atlantic City casino in which the action takes place is a tightly wound, internalized world, with its own rules--but narrowing prospects. Despite the thirty-plus floors of rooms, arena, and massive underbelly, Nicholas Cage's Rick Santoro, a crooked cop with a caffeinated jive that seems boundless, is careening toward a trap, as the casino's eyes-in-the-sky record every moment, impaling both hero and villain, a chase watched, rewound, and watched again. So De Palma feeds our

Rear-Window voyeurism, forcing us to not look away, not even for a moment, or you'll miss the one small sign--a reflection of a face in chrome, a slight spray of blood--that lays it all out. De Palma uses that long take to wrestle the periphery into clear view, and the rest of the movie becomes a reward for close observation of Rick Santoro's gliding, jarring course into a mystery whose key is the last thing he needs, as the truth is nothing but betrayal and descent.

De Palma's movies circle this territory with admirable frequency. We are encouraged to watch, and rewarded mightily for doing so--then punished. So OK, maybe there's some contempt for the audience. But that's part of the De Palma thrill, because I don't think he really hates us; just our can't-say-no attitude to the pleasure of watching. Sometimes, as in

Carlito's Way, it gets beautifully tragic, the devilish glee of voyeurism enlisted in the cause of pity and compassion. At others, as in

Snake Eyes, the end is rueful but cool, a whatta-ya-gonna-do shrug sweetened with a kiss--and a kiss-off, sly but not snide, world-weary but not cynical. As Rick tells his in-hot-water friend, "It isn't lying! You just tell them what you did right, and you leave out the rest!" In De Palma's case, as far as I'm concerned, what he leaves out isn't worth seeing.

I'm not sure if Tykwer's movie is better or worse for having been made so relatively recently; after all, it seems, with its self-conscious multiple-version narrative, to be simply playing a game--and it actually announces itself as one, with a soccer ball (it is a German movie, after all) kicked high in our faces--and a game that was getting a bit long in the tooth by the late '90s. On the other hand, watching it again was still exciting: Its techno soundtrack, herky-jerky pace, time-travel snapshot sequences, and general exuberance once again grabbed me like Lola (Franka Potente) herself, still a sight to behold, a ripe fruit on the go, Milla Jovovich with an appetite. A Lola-come-lately it may be, but this movie still makes me grin.

I'm not sure if Tykwer's movie is better or worse for having been made so relatively recently; after all, it seems, with its self-conscious multiple-version narrative, to be simply playing a game--and it actually announces itself as one, with a soccer ball (it is a German movie, after all) kicked high in our faces--and a game that was getting a bit long in the tooth by the late '90s. On the other hand, watching it again was still exciting: Its techno soundtrack, herky-jerky pace, time-travel snapshot sequences, and general exuberance once again grabbed me like Lola (Franka Potente) herself, still a sight to behold, a ripe fruit on the go, Milla Jovovich with an appetite. A Lola-come-lately it may be, but this movie still makes me grin. And more. I had forgotten about Lola's yell, capable of shattering glass, drawing absolute attention--and, in the stunning casino scene, revealing its true power: to alter reality, tip the scales, load the dice--or, OK, fix the wheel--to make it all turn out right. By the third twenty-minute go-round of Lola's fateful haste, she ascends the final height--and no matter that Manni (Moritz Bleibtreu) no longer needs the money; she shows us what she is worth, and it's more than the 100,000 marks her boyfriend needs. In two quiet interludes, Lola and Manni consider their places in the other's heart, and we see that, despite all uncertainties, all the Butterfly Effects of moving from point A to B, "the heart knows what it knows," as Stephen King (!) quotes someone somewhere.

And more. I had forgotten about Lola's yell, capable of shattering glass, drawing absolute attention--and, in the stunning casino scene, revealing its true power: to alter reality, tip the scales, load the dice--or, OK, fix the wheel--to make it all turn out right. By the third twenty-minute go-round of Lola's fateful haste, she ascends the final height--and no matter that Manni (Moritz Bleibtreu) no longer needs the money; she shows us what she is worth, and it's more than the 100,000 marks her boyfriend needs. In two quiet interludes, Lola and Manni consider their places in the other's heart, and we see that, despite all uncertainties, all the Butterfly Effects of moving from point A to B, "the heart knows what it knows," as Stephen King (!) quotes someone somewhere. Lola not only keeps it together, she makes it happen, with every step and misstep, graceful bound and stumbling lurch. Without her, Manni would not only be sunk, he'd be not-Manni; by the end, you get the feeling Lola is no longer reacting, but creating. Lucky for us, she keeps running, or we'd go out like the small candles we are.

Lola not only keeps it together, she makes it happen, with every step and misstep, graceful bound and stumbling lurch. Without her, Manni would not only be sunk, he'd be not-Manni; by the end, you get the feeling Lola is no longer reacting, but creating. Lucky for us, she keeps running, or we'd go out like the small candles we are.