The term ended yesterday for my students at the prison. In American Literature I, we looked at the humanitarian strain of Romanticism, those who urge us to face Thanatos so that we may live, like a waterfowl swallowed up by the abyss of heaven, like a ship of pearl with many mansions--or those such as Lincoln, who feign modesty as he insists we'll little note what he has to say about how we cannot consecrate any ground on which we do not sacrifice ourselves; or Frederick Douglass, who first sought sheer literacy; then, when he has it, clamps on it and refuses to let go, as he will not Mr. Covey--the man who beat him once too often--until the master relents, and never again beats the man who is no longer a slave. As a grad school professor of mine once wrote at the end of one of my more perorational essays, "drums, thunder, and curtain."

In Introduction to Film Art, though, the curtain was messier: blood-red, profane, and ruthless--just the way we like 'em--a cinematic OD that was DOA: Goodfellas, with its broad and desperate cackle--"See? I'm enjoyin' every minute of this!"--but with watchful eyes, flat and measuring--and mistaken all along: The ledge was narrower than Henry Hill could have imagined, and his skittering fall, arms pinwheeling like Harold Lloyd with the cocaine blues, splatted him on the concrete like a plate of egg noodles and ketchup, the schnook.

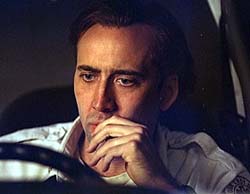

I always insist on a Scorsese movie. I refuse to indulge in outright competition in such matters, but he still seems to me to be the one to watch, the director who can still open up a film like a magician unfolding the box in which not one or two, oh no, but six-seven-eight and on surprises spill out, his hands nimble, his eyes still sharp. Watch Howard Hughes crash his plane or insist one can bring in the milk: Scorsese works like a young Turk bragging about what he's capable of. Or maybe even better yet, Bringing Out the Dead, a shameless coupling, right there in garish New York reds and smearing yellows, of the old story of salvation with some crankhead "with his hands on his own hardware." Add to that the movie supergeek Scorsese, cataloguing in his head--and film by film, on the screen--every shot he ever saw that meant something, anything, to the topography of movies; and I for one am always satisfied--while still hungry for the next sausage-n-peppers plate he'll serve up.

I always insist on a Scorsese movie. I refuse to indulge in outright competition in such matters, but he still seems to me to be the one to watch, the director who can still open up a film like a magician unfolding the box in which not one or two, oh no, but six-seven-eight and on surprises spill out, his hands nimble, his eyes still sharp. Watch Howard Hughes crash his plane or insist one can bring in the milk: Scorsese works like a young Turk bragging about what he's capable of. Or maybe even better yet, Bringing Out the Dead, a shameless coupling, right there in garish New York reds and smearing yellows, of the old story of salvation with some crankhead "with his hands on his own hardware." Add to that the movie supergeek Scorsese, cataloguing in his head--and film by film, on the screen--every shot he ever saw that meant something, anything, to the topography of movies; and I for one am always satisfied--while still hungry for the next sausage-n-peppers plate he'll serve up. As we watch a film, I ask my students to write an answer to a question I put on the board. For Goodfellas it was, "Pick a scene that illustrates Scorsese's mixed feelings toward his subject." As usual, I asked them to pay attention not just to WHAT is happening but HOW it does; my tired old joke is that I'm dedicated to ruining their future movie-watching experiences, forcing them to notice camera placement, lighting, sound, shot length and sequence, and on and on, a self-conscious exploded diagram of the emotion-producing machine. Or, to use the earlier metaphor, swiped from Welles, their job is to figure out the trick, steal fire from the magician's fingertips even as he sparks it out with his time-tested flourishes and misdirections. To clarify the question, we considered a hypothetical scene of clowns performing at a circus, as filmed by someone who knows they're funny and beloved by millions, but is also afraid of them. How would he shoot them? So we discussed tilted frames and extreme closeups, strobelights and jumpcuts. I think they've gotten pretty good at this: Last week, they watched Jimmy Stewart and Kim Novak pretty closely, noting the "mise en" a "scene" of their choosing, and capturing the techniques used to convey the scene's mood or importance to the film as a whole--or simply the preceding and following scenes. They're taking small steps, but as they go along I think they're peering at the terrain more closely.

I've read about a third of their answers, and I'm happy to say more than one of my students has noticed that Scorsese's wiseguys keep saying they're having a great time, but they are either eternally suspicious of one another or have, ahem, odd perceptions of what it means to be happy. Now, I'm not saying my students see Henry as anything but someone who "always wanted to be a gangster"; I think, though, they're feeling the weight of the film's techniques as it drags them toward the characters' reckless assertion and inevitable decline. It was the last day of class, and I was letting them leave if they'd finished writing the assignment. Most took me up on it, but four or five hung around to finish the movie. One student in particular kept his paper in front of him, writing quickly as the credits rolled. As he handed in the assignment he told me he'd seen Goodfellas before, but couldn't remember the song that played at the end, but as he recalled it somehow fit. We agreed that Sid Vicious singing "My Way" was an inspired choice, as Henry's parting shots at the square life are accompanied by an anthem for the self-apocalypse. It was funny, scary, and stupid, like Joe Pesci's Tommy De Vito, "a funny guy," and like Sid himself, who also cracked under questioning, so to speak.

After twenty years, our local community college is shutting down its program at the prison. I've heard another school may take its place; whether it allows me to offer a film course remains to be seen. In the meantime, at my regular job I'll be assisting a student who wants to complete an independent research project on docs. Something to do with children, I think. It won't be the same as the seat-of-the-pants hijinks we'd sometimes pull at the prison--What do academic felons really think of Gene Kelly in a leotard?--but between one Humble endeavor and another, I'll try to keep my hand in, as I hope will my students over the hill and, for now, far away. Of course, we'll always have Blogger.

After twenty years, our local community college is shutting down its program at the prison. I've heard another school may take its place; whether it allows me to offer a film course remains to be seen. In the meantime, at my regular job I'll be assisting a student who wants to complete an independent research project on docs. Something to do with children, I think. It won't be the same as the seat-of-the-pants hijinks we'd sometimes pull at the prison--What do academic felons really think of Gene Kelly in a leotard?--but between one Humble endeavor and another, I'll try to keep my hand in, as I hope will my students over the hill and, for now, far away. Of course, we'll always have Blogger.

No comments:

Post a Comment