In Surprised by Joy, C.S. Lewis complains that reading newspapers leads to "an incurable taste for vulgarity and sensationalism and the fatal habit of fluttering from paragraph to paragraph to learn how an actress has been divorced in California, a train derailed in France, and quadruplets born in New Zealand." He was arguing against the veracity of journalism in general, but in these comments he gets closer to a contemporary problem, which lies in the ability, via one electronic media or another, to "flutter," not in aerial beauty, like Forrest Gump's feather, but with a fractal's whim, one pattern giving way to another, until the lines between comedy, tragedy, fact, fiction, observation, and participation all become more than blurred, but erased. It worries me sometimes; such casual veering can lead to moral vacuity, an infinite "WHAT-ev-errrr" that would echo like thunder, if there were any boundaries, borders, or walls to contain the sound. But it is as good as infinite, and as full--or, sorry to sound facile, empty; but it's true: plugged in, those of us in the technologized, democracized, globalizing nations can sail blithely past death and doom until we get to the funniest home video or million-dollar, last-chance-to-call bargain--or worse, the agitprop bludgeoning of whatever "lying liars" we choose to believe--for as long as it fits our need of the moment. John Donne's most famous sermon is voided, because, caught in the electric current, I am an island, and no one's death affects me. And so OK, here it comes, the corniest irony of them all: having so much information, so many arresting images, half-truths, outright lies, and inviting sounds at my disposal, I'm asked to empty my self to make room. Filling up, I'm emptied. Plugged in, I'm isolated.

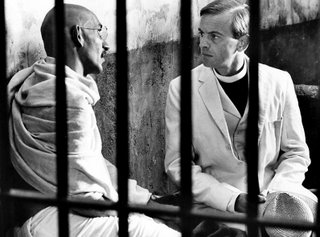

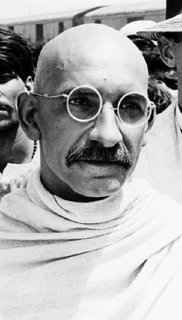

Case in point: Yesterday I watched Sunset Blvd. (1950) and half of Gandhi (1982). This is not, it seems, a double feature conducive to integrated moral reflection. Billy Wilder takes a machete to Hollywood, even while sympathy draws down the corners of the eyes--as it does Cecil B. DeMille's, who is tender toward Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson, engaging, like that master masochist, Lon Chaney, in an act of self-evisceration)--yes, until it's time to get back to work. As kind as C.B.'s treatment is, it is still the "kiss-off" he earlier disdains. This is a horror film of the cruelest kind, forcing the victims to watch their own slaughter, as in Michael Powell's Peeping Tom (1960)--but face-down, dead in the pool, narrating the decline--again, just as Swanson leers madly at her own past, "out there in the dark." Meanwhile, Richard Attenborough canonizes The Great Soul, moving with stately adoration through a gallery of the better and better acts of a man moving upward toward the only light that matters. I'll watch the rest of it today, but for now these two films co-exist, overlapping, intrusive, Lewis' vulgarization of tragedy.

Case in point: Yesterday I watched Sunset Blvd. (1950) and half of Gandhi (1982). This is not, it seems, a double feature conducive to integrated moral reflection. Billy Wilder takes a machete to Hollywood, even while sympathy draws down the corners of the eyes--as it does Cecil B. DeMille's, who is tender toward Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson, engaging, like that master masochist, Lon Chaney, in an act of self-evisceration)--yes, until it's time to get back to work. As kind as C.B.'s treatment is, it is still the "kiss-off" he earlier disdains. This is a horror film of the cruelest kind, forcing the victims to watch their own slaughter, as in Michael Powell's Peeping Tom (1960)--but face-down, dead in the pool, narrating the decline--again, just as Swanson leers madly at her own past, "out there in the dark." Meanwhile, Richard Attenborough canonizes The Great Soul, moving with stately adoration through a gallery of the better and better acts of a man moving upward toward the only light that matters. I'll watch the rest of it today, but for now these two films co-exist, overlapping, intrusive, Lewis' vulgarization of tragedy. But even as I watched Sunset Blvd., I saw that random access can be re-configured by one's own devices--and with one's literal devices, as the DVD player, the broadband connection, the text message and all can be enlisted in the service of pattern and purpose. I'm reminded of a kind of game I used to play in college, dialing the radio slowly along the FM band, allowing whatever was on one station to slide into the next, instantly creating connections, a self-invented meaning made in partnership with essential chaos. And just to prove how cool I (think I) was: In his liner notes for My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, Brian Eno reports that, "in 1951, John Cage composed 'Imaginary Landscape No. 4,' a piece for twelve radios, each with two players who control parameters." According to one of the performers, the "'snatches of music and speech ... with lengthy silences in between ... had a disturbing effect.'" But I think what is disturbed is silence, and the dominion of randomness. Art makes life, it seems. So as Billy Wilder took apart the things he hated with ruthless glee, on that sardonic grin I saw the second smile, slight, somewhat studied, but in the end pure with soul-force, that Ben Kingsley's Gandhi left on the electron stream of my Hitachi; and the Mahatma may have suffered a bit in the doubling, but still, poor Norma was rescued from absolute disregard, and became more than a horrible joke, but something closer to pity, undeserved or not. Watching both, one after the other, I knew I did not have the right--or at least the ability--to make that choice. Not with Gandhi watching, at least.

But even as I watched Sunset Blvd., I saw that random access can be re-configured by one's own devices--and with one's literal devices, as the DVD player, the broadband connection, the text message and all can be enlisted in the service of pattern and purpose. I'm reminded of a kind of game I used to play in college, dialing the radio slowly along the FM band, allowing whatever was on one station to slide into the next, instantly creating connections, a self-invented meaning made in partnership with essential chaos. And just to prove how cool I (think I) was: In his liner notes for My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, Brian Eno reports that, "in 1951, John Cage composed 'Imaginary Landscape No. 4,' a piece for twelve radios, each with two players who control parameters." According to one of the performers, the "'snatches of music and speech ... with lengthy silences in between ... had a disturbing effect.'" But I think what is disturbed is silence, and the dominion of randomness. Art makes life, it seems. So as Billy Wilder took apart the things he hated with ruthless glee, on that sardonic grin I saw the second smile, slight, somewhat studied, but in the end pure with soul-force, that Ben Kingsley's Gandhi left on the electron stream of my Hitachi; and the Mahatma may have suffered a bit in the doubling, but still, poor Norma was rescued from absolute disregard, and became more than a horrible joke, but something closer to pity, undeserved or not. Watching both, one after the other, I knew I did not have the right--or at least the ability--to make that choice. Not with Gandhi watching, at least. This kind of thing happens to us Humble Viewers all the time. I hope I can always connect the dot-matrixes, right or wrong, reinventing the Box as a frame for the collage each viewing contributes to, adding a small thing here and there, not fluttering vacuously but inventing meaning--and sometimes discovering it, what a treat--with each and every byte.

This kind of thing happens to us Humble Viewers all the time. I hope I can always connect the dot-matrixes, right or wrong, reinventing the Box as a frame for the collage each viewing contributes to, adding a small thing here and there, not fluttering vacuously but inventing meaning--and sometimes discovering it, what a treat--with each and every byte.

No comments:

Post a Comment