(MINOR SPOILER ALERT)

In the final scene of Roman Polanski's version of Oliver Twist (2005), Oliver (Barney Clarke) insists his benefactor, Mr. Brownlow (Edward Hardwicke), allow him to visit Fagin (Ben Kingsley, phenomenal once more), condemned to death, and beyond the pale of all approach. Awed by mercy, Oliver attempts to soothe his one-time friend--and I quote from the novel, which I believe at this point in the scene Ronald Harwood's screenplay does as well: "Let me say a prayer. Do! Let me say one prayer. Say only one, upon your knees, with me, and we will talk till morning."

In the novel, Mr. Brownlow "thinks it well" Oliver should see Fagin; and "Oliver nearly swooned after this frightful scene, and was so weak that for an hour or more, he had not the strength to walk." In the film, however, Oliver sits in the coach, melancholy but clear-eyed, and Mr. Brownlow looks over at him, realizing what a source of virtue and strength all this has made Oliver, now literally placed in Brownlow's hands, as he puts his arm around Oliver, in part comforting, but in part I think also drawing strength himself from a boy made by cruel institutions and kind hearts into something wiser than his years, and more kind than most children could manage. The screenplay also leaves out the Dickensian connection between Brownlow and Oliver, one of those stunning revelations of kinship that some find a bit contrived in Dickens--but which for me always are emblems of Dickens' belief in the interconnectedness of souls--and a warning to be careful whom you slight, because your lives will ensure a return--and, in Dickens, a comeuppance.

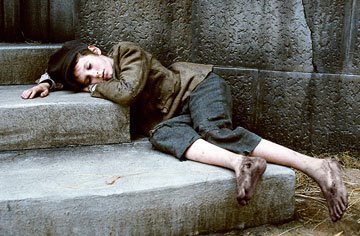

But I don't mind losing that cosmology in Polanski's film: his end leaves us with another Dickensian emblem: the child who may be heard, like Blake's chimney-sweeps, "Crying 'weep! weep! in notes of woe," a victim of "God and His priest and king, / Who made up a heaven of our misery," but who also shines in his sacrifices; again, as Blake in his more innocent mood sings, "I a child, and thou a lamb, / We are called by His name." Polanski's movie works for me like a Blakean dialogue--I was pleased, for instance, to see the orphans' beds looking like Blake's sweeps', their raised sides and black rectangles "coffins of black," where one orphan exclaims, "I'm so hungry I'm scared I might eat the boy that sleeps next to me."

But I don't mind losing that cosmology in Polanski's film: his end leaves us with another Dickensian emblem: the child who may be heard, like Blake's chimney-sweeps, "Crying 'weep! weep! in notes of woe," a victim of "God and His priest and king, / Who made up a heaven of our misery," but who also shines in his sacrifices; again, as Blake in his more innocent mood sings, "I a child, and thou a lamb, / We are called by His name." Polanski's movie works for me like a Blakean dialogue--I was pleased, for instance, to see the orphans' beds looking like Blake's sweeps', their raised sides and black rectangles "coffins of black," where one orphan exclaims, "I'm so hungry I'm scared I might eat the boy that sleeps next to me." In this self-aware follow-up to The Pianist (2002), Polanski continues to explore the fruits of the hard labor of abandonment, cruel treatment, deprivation, and fear. His Oliver not only survives, though, but becomes a better person. Polanski has said he wanted to make a film for his children, and his Oliver Twist tells them a "moral tale" whose horrors are not merely cautionary, the heartless scolding of " ... if all do their duty, they need not fear harm" (Blake again), but a promise that suffering can have meaning--and that it can come to an end. Polanski's finely, grimily detailed London--the film opens and closes with nineteenth-century prints and etchings of daily British life, "smeared, bleared"--is Oliver's proving ground; but it is also where he provides opportunities for others to prove themselves, from Nancy to Fagin to the Artful Dodger, and in the end to his adoptive father. Mr. Brownlow has most certainly rescued Oliver; but he has gained at least as much in return: Polanski offers him a noble soul to learn from; as he muses in both film and novel on first meeting Oliver, "There is something in that boy's face ... something that touches and interests me. Can he be innocent? ... Bless my soul!--where have I seen something like that look before?" In the book, this is our first hint of Dickens' version of the Great Chain of Being, in that we are all relatives. In the film, though, it seems closer to a realization that the "something" Brownlow notes is Oliver's rare, even noble, ability not to be decimated by suffering.

In his novel, Dickens rails against the institutions that bring Oliver pain, and his anger is typically, perversely expressed in the most sadistic treatment of the boy Dickens can get his England to muster. It can be harrowing to read much of this; Polanski--despite being, after all, Polanski--shows amazing restraint as he lightens Dickens' cruel touch, constructing a children's film that does lead us into the dim, close quarters where officiousness, greed, and fear make the air filthy, but with Oliver he opens a window just enough to allow in that last wafting breeze, as Oliver sits solemnly in the coach, and Brownlow counts their blessings for both of them.

In his novel, Dickens rails against the institutions that bring Oliver pain, and his anger is typically, perversely expressed in the most sadistic treatment of the boy Dickens can get his England to muster. It can be harrowing to read much of this; Polanski--despite being, after all, Polanski--shows amazing restraint as he lightens Dickens' cruel touch, constructing a children's film that does lead us into the dim, close quarters where officiousness, greed, and fear make the air filthy, but with Oliver he opens a window just enough to allow in that last wafting breeze, as Oliver sits solemnly in the coach, and Brownlow counts their blessings for both of them.

No comments:

Post a Comment