His father was the animator Max Fleisher, who worked with his uncle Dave. I've read Richard intended to study medicine, but how could he concentrate, with Koko the Clown, Betty Boop, Popeye and Superman down the hall and under the stairs, literal testaments to persistence of vision? It seems the pressure was too much--and it shows in Richard Fleischer's work, a frantic outpouring of practically every genre of film. First, a selected filmography:

The Narrow Margin (1952)

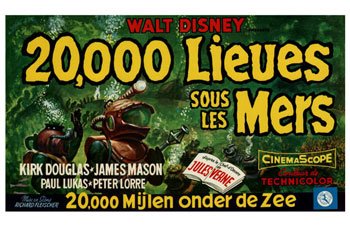

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954)

The Vikings (1958)

Compulsion (1959)

Crack in the Mirror (1960)

Barabbas (1962)

Fantastic Voyage (1966)

Doctor Dolittle (1967)

The Boston Strangler (1968)

Che! (1969)

Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970) (U.S.A. sequences)

Blind Terror, a.k.a. See No Evil (1971)

The New Centurions (1972)

Soylent Green (1973)

The Don Is Dead (1973)

Mr. Majestyk (1974)

Mandingo (1975)

The Jazz Singer (1980)

Amityville 3-D (1983)

Conan the Destroyer (1984)

I've left out a dozen or so, but look at that list, a kind of controlled delirium, marking one of the most enviable directing careers in Hollywood--if the epitome of directing is breadth, almost undiminished relevance, and marketability (especially at the drive-in). Compiling this list from the Internet Movie Database, I was surprised at how many of them I've seen, off and on, since I was kid--I'm old enough to have gone to the theater to see Barabbas--little knowing for years that they were all directed by the same person, a fact that, at least for a few of these titles, I'm finding out just today. Martin Scorsese has commented that a part of him would've loved to have been such a journeyman director, tackling all kinds of pictures, smuggling in a quirk here, a personal vision there, leaving behind a deceptively broad body of work united not just by his name but a half-whispered hint of his inner self, his private world a sly shadow stretching across the films he directed. An auteur of sorts, in other words.

I've left out a dozen or so, but look at that list, a kind of controlled delirium, marking one of the most enviable directing careers in Hollywood--if the epitome of directing is breadth, almost undiminished relevance, and marketability (especially at the drive-in). Compiling this list from the Internet Movie Database, I was surprised at how many of them I've seen, off and on, since I was kid--I'm old enough to have gone to the theater to see Barabbas--little knowing for years that they were all directed by the same person, a fact that, at least for a few of these titles, I'm finding out just today. Martin Scorsese has commented that a part of him would've loved to have been such a journeyman director, tackling all kinds of pictures, smuggling in a quirk here, a personal vision there, leaving behind a deceptively broad body of work united not just by his name but a half-whispered hint of his inner self, his private world a sly shadow stretching across the films he directed. An auteur of sorts, in other words.Richard Fleischer did not seem to have such aspirations--beyond a certain point. He was primarily a maker of entertainments, plugged in to certain exploitation markets, capitalizing on trends. And yet ... Well, I won't push this too far, but in his movies I see two tendencies regularly asserting themselves, one formal, the other thematic.

As a director, he seemed willing to experiment now and again, as long as the movie didn't end up serving the experiment. The hand-held camerawork and claustrophobic spaces of The Narrow Margin; the multiple-role casting of Crack in the Mirror--and the multiple-screen approach of The Boston Strangler--as well as the refusal to make the camera hyperventilate in 10 Rillington Place, despite that film's hysteria-inducing subject matter; even his willingness to ride the '80s 3-D mini-revival: These films and more provide glimpses of someone willing to take chances--not without cause, but in the service of the story. His approach to these stylistic risks is not always virtuosic--except for perhaps The Narrow Margin and The Boston Strangler--but nevertheless always earnest, always adding intriguing visual layers to genre pictures.

As a director, he seemed willing to experiment now and again, as long as the movie didn't end up serving the experiment. The hand-held camerawork and claustrophobic spaces of The Narrow Margin; the multiple-role casting of Crack in the Mirror--and the multiple-screen approach of The Boston Strangler--as well as the refusal to make the camera hyperventilate in 10 Rillington Place, despite that film's hysteria-inducing subject matter; even his willingness to ride the '80s 3-D mini-revival: These films and more provide glimpses of someone willing to take chances--not without cause, but in the service of the story. His approach to these stylistic risks is not always virtuosic--except for perhaps The Narrow Margin and The Boston Strangler--but nevertheless always earnest, always adding intriguing visual layers to genre pictures. At their best, those formal flourishes served his thematic concerns. In many of his pictures he explores the relationship between the powerless and the powerful--and, more important, the shifting of those roles; consider Barabbas, Crack in the Mirror, Compulsion, The Vikings, Blind Terror, 10 Rillington Place, Mandingo, and Mr. Majestyk. Aligned with this are films that deal with code heroes, those who stand apart from the norm to assert their personal moralities, as seen in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, The Narrow Margin, Soylent Green, Che!, and The New Centurions--and OK, even Conan the Destroyer. Finally, and perhaps most telling, are the movies that pry open secretive lives, especially ones that disrupt society's smooth workings with sickening, violent force: Compulsion, The Boston Strangler, and 10 Rillington Place. Again, shifts in power, sick surprises in the dark.

At their best, those formal flourishes served his thematic concerns. In many of his pictures he explores the relationship between the powerless and the powerful--and, more important, the shifting of those roles; consider Barabbas, Crack in the Mirror, Compulsion, The Vikings, Blind Terror, 10 Rillington Place, Mandingo, and Mr. Majestyk. Aligned with this are films that deal with code heroes, those who stand apart from the norm to assert their personal moralities, as seen in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, The Narrow Margin, Soylent Green, Che!, and The New Centurions--and OK, even Conan the Destroyer. Finally, and perhaps most telling, are the movies that pry open secretive lives, especially ones that disrupt society's smooth workings with sickening, violent force: Compulsion, The Boston Strangler, and 10 Rillington Place. Again, shifts in power, sick surprises in the dark.Now, I know that one could extract such trends from the career of any prolific drector, but I keep seeing these tendencies to consider stylistic possibilities and to explore the nature of heroism (sometimes the mere exercise of brute force)--and often to peer at the lurkers in the shadows, those who disrupt all moral codes, public and personal. Again I hear echoes of Scorsese, who also seems obsessed with outsiders and subversives, and who also cannot resist playing with the camera and his casts. I don't know if Hollywood can much sustain Scorsese--and I know as time goes on we will not see many directors with Fleischer's broad resume. I'm happy to have grown up with his films--often catching them at the drive-in, where many of them belong (and of course that is a compliment)--and I urge you to seek out his movies yourself--or rediscover them, lined up one after the other, from the ridiculous to the sublime. Go and Netflix a Richard Fleischer Memorial Film Festival; as you can tell from the titles, you'll at least be guaranteed variety.

No comments:

Post a Comment