"Cut the crap, man, this is Shaft. " All his life, it seems. Gordon Parks took photographs for the Farm Security Administration. While Dorothea Lange snapped migrant farm workers and Walker Evans praised famous men--as Alabama sharecroppers--with James Agee, Gordon Parks turned to Ella Watson, a cleaning-woman in Washington, D.C., where, Parks insisted, "discrimination and bigotry were worse there than any place I had yet seen." His photographs of Watson were more small essays than journalism. Like his fellow FSA photographers, he carefully posed his subjects, choosing from a number of negatives the one worth keeping.

"Cut the crap, man, this is Shaft. " All his life, it seems. Gordon Parks took photographs for the Farm Security Administration. While Dorothea Lange snapped migrant farm workers and Walker Evans praised famous men--as Alabama sharecroppers--with James Agee, Gordon Parks turned to Ella Watson, a cleaning-woman in Washington, D.C., where, Parks insisted, "discrimination and bigotry were worse there than any place I had yet seen." His photographs of Watson were more small essays than journalism. Like his fellow FSA photographers, he carefully posed his subjects, choosing from a number of negatives the one worth keeping.  I was looking at some of his photographs, as well as Lange's and Evans', and thinking about a student presentation I had heard earlier today in a course on media and ethics (and I will not take this solemn occasion to discuss the ironies of the life of the mind). The student felt that the ethical responsibility of the photojournalist was to relate in unflinching detail What Is. He's right, but he's also aware that photographs are not entirely objective moments. The presence of the frame itself imperatively demands subjectivity. The trick--at least as far as the ethics of the situation are concerned--is not to let the frame send the photographer down the slippery slope. As always, the truth slips off to the side, down at the periphery, even while the finger touches and the camera's eye momentarily stares, but the photographer has to keep shooting, getting the truth back in the frame, shot by shot, until it begins to behave. Tough work.

I was looking at some of his photographs, as well as Lange's and Evans', and thinking about a student presentation I had heard earlier today in a course on media and ethics (and I will not take this solemn occasion to discuss the ironies of the life of the mind). The student felt that the ethical responsibility of the photojournalist was to relate in unflinching detail What Is. He's right, but he's also aware that photographs are not entirely objective moments. The presence of the frame itself imperatively demands subjectivity. The trick--at least as far as the ethics of the situation are concerned--is not to let the frame send the photographer down the slippery slope. As always, the truth slips off to the side, down at the periphery, even while the finger touches and the camera's eye momentarily stares, but the photographer has to keep shooting, getting the truth back in the frame, shot by shot, until it begins to behave. Tough work. Parks' photographs reflect this effort. They are studiously flat at times, carefully lit--almost over-lit, as if to implore the camera to tell the truth. In the end, then, they are ethical moments, if only because Ella Watson stares back at me, and the moment is almost, as they say in the interpersonal relations biz, "transactional"--even despite the almost-joke of her American Gothicism. And that is why I trust her, and the photo, and Parks, despite the liberties of composition. I'm willing to accept limits--what else can one do?--as long as I feel that transaction. Reading that Parks had died, I looked at some stills from his film Shaft (1971), and made a tentative connection between Richard Roundtree's serious mouth and honest eyes. I know I may be dreaming, but everywhere I look these days I see entreaty, and feel my own sorry attempts to answer as I should, without artifice; beyond my own unavoidable frame and sometimes-self-conscious pose.

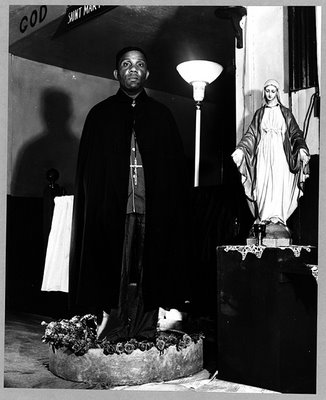

Above: Reverend Gassaway stands in a bowl of sacred water banked with the roses that he blesses and gives to celebrants. Photograph by Gordon Parks, 1942.

Above: Reverend Gassaway stands in a bowl of sacred water banked with the roses that he blesses and gives to celebrants. Photograph by Gordon Parks, 1942.

No comments:

Post a Comment