As I've mentioned before, I continue to be pleased with the great gift I've given myself at this time in my movie life, a kind of second youth: revelatory first viewings of the great ones, the must-sees that I haven't, tugging at my sleeve, reminding me that I have measured out my life in popcorn boxes, and have miles of film to go, and so on. Poetic, but at the heart of it a practical concern: Do I have time for them all?

As I've mentioned before, I continue to be pleased with the great gift I've given myself at this time in my movie life, a kind of second youth: revelatory first viewings of the great ones, the must-sees that I haven't, tugging at my sleeve, reminding me that I have measured out my life in popcorn boxes, and have miles of film to go, and so on. Poetic, but at the heart of it a practical concern: Do I have time for them all? Well, at least one more (he told himself again):

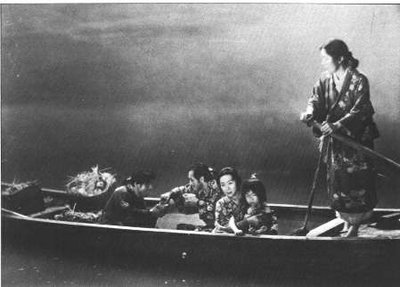

Ugetsu Monogatari (1953) is Kenji Mizoguchi's retelling of Akinari Ueda's "Tales of a Pale and Mysterious Moon After the Rain"--its "informal literal English title," as the Internet Movie Database informs me--and I'll never get tired of those informal literal translations, stiff and beautiful, like the film's ghostly Lady Wakasa (Machiko Kyo), lovely as only an Asian ghost can be, hiding in the woods like a fawn, but still the doom of anyone who gets too close. The film alternates between domestic melodrama and archetypical fable: Two simple but ambitious men--one (a potter) pursues wealth, the other (a would-be samurai), glory--endanger their families during Japan's feudal wars for the sake of their desire for gain, while ghosts possess and spirits soothe, until ambition is humbled beneath the buddhistic yearning for a middle path of compassion amidst suffering.

Ugetsu Monogatari (1953) is Kenji Mizoguchi's retelling of Akinari Ueda's "Tales of a Pale and Mysterious Moon After the Rain"--its "informal literal English title," as the Internet Movie Database informs me--and I'll never get tired of those informal literal translations, stiff and beautiful, like the film's ghostly Lady Wakasa (Machiko Kyo), lovely as only an Asian ghost can be, hiding in the woods like a fawn, but still the doom of anyone who gets too close. The film alternates between domestic melodrama and archetypical fable: Two simple but ambitious men--one (a potter) pursues wealth, the other (a would-be samurai), glory--endanger their families during Japan's feudal wars for the sake of their desire for gain, while ghosts possess and spirits soothe, until ambition is humbled beneath the buddhistic yearning for a middle path of compassion amidst suffering. I just finished teaching a college writing course; I had the students slam and skid like demo-derby drivers into the two-wheeled-turns and fireballs of various Deep Thinkers and High Talkers, from Plato to Emerson, Jung to Lao-Tzu. We finished with the topic of ethics and morality, for which we read a little Torah--decalogue and addenda, Bill Blake's dreaded "thou shalt not's"--and some Sermon on the Mount--in which Jesus, with a straight face (I think Keaton learned it from Him), explains how the Law will stand (except for, you know, all that stoning and scowling and blind adherence)--and a sura from the Koran--ever notice how Allah sounds awe-fully familiar to Judeo-Christian ears, especially in His insistence that we take care of innocents and remember what side our bread's buttered on--or however that goes--I've always had adage dyslexia. We then listened to Iris Murdoch explain why religion is unnecessary for morality, and we even gave glowering, towering Nietzsche a go-round; he was alternately hated and loved by my students. Some were insulted because he called them weak-minded whiners for believing in God (I explained to them that he was not under the same restrictions as they to treat his opposition with respect--as to why that's so, I maintained a diplomatic silence; he was, after all, our guest.); others were relieved to hear that, God being dead, nothing was going to stand in their way, and they could finally be happy.

I just finished teaching a college writing course; I had the students slam and skid like demo-derby drivers into the two-wheeled-turns and fireballs of various Deep Thinkers and High Talkers, from Plato to Emerson, Jung to Lao-Tzu. We finished with the topic of ethics and morality, for which we read a little Torah--decalogue and addenda, Bill Blake's dreaded "thou shalt not's"--and some Sermon on the Mount--in which Jesus, with a straight face (I think Keaton learned it from Him), explains how the Law will stand (except for, you know, all that stoning and scowling and blind adherence)--and a sura from the Koran--ever notice how Allah sounds awe-fully familiar to Judeo-Christian ears, especially in His insistence that we take care of innocents and remember what side our bread's buttered on--or however that goes--I've always had adage dyslexia. We then listened to Iris Murdoch explain why religion is unnecessary for morality, and we even gave glowering, towering Nietzsche a go-round; he was alternately hated and loved by my students. Some were insulted because he called them weak-minded whiners for believing in God (I explained to them that he was not under the same restrictions as they to treat his opposition with respect--as to why that's so, I maintained a diplomatic silence; he was, after all, our guest.); others were relieved to hear that, God being dead, nothing was going to stand in their way, and they could finally be happy.  We finished with the Dalai Lama, who in his own way provided for them the least accessible text. This surprised me at first, since he is non-sectarian and kindly, and a bit of a celebrity. But in the selection we read from Ethics for the New Millennium he begins, "all the world's major religions stress the importance of cultivating love and compassion," which made him lose credibility right off the bat among both believers and non-believers: the former seemed uncomfortable with the way he lumped them together with other camps, and the latter simply knew he was wrong. But that isn't the worst of it. In common-sensical declarative sentences, he announces the need for "unconditional, undifferentiated, and universal" compassion--"empathy" is the word he keeps using, "our ability to enter into and, to some extent, share others' suffering"--and insists that one should engage in this kind of behavior without any thought at all for gain--but that the effect is nonetheless gain; such compassion, he argues, "is the wisest course for fulfilling self-interest."

We finished with the Dalai Lama, who in his own way provided for them the least accessible text. This surprised me at first, since he is non-sectarian and kindly, and a bit of a celebrity. But in the selection we read from Ethics for the New Millennium he begins, "all the world's major religions stress the importance of cultivating love and compassion," which made him lose credibility right off the bat among both believers and non-believers: the former seemed uncomfortable with the way he lumped them together with other camps, and the latter simply knew he was wrong. But that isn't the worst of it. In common-sensical declarative sentences, he announces the need for "unconditional, undifferentiated, and universal" compassion--"empathy" is the word he keeps using, "our ability to enter into and, to some extent, share others' suffering"--and insists that one should engage in this kind of behavior without any thought at all for gain--but that the effect is nonetheless gain; such compassion, he argues, "is the wisest course for fulfilling self-interest." Yeah, right, my students concluded. (Well, at least some of them; the rest were silence, ha ha.) This kind of thing, they admitted, sounds nice--poetic, sensitive, idealistic--but enemies are enemies, after all, and life is competition (and this they know: as students their intellectual worth is measured by a GPA, down to the hundredth of a point), and such idealism is fine for him, and so on. Self-interest and relativism combined to marginalize His Holiness. Earlier, we had read Machiavelli, who knew all about power; if pressed, I think as a group they'd vote him the most useful thinker, more so even than Jefferson with his generalities about equality and Maria Montessori and her advice to let kids fidget. (We read not deeply, but with breadth.) In short, you need to learn how to compete, that is, win; and, as you do, be prepared for attack; these are life's constants.

This is the smoking, rubble-strewn plain upon which Ugetsu begins. The men seek fortune and glory, and are indeed successful, but of course at a bitter price. And it is paid in a dreamlike marketplace, where Genjuro's (Masamuki Yori) babble of commerce is hushed by a beautiful, gliding ghost; and on the battlefield, where the clatter of warfare delivers a general's head to an accidental samurai, Tobei (Eitaro Ozawa). Their gains and losses, captured by Kazuo Miyagawa's mist-shrouded cinematography, provide an illustration of the Dalai Lama's calm insistence that one must enter another's suffering to end one's own--and the other's. Mizoguchi devotes the middle portion of his film to Genjuro's "possession" by Lady Wakasa. She is many things, not the least of which respite from the storms of ambition--as well as its prize: a beautiful, Geisha-like patroness who murmurs love over both Genjuro and his blue-tinged pottery. It is an essay on beauty, love, and delusion. And then Mizoguchi draws us down to the core, as he lingers on the child in the story, Genichi (Ikio Sawamura), and the women who suffer, Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka) and Ohama (Mitsuko Mito), whose fates are mirrored by the tale of Machiko Kyo's Lady Wakasa, abandoned as her noble house fell, lost like Miyagi and fallen like Ohama. Genjuro, seduced by the Lady's ghost, is then soothed by his wife Ohama's spirit, who appears to remind him of his true need--to show compassion and thus be loved--and lays him to rest, back home with his son.

Mizoguchi's film arrived at an opportune time for me. Just as I was watching entreaties for selflessness fail in the classroom, the movies let me watch those pleas reassert and fulfill their promises. I'm glad I waited for Ugetsu--or maybe it was waiting for me, when I needed it. George Harrison is right: all things must pass. Ugetsu documents how one thing, in passing, leads to another, which passes too, but not before meeting yet another, in a space where, as the Dalai Lama tried to tell my students, one can assert, "there is nothing amazing about being highly educated; there is nothing amazing about being rich. Only when the individual has a warm heart do these attributes become worthwhile." Sneer at such beatitudes if you must; all it adds up to is perfection.

Mizoguchi's film arrived at an opportune time for me. Just as I was watching entreaties for selflessness fail in the classroom, the movies let me watch those pleas reassert and fulfill their promises. I'm glad I waited for Ugetsu--or maybe it was waiting for me, when I needed it. George Harrison is right: all things must pass. Ugetsu documents how one thing, in passing, leads to another, which passes too, but not before meeting yet another, in a space where, as the Dalai Lama tried to tell my students, one can assert, "there is nothing amazing about being highly educated; there is nothing amazing about being rich. Only when the individual has a warm heart do these attributes become worthwhile." Sneer at such beatitudes if you must; all it adds up to is perfection.

No comments:

Post a Comment