Let me get a piece of business out of the way: Daniel-Day Lewis was robbed. He should've received an Oscar nomination for The Ballad of Jack and Rose. A nascent thesis stirring fitfully in my head asserts that Day-Lewis' Jack cut too close to home for the Academy rank n file. Just consider the weird idealism of Jack's frozen-in-time commune politics, placing him squarely in militant favor of wetlands; but his passion forces him into isolation, a self-described "experiment" that, by the end of the film, in turn forces him to identify with his land-developer nemesis (played as a perfectly bland, straightforward capitalist by the always-welcome Beau Bridges); Jack despairingly considers the possibility that both of them are the same: eager to do whatever they please. Add to this Jack's fever-dream approach to his needs--he's dying of cancer--and the enlistment of his mainland four-months' lover, Kathleen (Catherine Keener, playing regular folk--and getting it right once again), who arrives with her own varied levels of dysfunction in her separate-fathers children. Finally, and near-tragically, there's his appalling misreading of the needs of his daughter (Camilla Belle, who keeps up with Day-Lewis, and adds her own inscrutable colors of sunshine and fire). All of this in a general air of meltdown as Jack rails against upper-class land-consumerism in an almost literally fabulous landscape that is neither campy enough to toy with its out-of-step hippie possibilities or cozy enough to make the Academy feel good about their wagons-in-a-circle intentions--and their own land-consumerism, their own denial of a once-embraced counter-culture. And there's yet another rub: Did they ever embrace it, or merely co-opt it? Just check out the current nominations if you think I'm being reactionary. Let's be honest: Would Nicholson have won today for Randall Patrick McMurphy, or Peter Finch for Howard Beale, or De Niro for Jake LaMotta? Maybe I'm stretching it, but it seems these days the Academy is using the nominations to compensate for lost political turf.

But I digress, because I really really liked The Ballad of Jack and Rose.

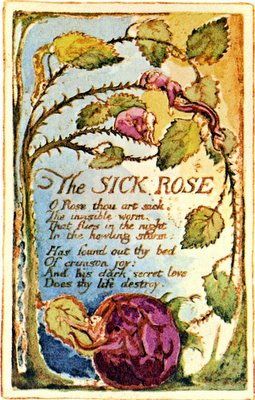

This is a movie with many mansions: Shakespeare, the Book of Genesis, Sarah Orne Jewett's tale of innocence tempted, "A White Heron," Samson's tonsorial agonistes, even the attempts at salvation through wrath in Sling Blade and the loss of communality in Sunshine State. But one moment in particular resonated so deeply and surely, I actually paused the DVD to recite a poem to my ever-patient wife. Jack lives on land he had started as a commune like a postmodern Prospero--he's an engineer--on "an island off the east coast of the United States" with his daughter, Rose-as-Miranda, while the roles of Caliban and Ferdinand are blended into various males who visit the island and pose alternatives, some threatening, others inviting. In retreat from the encroaching "naughty world," Jack and Rose grow close, to indulge in a gross understatement. At a moment of loss and betrayal, and of subsequent reunion and reconciliation, father and daughter embrace, pause, kiss--and break in confusion and shame, as Jack realizes how deeply he has damaged both of them, how dangerous their relationship has become. He wanders into sleep, and we get a shot of a caterpillar settling onto a leaf, preparing to feast. He bolts awake, momentarily re-living the kiss aborted, and William Blake whispered in my ear with the clarity of a well-meaning madman:

Jack is forced to see himself as the one with a dark secret love--and it is not incest, but the love of self--but before I frown too deeply, I am reminded of his cancer, and the cold sweat that pours out of him, and--but no spoilers here. Watch this remarkable film of archetypical potency, its howling storm, its crimson joy. How I love to steal from the best--and to see the best illuminated, if I may use a Blakean term, by the images of this film.

I regret to admit that perhaps the director-writer, Rebecca Miller, found a deeper well of myth and fable than Terry Gilliam did in The Brothers Grimm. I will not dwell on unflattering comparisons; suffice it to say that Miller lifts the dipper and has us drink deeply. Her movie slams around and pitches fits, and whispers and hints, and searches for whatever light the dark night can spare.

No comments:

Post a Comment