For the past few days I've been thinking about the lure of The Story, while leaning as always toward the lifting wind of The Image; and here we come to Terry Gilliam's The Brothers Grimm, which posits Jacob (Matt Damon) and Wilhelm (Heath Ledger) as con-artist-ghostbusters, a la Michael J. Fox's Frank Bannister in the Robert Zemeckis-produced The Frighteners (1996), directed by Peter Jackson (and there's something to consider for another day); except Gilliam's brothers have no supernatural entities, like Bannister's ghosts, as confederates. No, they're special effects experts, with all-too-human stooges that they dress up and fling about in staged re-creations of frightened villagers' tales, vanquishing the flashpot apparitions, revenants, and poltergeists, and thus cementing their reputation as Olde Deutschland's premier exorcists. Except Jacob believes The Truth Is Out There, and scribbles every tale the villagers relate, building the famous anthology one rube at a time--with himself as the most gullible: The film begins with the brothers as children; little Jake has been sent out to get medicine for his deathly ill little sister, and comes back with magic beans. It is a black beginning. And of course eventually they run into actual supernaturals, minions of a genuine fairy-tale curse that manages to combine most of the stories we associate with the brothers, from the Big Bad Wolf to Sleeping Beauty, not to mention a magic axe that works like a lethal boomerang and moving trees that would spook an Ent. Along the way, Jacob falls in love and Wilhelm learns to embrace the power of a tale told so well it becomes the truth. And at every moment Gilliam is given the opportunity to let his untrammeled imagination romp up and down and all around the fx/digital funpark.

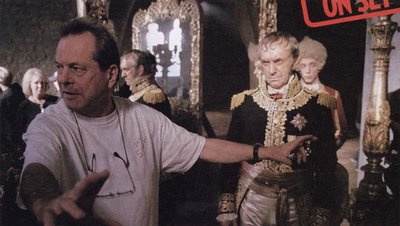

So why is The Brothers Grimm not a better movie? I've read about the pre-production troubles--makeup, casting, and the big one: Bob Weinstein firing Gilliam's director of photography, Nicola Pecorini. And, as usual, he didn't get the budget he wanted. But I'm looking at the finished product--I have no idea, for instance, what Pecorini's movie would have looked like, and I believe Matt Damon's nose was supposed to be bigger or something--and it seems to move in fits and starts, and wanders a bit in tone, and sometimes fails to make smooth transitions from scene to scene, and--hold on; I'm describing most Terry Gilliam movies, for which I have inordinate fondness, from Holy Grail (1975) to Time Bandits (1981), and on to the heyday--hey-decade?--of Brazil (1985), The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988), The Fisher King (1991) and Twelve Monkeys (1995). Each of these has its attendant tales of woe, culminating in his implosion in 2000 with the ill-fated, never-completed The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, in which everything, including weather that was Biblical in its wrath, conspired against him. And yet the other pictures were made, and I can watch them over and over, any old time.

So why is The Brothers Grimm not a better movie? I've read about the pre-production troubles--makeup, casting, and the big one: Bob Weinstein firing Gilliam's director of photography, Nicola Pecorini. And, as usual, he didn't get the budget he wanted. But I'm looking at the finished product--I have no idea, for instance, what Pecorini's movie would have looked like, and I believe Matt Damon's nose was supposed to be bigger or something--and it seems to move in fits and starts, and wanders a bit in tone, and sometimes fails to make smooth transitions from scene to scene, and--hold on; I'm describing most Terry Gilliam movies, for which I have inordinate fondness, from Holy Grail (1975) to Time Bandits (1981), and on to the heyday--hey-decade?--of Brazil (1985), The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988), The Fisher King (1991) and Twelve Monkeys (1995). Each of these has its attendant tales of woe, culminating in his implosion in 2000 with the ill-fated, never-completed The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, in which everything, including weather that was Biblical in its wrath, conspired against him. And yet the other pictures were made, and I can watch them over and over, any old time.Maybe someday I can say the same for Grimm. For now, I feel a little woozy. The sound and fury didn't even seem to want to signify, although it was prime Gilliam territory: the nature of storytelling, the blurry line between what happens and what we tell ourselves and others--and how that confusion is a magic feeling, a kind of innocent freedom that we can breathe in deeply, like Bruce Willis sticking his head out the car window in pre-Apocalypse Philadelphia in Twelve Monkeys, grinning like blissed-out fools because Terry told us we could. At least that's how Grimm felt all over its surface--and down to the roots in selected moments: the little girl with the red hood picking her way through the trees, the giddy feeling of height in the Rapunzel-esque tower, glimpses of the forest that felt like Tolkien. (After seeing Holy Grail, I was convinced someone could do a live-action LOTR; we may be better off that Jackson did it, but Gilliam helped set the standard.) But in terms of the picture's Big Picture, I don't think Gilliam's heart was all the way in it,as in Munchausen and Fisher King, flawed themselves, but shimmering and vibrating with the internal light of deeply personal work. With Grimm, I did not see that light.

But, but, but. Maybe I'm wrong; maybe, like Brazil, a movie I admire greatly, Grimm is more like Gilliam than I want to admit, more like the reckless animator who started off with snippets and sketches, split-second bits and sarcastic asides and mutterings. I will say just about every piece of Grimm is worth it; I'm just not sure it holds together. Again, though, if one is to side with Gilliam, this may be a necessary condition. I am reminded of the map of the universe in Time Bandits: It's irresistible only because it's full of holes.

But, but, but. Maybe I'm wrong; maybe, like Brazil, a movie I admire greatly, Grimm is more like Gilliam than I want to admit, more like the reckless animator who started off with snippets and sketches, split-second bits and sarcastic asides and mutterings. I will say just about every piece of Grimm is worth it; I'm just not sure it holds together. Again, though, if one is to side with Gilliam, this may be a necessary condition. I am reminded of the map of the universe in Time Bandits: It's irresistible only because it's full of holes.

No comments:

Post a Comment