Today I continue, like some dope who's never watched a movie in his life, to be in a frame of mind where all of a sudden I'm being captivated by actual plots. As any Constant Reader is painfully, deadeningly aware, I'm usually dedicated to the Mystic Order of the Seeing Eye, whose members worship the power of a film's visual elements to do most of the work of conveyance. Light, shadow, camera position and movement, shot juxtaposition--the manipulation of images draws me in, and often to a place the film may not intend; a Rorschach effect leads me to my own conclusions about a movie, in a dream-logic that changes everything. The movie, then, becomes the clean slate on which I write--or scrawl, or doodle; I'm not always as clever as I think, nor as deep-minded as I should be--until the film becomes a malleable substance, like either gold or Silly Putty, depending, not exactly on the movie itself, but my effort.

But as I've been saying, recently I've been taken in by moving parts, so to speak: stories with structure and substructure, seductive mechanisms--oh all right: dream machines. Blech. Nonetheless, a few days after Fear and Trembling I watched You Can Count on Me (2000), and although Kenneth Lonergan's debut film has a few sags and creaks, it's smart enough to depend almost entirely on the characters to do their old thing: They act, which defines them, and interact, which defines their relationships. Simple stuff, but Laura Linney, Mark Ruffalo, Rory Culkin, Mathew Broderick, even Lonergan himself (as Linney's parish priest, whose deadpan refusal to summon any satisfying outrage at her indiscretions is both funny and affecting--and effective, in a moral-instruction-cum-passive resistance way), all plug away to make us see their characters clearly so that we can follow their story with sympathy, affection--and, best of all, crossed fingers. Lonergan and his cast make us wish them the best, even though his story refuses to neatly fold and stack them like dirty laundry finally transformed into Downy-soft linen.

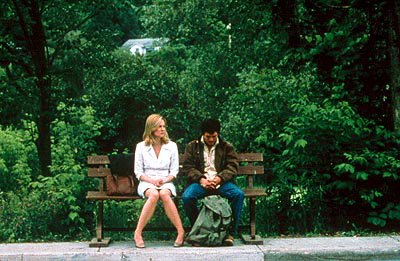

But as I've been saying, recently I've been taken in by moving parts, so to speak: stories with structure and substructure, seductive mechanisms--oh all right: dream machines. Blech. Nonetheless, a few days after Fear and Trembling I watched You Can Count on Me (2000), and although Kenneth Lonergan's debut film has a few sags and creaks, it's smart enough to depend almost entirely on the characters to do their old thing: They act, which defines them, and interact, which defines their relationships. Simple stuff, but Laura Linney, Mark Ruffalo, Rory Culkin, Mathew Broderick, even Lonergan himself (as Linney's parish priest, whose deadpan refusal to summon any satisfying outrage at her indiscretions is both funny and affecting--and effective, in a moral-instruction-cum-passive resistance way), all plug away to make us see their characters clearly so that we can follow their story with sympathy, affection--and, best of all, crossed fingers. Lonergan and his cast make us wish them the best, even though his story refuses to neatly fold and stack them like dirty laundry finally transformed into Downy-soft linen.  The prizes go all around here: Linney's Sammy Prescott is feeling the pressure of being The Rock, the one who stayed in the small-town house, despite her parents' death when she and her brother were small and her own separation from her son's father. Sammy is keeping-it-together, and it is painful to watch--until her classic ne'er-do-well brother Terry comes home, at first just for money, but then for more: Ruffalo gives Terry such a lonely heart--and so much of it--that it threatens to become Uncle Buck-ish--and the fact that Terry embarks on an older-brotherly relationship with Sammy's little boy, played by a Culkin, no less, doesn't help the almost-uncomfortable movie echo. But Ruffalo and Culkin and the script pull back from the sloppy stuff, and everyone, even Matthew Broderick's insecure-martinet bank manager, Sammy's new boss, draws us into the story with neither sledgehammers nor violins.

The prizes go all around here: Linney's Sammy Prescott is feeling the pressure of being The Rock, the one who stayed in the small-town house, despite her parents' death when she and her brother were small and her own separation from her son's father. Sammy is keeping-it-together, and it is painful to watch--until her classic ne'er-do-well brother Terry comes home, at first just for money, but then for more: Ruffalo gives Terry such a lonely heart--and so much of it--that it threatens to become Uncle Buck-ish--and the fact that Terry embarks on an older-brotherly relationship with Sammy's little boy, played by a Culkin, no less, doesn't help the almost-uncomfortable movie echo. But Ruffalo and Culkin and the script pull back from the sloppy stuff, and everyone, even Matthew Broderick's insecure-martinet bank manager, Sammy's new boss, draws us into the story with neither sledgehammers nor violins. My lasting impression is that everyone manages to involve us in the way they see their situation. We are allowed to cruise around in everyone's perspective--and not with the subliminal seductions of editing and cinematography, but because the story demands we do so. While not the most tightly plotted picture, it gets closer to the kind of storytelling that eschews visual aids so that we can savor conversation and resolution. This, again, is essentially a narrative experience, albeit fueled by the eminently watchable tics and graces of the characters. And while Lonergan does not give me the denouement I desired, in my silly sentimental way, it was the one that made sense.

More or less. My twelve-year-old son saw the key signs that things were going south for these characters, people he had grown attached to, admired, laughed with, shook his head ruefully over, and so on, so he bailed out with about twenty minutes to go. He also did this with Treasure of the Sierra Madre when Bogart died; despite my entreaties, my son cuts the Gordian knot occasionally, re-writing certain movies in the act of refusing to endure the thwarted promises of the first two acts. Walking out before the sad ending; now that's editing.

No comments:

Post a Comment