Francois Truffaut made one English-language movie,

Fahrenheit 451 (1966). It was the first Truffaut movie I ever saw; I was probably starting high school, not so much interested in Truffaut--but I was reading Bradbury without check. I didn't pay attention to Truffaut until 1973, with

La Nuite americaine (

Day for Night), and by then I was turning into a cinephile of all-but-academic aspirations (for better or worse, although I couldn't dream of going to college and majoring in movies--Who would have thought such a thing?--but I did know that I had to take movies seriously, bound as they were to every aspect of my waking and dreaming lives), so seeing Truffaut films was akin to eating one's vegetables--although that's not entirely fair, since, although they were good for me, they were also pretty tasty. Again, though, around 1970, when I think I saw

Fahrenheit 451 on TV, it was all about my favorite fabulist, Mr. Dark, the presser of dandelions, the Illustrated Man, the Emperor of the October Country--sorry, but I could go on; my abiding affection for Bradbury remains, past all better judgment. After all, when I was a kid he compelled me to read, more than Seuss, more than DC or Marvel Comics, even more than my accidental forays into the classics of an earlier, Anglo-Saxon generation, with

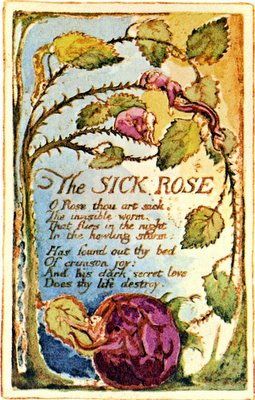

Alice, both in Wonderland and through the looking-glass, and Kipling's

Just-So Stories, and even a big, woodcut-illustrated, slightly creepy edition of

Jane Eyre. With Bradbury, though, one can feel the arrested development--in the best possible way--in his insistence on jarring images, wildly veering plots--or short stories like dreams--I almost wrote "Bradburian dreams," which should just about sum up his iron hold--his ability to thrust at the reader a startlingly apt metaphor--still potent: my wife read

Dandelion Wine after we had a son, and she approved without reflection Bradbury's comparison of boys in kitchens to bees around a hive--the exuberant hunger, the circling joy. I have always read Bradbury with an open eye, glad to be rid of guile and order.

But

Fahrenheit 451 is an odd corner for Bradbury. Yes, there are hints of dystopic futures in a number of his short stories; but those often feel less like polemics than meditations on loneliness and isolation, sad lingering at 3:00 AM, his favorite time, when everything is at once dark and all-too-clear. In his novels, these become moments and moods--the father, up late and ruminating, in

Something Wicked This Way Comes or the rising black of the ravine in

Dandelion Wine. I'm not sure, but his short science fiction--and with Bradbury, the word "science" must be used gingerly, like a busted apple-corer-peeler; somebody could get hurt--does not seem to live in the same world as

Fahrenheit 451. I sometimes think of the novel as his rueful hit, the one thing everyone knows him for, but which does not speak to his true self. This happens all the time: Imagine if the

William Tell Overture, as much slam-bang fun as it is, were all people knew of you. Sure, you get invited to all the bashes, and it's played in the marketplace, but what about all those other peerless passages? So it is with Bradbury's

Fahrenheit 451.

And with Truffaut's version, except in reverse: Many people who like movies in general do not know Truffaut's work in particular, perhaps except for

Fahrenheit 451--often discovered because they love Bradbury, or at least know of his book, and thus run into Truffaut accidentally, and in some ways at the weirdest place: this oddly set, slightly distracted movie, a future signaled only by big (for 1966) TVs and a monorail, a stark comic book without exclamations. One of my daughters saw it in her high school English class; she loves movies, but was unimpressed by this one. It is all-but-forgotten; I'm sure younger cinephiles like herself will have much more fun with

The 400 Blows or

Jules et Jim. My own memory of the film is that I simply enjoyed seeing Bradbury on the screen, and was moved by the snowy scenes of the Book People at the end, reciting, becoming--well, allowing at least a part of themselves to become--the one book they've memorized. I think that no matter who films the book, that is the one ineluctable Bradburian moment, the one that cannot be denied, no matter what motives draws a filmmaker to the book. (Mel Gibson was supposed to direct and star in a remake; now it appears Frank (

Shawshank Redemption) Darabont is making a pass at it. I suspect that ending will again emerge intact.)

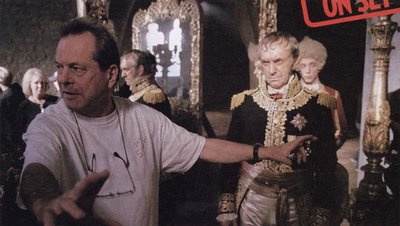

With Truffaut, his motives do not always seem clear. What is most consistent is the movie's pervasive lethargy. Yes, there are some jolts: the dual casting of Julie Christie as both Montag's wife and his "muse," and Nicholas Roeg's black-on-white-on-RED! cinematography, and some sudden outbursts, both verbal and physical, and the occasional abrupt scene shift--but, more than Bradbury's anxiety over a post-literate video world (and you know he's right), Truffaut seems to focus on the pharmaceuticals and bullying that permeate his version. The effect is of a slow descent punctuated by snarls. Linda Montag pops pills and sinks into the interactive, self-esteem-boosting TV world, where lessons in jiujitsu combine with banalities--and she uses both in her marriage, at one point tumbling Guy (Oskar Werner) into bed with a smoothly executed trip-and-takedown, and elsewhere eager to have her life placidly mirror the congratulatory commonplaces of her favorite interactive program. Montag's superior, "The Captain" (Cyril Cusack) seems a confident professional, a self-contained old-campaigner-turned-bureaucrat--but we see him quick to berate a young man on the street, slapping at him, hectoring like--well, like most of the adults in this film: at one point we view a news broadcast about a crackdown on young men with long hair, shorn in the streets by jubilant officers.

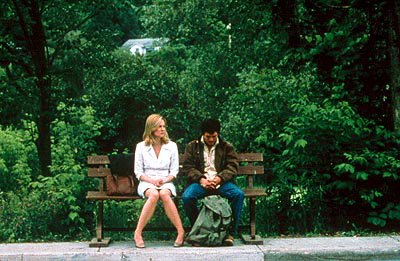

And watching this movie after many years, such scenes made me realize how much this movie depended on the fact that it was made in 1966. Truffaut had latched onto the drugged-out-middle-class trope, fried in the living room, hating the hippies--and the intellectuals, the, ah, bookish. Not the world Bradbury saw, exactly--but close; the book first appeared in 1953, not a good time to be a pinko or a Beat--or a self-proclaimed constant child; consider the famous story about Bradbury and special effects master Ray Harryhausen, promising each other in their youth to never grow up. More Pan than Yippie. Still, Truffaut sees the world Montag flees to, that of the woodland Book People, as a sweet, inter-generational counter-culture that wishes solitude and the bliss of a good book.

Wait a minute; we seem to be getting back to Bradbury here, the innocent, hopeful smile, the effect of melancholy, the Emersonian love of bare trees and snowfall. Again, I think at the end of the film Truffaut is drawn almost against his will back to the book itself, and its Bradburian confidence in and yearning for the small town, the sublimity of a front porch--actually mentioned in the film, when Montag sees a rocking chair for the first time--and the brave guilelessness of his urge to be "poetic"--which for Bradbury means a kind of vibrating sympathy for the little things, ecstatically making Whitmanesque mountains out of the molehills of the everyday. Both Truffaut and Bradbury seem to work together at the film's end to convey that fear of the losses of 3:00 AM and that affection for the simple sight of someone happily reading, the brisk joy if it, like the snow Truffaut walks the Book People through. Despite his seeming attraction to the youth/freedom-denied elements of the book, Truffaut manages to play notes that are more ephemeral--that is, less political--and more optimistic--that is, less realistic (reading in the snow seems hard work)--to settle like Bradbury's beloved Autumn leaves onto his film's shoulders.