I know how often I watch horror movies: too often. And I know how much I like them: too much. I had a conversation with a friend recently; he said he thinks horror films are immoral. Of course, I didn't pursue his comment, because I was too busy correcting it. I referred to Stephen King, who writes somewhere or other--in Danse Macabre?--that horror is actually the most moral type of fiction. As I remember it, his argument is that in horror the reader/viewer/listener is asked to consider individuals in peril, thus triggering sympathy and anxiety. The fact that you yell at the screen and tell those morons not to go into the cabin--or out into the woods, depending--proves that you have a sense of right and wrong. Even your disgust at how dumb the victims are is a sign of your moral sense at work: You get angry at them, not just because they're stupid--that's just you casting stones--but because you know deep down you'd do the same, and share in their doom. It's a slapdash approach to the evocation of fear and pity, but still pretty potent.

But how often is too often? How much is too much? There's a song by the Cramps--the original horrorbilly punks--called "How Far Can Too Far Go?" If you know Lux Interior, Poison Ivy and company at all, you know their answer: never far enough. The Cramps' catalogue is a What's What of exploitation trash culture, a fun-lovin heinous hootenanny that's the musical equivalent of an Elvis movie produced by William Castle and directed by Doris Wishman. (If you're lost, go to the Internet Movie Database. I can't do everything for you.) I must admit I'm a big fan, mostly because I can see the grin beneath the grimace. The Cramps generate all the moral dread of a Booster Club Halloween Haunted House, despite their misogynistic excess and Ride with the Devil glee.

But how often is too often? How much is too much? There's a song by the Cramps--the original horrorbilly punks--called "How Far Can Too Far Go?" If you know Lux Interior, Poison Ivy and company at all, you know their answer: never far enough. The Cramps' catalogue is a What's What of exploitation trash culture, a fun-lovin heinous hootenanny that's the musical equivalent of an Elvis movie produced by William Castle and directed by Doris Wishman. (If you're lost, go to the Internet Movie Database. I can't do everything for you.) I must admit I'm a big fan, mostly because I can see the grin beneath the grimace. The Cramps generate all the moral dread of a Booster Club Halloween Haunted House, despite their misogynistic excess and Ride with the Devil glee. Real evil, on the other hand, is not nearly as entertaining. You know it well: It plods along beside you, rolling that snowball that gets bigger every inch, the cold work of isolation, egoism, fear, and pride. Death isn't evil; it's just the messenger of your fears. And evil isn't monumental--although give someone enough toothpicks and she'll build you the Great Pyramid. I'm afraid, not because I have anything to fear, but because I don't know enough not to be afraid. So evil in movies is often like a Cramps song: a whisper of the scream, shadows playing along an expressionist corridor. I can deal with that.

But I sometimes get tired of horror movies. I watched I Drink Your Blood (1970), and glanced at some of the DVD extras. There was poor old David E. Durston, the director, still wearily muttering "Roll 'em" like Sisyphus with his rock. And his misery loved company: He trotted out three of the movie's stars, their faces polite, their balding heads--or assertively dyed coifs--like dimming torches, as they sat awkwardly on patio furniture to be mercilessly videotaped. There was some good will, but mostly it all seemed more horrifying than the movie, rabid hippies and all. The movie itself wasn't all that bad, in a Mystery Science Theater kind of way, but as I went from one scene to another, one DVD "special feature" to the next, I began to realize something I'm sure at least some of my friends and Humble Readers must be all too well aware of: One can waste too much time with this junk. The more I watch, the more I feel the weight of that rock.

Like Sisyphus, though, I still go at it. In his famous essay on the myth, Albert Camus writes that he is not interested in what Sisyphus is thinking as he pushes the rock up the hill, but in the moment when he once more confronts the rock:

Like Sisyphus, though, I still go at it. In his famous essay on the myth, Albert Camus writes that he is not interested in what Sisyphus is thinking as he pushes the rock up the hill, but in the moment when he once more confronts the rock:"It is during that return, that pause, that Sisyphus interests me. A face that toils so close to stones is already stone itself! I see that man going back down with a heavy yet measured step toward the torment of which he will never know the end. That hour like a breathing-space which returns as surely as his suffering, that is the hour of consciousness. At each of those moments when he leaves the heights and gradually sinks toward the lairs of the gods, he is superior to his fate. He is stronger than his rock."

I have to confess, sometimes I feel like this when I watch a bad horror movie, which in part is why I watch them: because the feeling is expended on an inconsequentiality, a stupid movie. It is a vacation from the real rock, the need for real strength. I have always been torn between faith and absurdity. I hold them in my hands, like roses and snakes, and sometimes I cannot tell if I'm feeling thorns or fangs. But I always try at the end of the day to live in love, if not with meaning--unless love is enough. I think I am wrestling it into a moral perspective--or wrestling in a moral universe, I sometimes can't tell. But I find Camus' essay irresistible, as I do the Beatitudes, because they both are born from sorrow, pity, and the need for strength. And when I watch yet another bad horror film, I can take a vacation from that need and let some other poor sap get flattened by the monster.

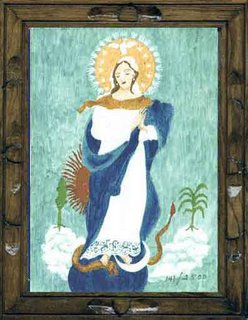

Have you ever seen an image of Mary, the Immaculate Conception? Her dainty foot treads on a snake.

Have you ever seen an image of Mary, the Immaculate Conception? Her dainty foot treads on a snake.

No comments:

Post a Comment