The mystical-psychological-surrealistical-comical-tragical filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky is one of those freakout cool cats of the old school who can say things like, "I ask of cinema what most North Americans ask of psychedelic drugs"; or, better yet, "The apocalypse is now! Americans know this, that the only hope is the flying saucers. Do you know how I see the world? Like a person who is dying. It's a worm who is dying to make a butterfly." Standing all on their lonesome like this, naked and exposed, such utterances seem, to put it mildly, screwy babblings. But the house has many mansions, and it would be a grave error to exclude Jodorowsky. Like David Lynch--and others; let's never forget the mad puppeteer of Prague, Jan Svankmajer--Jodorowsky has always insisted on an alchemical view of things, which means that he can be always be found scooping up dross by the fistful in anticipation of the day when it all turns gold. Hence the world as a worm, the idea of film as a drug: the center of the experience of making--and watching--films is transformation. And for the surrealists, it is a moment's work, a transubstantiation jumpcut. Don't blink or you'll stay a worm.

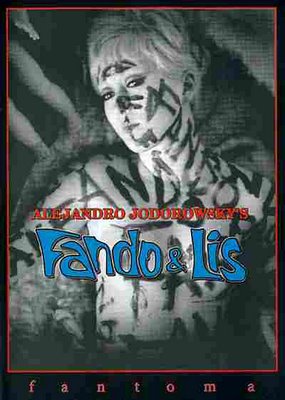

In 1968 he released Fando and Lis, a quest fable about a man and woman who seek the mystical city of Tar. The movie sprung directly, like Zeus' children, from his involvement in surrealist theater in Mexico: it is a filmed "memory" of a Francisco Arrabal play Jodorowsky had directed for the "Theater of Panic" (with an emphasis, I think, on "Pan"). He worked without a script, on weekends--like Night of the Living Dead, also released in 1968; so there: now stop asking whether the universe has meaning--and perhaps on drugs himself. It is a giddy, glorious mess about which I won't go into details, save two.

(1) Lis is unable to walk; we see this idea of disability, sometimes to the point of amputation, in other Jodorowsky characters--most notably for me in Santa Sangre (1989), in which an armless woman essentially enslaves her son, who stands behind her and acts as surrogate hands; this is the only other of his films I've seen. ( And I suppose that's a problem, since that excludes from my discussion El Topo (1970), which many seem to regard as his most extreme film; does that make it a masterpiece?) She is sometimes pushed along in a cart by Fando, but he also often carries her in a strange manner: he holds her horizontally behind him, like an oblong bundle, his arms crooked around her to keep her pressed against his back. It seems the least efficient way of carrying her, but Fando manages to bear the burden for long stretches, sometimes in surprisingly lengthy uninterrupted shots.

(1) Lis is unable to walk; we see this idea of disability, sometimes to the point of amputation, in other Jodorowsky characters--most notably for me in Santa Sangre (1989), in which an armless woman essentially enslaves her son, who stands behind her and acts as surrogate hands; this is the only other of his films I've seen. ( And I suppose that's a problem, since that excludes from my discussion El Topo (1970), which many seem to regard as his most extreme film; does that make it a masterpiece?) She is sometimes pushed along in a cart by Fando, but he also often carries her in a strange manner: he holds her horizontally behind him, like an oblong bundle, his arms crooked around her to keep her pressed against his back. It seems the least efficient way of carrying her, but Fando manages to bear the burden for long stretches, sometimes in surprisingly lengthy uninterrupted shots.(2) Early in their travels, they come upon a devastated city--according to the DVD commentary by Jodorowsky, actually the site of a lunatic asylum that had been demolished. I want this to be the truth; it suppports my orderly universe theory. Amid the rubble, well-dressed people listen to a jazz combo, dance, play blind man's bluff. The central image of this episode is a man playing an upright piano that is on fire. Jodorowsky said it was his homage to Bunuel--and by the way, I'll be watching his film L'Age d'or (1930) tomorrow or Saturday; this is a pretty dizzying week for Your Humble Viewer--but as I watched, another image sprang to mind: In his concert film Big Time (1988), Tom Waits begins a song in closeup, holding upright a thin pole of some sort. The camera slowly recedes, until we realize he is holding onto an umbrella--which is on fire. He continues to sing, while the flames and smoke rise.

While the movie Jodorowsky made is sometimes a bit silly--like the man himself, from what I saw on the DVD extras--I found Fando and Lis compelling, just as I find Jodorowsky indispensable. Elements of surrealism have always peeked from the dark corners of art, from the masks and robes of Greek tragedy to the keening yelps of Japanese theater, from the cautionary grotesques of Bosch's paintings to the dancing bananas of Busby Berkeley's MGM musicals. Panic, indeed: Watching Fando and Lis is like witnessing Pan-rites: goofy but mythopoetic, pretentious but archetypical. Again, there's a line that stretches from the hidden rites of alchemy to Mullholland Drive (2001), and I think we break that line at our peril, because Jodorowsky's right: the world is a worm, but the butterfly is immanent; and when we let it slip away, the surrealists rush up with card tricks and fireworks, and rouse us to attention with stupefying non sequiturs.

While the movie Jodorowsky made is sometimes a bit silly--like the man himself, from what I saw on the DVD extras--I found Fando and Lis compelling, just as I find Jodorowsky indispensable. Elements of surrealism have always peeked from the dark corners of art, from the masks and robes of Greek tragedy to the keening yelps of Japanese theater, from the cautionary grotesques of Bosch's paintings to the dancing bananas of Busby Berkeley's MGM musicals. Panic, indeed: Watching Fando and Lis is like witnessing Pan-rites: goofy but mythopoetic, pretentious but archetypical. Again, there's a line that stretches from the hidden rites of alchemy to Mullholland Drive (2001), and I think we break that line at our peril, because Jodorowsky's right: the world is a worm, but the butterfly is immanent; and when we let it slip away, the surrealists rush up with card tricks and fireworks, and rouse us to attention with stupefying non sequiturs.

No comments:

Post a Comment