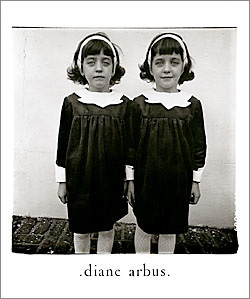

My earliest exposure to "art" photography was Diane Arbus--and it was an uneasy entree. While I was attracted to the images, I was uncertain I should be "enjoying" them. Unlike a painter or sculptor, she had not transformed her subjects, paint and stone inevitably turning them into metaphors, no matter how thinly disguised. No, photography is appropriation. It seems too ready to objectify its subjects, allowing us to maintain a distance that can be cool or cruel, impassive or condescending. The more I looked at her photos, the more I felt I should look away.

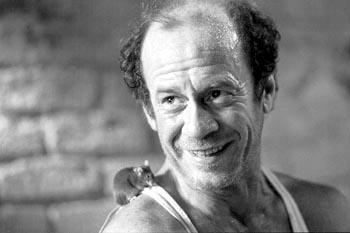

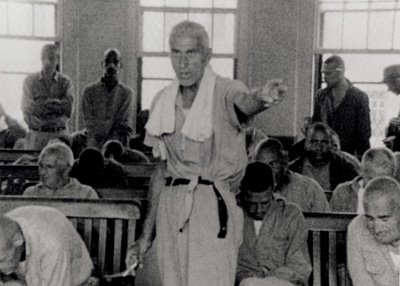

My earliest exposure to "art" photography was Diane Arbus--and it was an uneasy entree. While I was attracted to the images, I was uncertain I should be "enjoying" them. Unlike a painter or sculptor, she had not transformed her subjects, paint and stone inevitably turning them into metaphors, no matter how thinly disguised. No, photography is appropriation. It seems too ready to objectify its subjects, allowing us to maintain a distance that can be cool or cruel, impassive or condescending. The more I looked at her photos, the more I felt I should look away. I have never lost that discomfort around photographs--although I admit I fall into the trap myself, snatching web images of real people to decorate my home-made CD covers--or this blog (as I'm doing right now). My innocent intentions, or outright affection for these images, I fear may not be enough to justify the theft. Documentary films developed this same slightly nauseating tilt in my head, especially the cinema verite work of someone like Frederick Wiseman, whose monumental Titicut Follies (1967), about a Massachusetts institution for the criminally insane, I haven't seen in many years, but still flops meatily around in my head, rising up to stare back at me like old Nietzsche's abyss. This is a movie you cannot even see anymore; the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled it an invasion of the inmates' privacy, despite the fact it had already been filmed--and after the filmmakers were sued by the Commonwealth; maybe it was the Commonwealth's privacy that was invaded. (Where oh where did I see this, then? I'll bet it was on good old PBS, during the glory days of the 1970s, when it seemed devoted to film, from everywhere, about everything.) How's that for a living metaphor about the conflict between those who photograph, that which is photographed, and those who see?

I have never lost that discomfort around photographs--although I admit I fall into the trap myself, snatching web images of real people to decorate my home-made CD covers--or this blog (as I'm doing right now). My innocent intentions, or outright affection for these images, I fear may not be enough to justify the theft. Documentary films developed this same slightly nauseating tilt in my head, especially the cinema verite work of someone like Frederick Wiseman, whose monumental Titicut Follies (1967), about a Massachusetts institution for the criminally insane, I haven't seen in many years, but still flops meatily around in my head, rising up to stare back at me like old Nietzsche's abyss. This is a movie you cannot even see anymore; the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled it an invasion of the inmates' privacy, despite the fact it had already been filmed--and after the filmmakers were sued by the Commonwealth; maybe it was the Commonwealth's privacy that was invaded. (Where oh where did I see this, then? I'll bet it was on good old PBS, during the glory days of the 1970s, when it seemed devoted to film, from everywhere, about everything.) How's that for a living metaphor about the conflict between those who photograph, that which is photographed, and those who see?

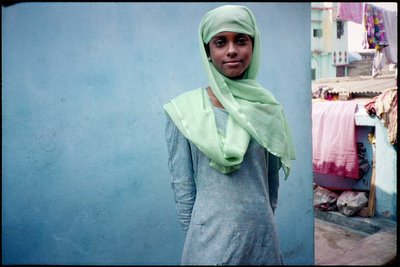

This was roiling around in the background as I watched Born into Brothels (2004), Zanna Briski and Ross Kauffman's documentary about "Calcutta's red light kids." Briski and Kauffman visited this nightmare district over a period of years, eventually training the children to take photographs, some of which were exhibited internationally. The film is sensitive and open-hearted, but the dilemma remains, compounded by the children's becoming photographers themselves: What is being served here? Art or humanity? Can one do both? Or are we stuck with a literal act of slumming, with these children, like Arbus', captured and sold?

Briski and Kauffman rise to the occasion, and become something like art's missionaries here, using the cameras like icon-making icons, or something--or better yet, like missals and hymnals, exhorting the children to rise and be saved. And it almost works: the filmmakers attempt to place the children in boarding schools where they can escape the inevitable descent into prostitution, abuse, and drug addiction. These children are not mere objects, but subjects, and the camera doesn't take, but gives. The sad truth that most of the children do not prosper--remaining in the red light district, or drifting from the schools--does not lessen the reciprocal nature of this artwork. Briski and Kauffman show us that the act of documentary appropriation, of the soul-stealing of the photograph, can be an exchange, not merely a surrender. Watching Born into Brothels, I lost that dizzy ache--which I will admit is probably the point of photographs of the underworlds; but this movie shows us you can ache and act, not merely watch and take.

Briski and Kauffman rise to the occasion, and become something like art's missionaries here, using the cameras like icon-making icons, or something--or better yet, like missals and hymnals, exhorting the children to rise and be saved. And it almost works: the filmmakers attempt to place the children in boarding schools where they can escape the inevitable descent into prostitution, abuse, and drug addiction. These children are not mere objects, but subjects, and the camera doesn't take, but gives. The sad truth that most of the children do not prosper--remaining in the red light district, or drifting from the schools--does not lessen the reciprocal nature of this artwork. Briski and Kauffman show us that the act of documentary appropriation, of the soul-stealing of the photograph, can be an exchange, not merely a surrender. Watching Born into Brothels, I lost that dizzy ache--which I will admit is probably the point of photographs of the underworlds; but this movie shows us you can ache and act, not merely watch and take.