I did not write last week, breaking so soon my promise to be diligent and post posthaste--and like a precious undergraduate I turned to a poem to urge me along: Wordsworth's "Resolution and Independence." I hadn't seen it in years, and had almost completely forgotten its beautiful opening stanzas on Nature in the morning; I was happy to read just for that image of the sprayline of dew raised by the running hare. And then of course that weird, almost off-putting heart of the poem, the encounter with the old leech-gatherer (and what a strange thing the job market was two hundred years ago). Wordsworth describes him as an apparition, compares him to a sea-creature that has emerged from the depths to sun itself. Reading the poem brought back the same combination of admiration and embarrassment one can feel with Wordsworth, he is so profound and silly all at once. Which in my mind makes him good--all right, monumental, in a fond and foolish way, a writer after my own ambitions, who can strike one as frighteningly insightful one moment, staring at you from the misty mists of time with clear understanding; and a little pathetic the next, straining for effect, reporting on the simple, albeit direct, surfaces of human faces without understanding them at all. But able to use them to build the damn poem.

I bring up Wordsworth to mark my own resolution--to write every day--and my own independence--from sloth, and hesitancy--and okay, so that I can "laugh myself to scorn," as Wordsworth famously closes, at the last moment saving the poem from impending mawkishness and providing me with a way back to the page. Dig We Must, yes, Faithful Reader? Even if you're not there, even if you're just me. So every day it will be. Starting today.

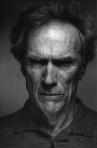

Clint Eastwood's Million Dollar Mea Culpa

WARNING: The following contains an elliptical but potentially damaging Million Dollar Baby spoiler.

I saw Million Dollar Baby over the weekend, and I am even more deeply convinced that when Eastwood is on he is formidable. But let me begin by damning with faint praise: Clint Eastwood is an earnest filmmaker. I'm still letting Wordsworth run around in my head as I consider Eastwood's flashes of brilliance combined with simple surfaces, all of it lovingly photographed and acted, eminently sustainable while the film runs, but sometimes too direct, almost bland in its forthright posture. The process of training Maggie Fitzgerald (Hilary Swank) is a case in point: the old grouch, Eastwood's Frankie Dunn, reluctantly allows Maggie to his inner circle, but not until she impresses everyone else, the audience most of all, with her pluck and yearning. In all seriousness, and I mean this as a compliment, I am reminded of Richard Gere's Zack Mayo in An Officer and a Gentleman (1982). Am I the only one still moved--against my will--by his admission, "I got nowhere else to go!"? Maybe I am; I checked, and the moment is not recorded on the Internet Movie Database's page of "memorable quotes" for the movie. Maggie, like Zack, comes from a white trash hell--Zack's relationship with his father, played by Robert Loggia with his usual ferocity (and I really must do something on Loggia some day), mirrors Maggie's encounters with a family whose troubles come "by the pound"--and we know, as does Morgan Freeman's Eddie "Scrap-Iron" Dupris, that Maggie must find her father, just as Zack found his father in Louis Gossett Jr.'s Sgt. Foley--and Dunn must in turn find his daughter, lost to him by an unnamed sin.

This is good stuff, but formulaic, and watching it I could feel Eastwood demand I feel for Maggie in certain ways, especially because her only early ally is Dupris, in a patented performance by Morgan Freeman, whose range may not be broad, but always pitch-perfect, and as reassuring as a loving God. Eastwood knew this in Unforgiven (1992), and boy-howdy he still does. Freeman allows us to accept Maggie as more than another oddball wannabe, some non-developmentally disabled version of Jay Baruchel's "Danger" Barch. We believe in her, and know Dunn's conversion is only a matter of time.

But of course Million Dollar Baby is not just another boxing picture with a father-finds-surrogate-daughter slant--although in many ways it is simply that. But, again, Eastwood is serious about something here, and as his and Swank's performances sink deeper into the material, as they draw us into their fears and hopes, the formula is transcended, broken, and reconfigured. Of course, I'm referring to Dunn's religious convictions, as tortured as Gerard Manley Hopkins', who at one point in his "terrible sonnets" exclaims, "I lay wrestling with (my God!) my God." And gosh, as long as it's Poets' Day, I wonder whether Frankie Dunn is John Donne, needing to find himself asserting that "no man is an island"? I'll let that go, but Frankie's faith, as sardonic as it is, still runs deep; and this provides the second tier: Dunn's decision in light of Maggie's suffering to play a role in her death. I would argue that Frankie's priest is correct: He warns Dunn that doing what he plans will destroy him; he will be lost to himself, if not to God. This becomes his sacrifice for Maggie.

So Dunn loses himself for Maggie's sake. That sounds dangerously like it might lead to a Deep Thought, and I think it does, raising the movie to a moral height I haven't seen in a while. And Eastwood forces us to stay eyes wide open despite the height. Keep in mind that the evil German boxer disappears; Eastwood refuses to give us the facile satisfaction of "seeing Justice done." Instead, he manages to make a statement that stands at the center of my own faith: We may seek justice, but what we really need is mercy. Furthermore, as Dunn's priest says, even if you leave out Heaven and Hell, even if you leave out God, some things remain true, such as the fact that the steady heart of sacrifice beats without thought of reward. So in the end the movie is simple and terrible, beautiful in its insistence that Dunn may have done something wrong, but it was still a moral decision, mysterious, hidden from our partial understanding, led relentlessly by mercy and the need to atone.

No comments:

Post a Comment