My parents were of The Movie Generation, putting up with all kinds of low-budget junk, mid-budget snores, big-budget disappointments. Their response to film was paradoxical, at once valueless, forgiving, uncritical, and enthralled, engrossed, entrenched. My Dad told stories, which I thought of as continuous showings, of watching The Outlaw (1943) when he was sixteen or seventeen, and being convinced with his other South Philadelphia friends--guys with Our Gang nicknames like Measles and Doggy and Pajamas--that something needed to be done to honor Jane Russell, some monument erected (sorry, couldn't resist), a statue built. I could see my father molding it by hand--so to speak--a ten-foot testament to Howard Hughes' devotion to the intricate concept of lift. Or seeing Gunga Din (1938)--I can still hear him pronounce it "Gunga DEEN"--and, convinced of its greatness, going back every day for a week, as he told it, to sit for the first show and stay all day. Or going to see Frankenstein--no doubt during one of its many re-releases--with someone he claims had never been to the movies before. When The Monster first appeared, in that famous close-up as Karloff enters the room with his back turned, and faces us silently, huge on the screen, that poor deprived kid screamed and ran out of the theater. I like to think he never went back, not even to see Pink Elephants on Parade in Dumbo. And my mother, who arrived here at seventeen from Cuba, and who learned English by looking at the Sunday funnies and, of course, going to the movies, was also a Compleat Viewer, willing to watch anything just so she could go regularly.

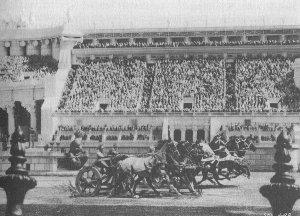

Together as adults, as my parents, they continued their habits, and lovingly drew my sister and me into the beautiful dark. Having moved to New Jersey when I was three, they would take lucky us across the Delaware back to Philadelphia to be overwhelmed by Cinerama colossi; to this day I refuse to admit that How the West Was Won (1962) is a bad picture; how can I, with that swooping curve looming still above me, that Big Sky and Waters soaring and rushing? Add to that the malls of South Jersey, with their audaciously big screens, crushing my willing form in the third row as Kubrick's monolith spun through space and Charlton Heston bounded defiantly across the Planet of the Apes. Television stood in at home, with Chiller Theater on Saturday nights and Shirley Temple and the Bowery Boys on Sunday mornings, and every sad B-picture in between.

So much of it was forgettable and weary, scratched and etched with the dust and stray hairs of long-gone projectionists. But it was all conditioning; I was in training, and my parents ran the camp. My father pointed out all those minor players and bedrock stalwarts: Frank McHugh with his sad-sack face and wheezy little laugh; Brian Donlevy and William Bendix, either blustering, glowering, or grinning; Gloria Grahame, that queen in exile, with Veronica Lake magically looking Alan Ladd square in the eye; and TV good guys causing havoc: Fred MacMurray in Double Indemnity and Raymond Burr in Rear Window. My mother knew the deeper waters of cinema, and insisted I see Midnight Cowboy. But she also loved a soap opera, and relished an opportunity to shed tears.

My parents taught me two great lessons. Once my father and I were watching a silent film; there was a crowd scene, and he remarked, "All those people are dead now." True, my father had a mordant sense of humor, but something else happened in me with that ghoulish observation: I saw the comfort of an unbroken chain of images extending across the decades. I began peering at the backgrounds of Three Stooges shorts for glimpses of 1940s Los Angeles; I noted the lost look in Peter Lorre's eyes that made me realize he wasn't just some pipsqueak menace; I stopped fretting about how fake city streets looked, and began looking forward to those outdoors filmed indoors. For her part, my mother showed me the power of narrative. She would get stuck with some awful drek, locked to the end, knowing it was bad, but willingly trapped. In one of his spookier songs--and that's saying a lot--Tom Waits whispers, "I want to know the same thing everybody does: How is it going to end?" Not to make too much of her obsessive viewing habits, but she was always someone who looked all the the way in and to the end of things; at the movies, she wanted to see it played out over and over, so that it could come out different--yet of course the same--every time.

Between a kind of Will Rogers attitude toward movies--I never (more or less) saw one I didn't like--and a tendency to scan the periphery of the frame, searching for something I didn't notice the first time, no matter how inconsequential, it seems I picked up some bad habits from my parents, for which I am thankful. Anyway, I've seen only one movie today, so--and let me apologize beforehand to W.B. Yeats--I must "arise and go now," for always I hear the reels spinning "in the deep heart's core."

No comments:

Post a Comment