At the end of chapter four of The Origin of Species, Darwin brings up the analogy of the tree of life. I can remember putting together construction-paper family trees in school--my children did the same, like every schoolkid. And my grandmother had a knick-knack, a small silver tree with tiny family photos hanging from the branches, her and my grandfather at the top, their three children lower down. That's backwards, but I didn't care. I was happy to see them all lined up, pendant from the tarnished silver, fuzzy images from the '50s. But I'm bringing up Darwin's tree because he writes about certain animals that enjoy "a protected station," and thrive like a low, straggling branch that should have withered, but lives on. Our pets are like that--and my apologies to George Orwell for taking his chilling punchline out of context, but they become for petowners more equal than other animals, a point insisted upon in Erol Morris' debut from 1980, a documentary about pet cemeteries, Gates of Heaven.

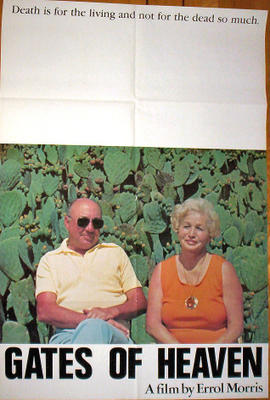

Morris made a landmark film, if only because in it he almost single-handedly invented the visual language of irony. Now there are precedents, including Andy Warhol's focus on the amateur and the accidental, the stumbling, lurching, leering kitsch manufactured in The Factory, where he charted the intersection of the ingenious and the disingenuous in a barely navigable course that Odysseus would've hesitated to follow. Morris, though, is not as scattershot or freewheeling. He holds still his subjects and leaves them be in an isolated space, where all they have is themselves. He frames them in self-consciously centered poses, almost as if they're being booked on suspicion (of being silly or crazy or simply stoned)--or they sit low in the frame, with the sky or a wall of cacti rising above their rock-still hunched forms, unconscious parodies of themselves. Morris' subjects are not interviewed; instead, they deliver monologues, often uncomfortably prompted to continue speaking by Morris' stubborn silence, a refusal to fill any dead air himself, while the camera relentlessly rolls. Like David Byrne's True Stories (1986), we become co-conspirators in a plot against the movie's subjects; we wonder whether we're being asked to laugh at them--or merely to laugh at them--or perhaps, in watching them unreel their sometimes-agonizing attempts to make sense, we become their protectors--or better yet, allies, insisting they be given their due, and even realizing the truth of their convictions, and the extent to which we share them.

This is the second time in as many years I've seen Gates of Heaven. The most recent was at Roger Ebert's Overlooked Film Festival in Champaign, Illinois. Morris was in attendance--and I will indulge and recount my Brush with Greatness. I was standing in the lobby of the Virginia Theatre, and felt something big to my right; it seemed to displace atoms, as though it had suddenly arrived via wormhole. I turned to it, and found myself looking at someone's sternum. I looked up, and it was Morris, six-feet-plus. I hesitated; do I act like a movie geek and bother this stranger, or play it cool and move on? I thought I was still deciding when I realized I was already shaking his hand and blathering--in my defense I will say it was relatively cool and collected blather, about how much I enjoyed his films, and some comment about the "Interrotron," his invention which acts as a kind of teleprompter, except that, through the magic of, I dunno, mirrors and prisms, while he is the one the subject is looking at, the result is a level gaze directly into the camera, rather than the slightly-off-to-the-side style of most documentary interviews; and then I asked him what he was doing, and he said he was looking for Roger; naturally, I crossed a line and offered to help find him. I immediately felt Morris assume a defensive posture, so to speak, a retreat managed without moving. I realized I had gone the way of all geeks, and let him be--stupid, because he walked ten feet away and into the theater, where Ebert and Werner Herzog were sitting in the back row. Another missed opportunity to stammer inanely.

But I digress.

Viewing Gates of Heaven at a film festival underlined its more postmodern qualities, especially the self-reflexive, referential, ironic elements. Still, watching the grainy print on the big screen gave Morris' pet lovers--and interrers--an inevitable magnitude. This served to make their foolishness more foolish, of course, but it also helped validate their commitment to making their animals more equal than others; and their love is expressed unselfconsciously, as they memorialize their pets and in the next breath discuss their fur coats and platters of meat ruined by the smells of exhumation and rendering. "A protected station," indeed.

The movie covers a lot of ground, but watching it yesterday I focused on the truths it told about pets and pet ownership: that becoming a pet removes one from the struggle for existence in a fundamental way; that owning a pet allows for a blissful, albeit partial, ignorance of one's shortcomings, while simultaneously providing an opportunity to generate an ideal in the form of the pet; that the need for contact is great, whether it be with the pet or, given its demise, Morris' Interrotron, which, when stared at and spoken into, validates the love felt for the pet. Near the end, Morris gives us a sequence of shots of dog and cat headstones. None of the memorials are dopey or campy or morbid; all of them are simple and unashamed in their affection for the pets. I found myself noticing the birth-death dates; many of the pets lived only two or three years, and yet they are accorded their due. Naturally, this never entirely stops being weird, but in that lingering sequence of shots, Morris seems to acknowledge the honesty of the petowners' love; the smarmy ironic wink is replaced by the respectful glance toward those small indicators of the need to "love and be loved," as Floyd McClure, the visionary but failed cemetery designer, described the two purposes of pets. I should be so lucky.

No comments:

Post a Comment