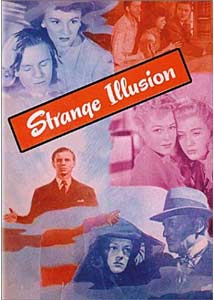

Appropriately enough, Edgar G. Ulmer's Strange Illusion (1945) begins with a dream: Paul Cartwright (Jimmy/James "Henry Aldrich" Lydon) walks with his mother and sister, while a shadowy father and Other go with them; and a train approaches, and sudden sentences are uttered, and anxiety builds. This is how I like to think of all of Ulmer's best movies, especially Detour (1945), The Strange Woman (1946--with a strange Hedy Lamarr performance), The Man from Planet X (1951), and his early masterpiece, The Black Cat (1934): dreams all, with a dream's low budget and big drop. Strange Illusion is perhaps the "lightest" of the films mentioned, although its smooth Hamlet references and queasy villain, Brett Curtis (part Bluebeard, part--believe it or not, in 1945--child molester, played with comforting '40s oiliness by Warren William, his pencil-thin mustache and low-rent Great Profile almost reassuring: after all, such an obvious cad--you know, more than kin and so on--looking like something Tex Avery might draw to chase around a hapless babe, is bound to be defeated--not to mention Paul's "sensitive" nature, played by Lydon with his usual gee-whiz faintness, all give Strange Illusion a decidedly tilted posture; like its dream-pursued, melancholy hero, it seems more than a little light-headed.

But chock-full of plot. The Hamlet-lifting serves it well: Paul's judge/criminologist father is killed in a train "accident," and Paul, markedly attached to him--and his mother (Sally Eilers, just hefty enough to look like a widow, but young enough to provide a Freudian whiff)--is haunted by a dream--which propels him to find his father's killer: Curtis, of course, pursuing Paul's mother, charming his sister--but creeping out his girlfriend, who suffers Curtis' deep-end affections in the pool--not shown, of course, but related to Paul as further evidence that Curtis is the movie's pre-nuptial Claudius, with an even bigger appetite than Shakespeare's killer. Curtis' confederate, a crooked psychiatrist, adds to the Ulmer-esque weirdness of the movie as he, Svengali-like, guides his former patient through the machinations necessary to get him married to the judge's widow--and thus ensconce him in the only family that could prove who and what he is (remember the dead father was a criminologist). Again, this is a plot that needs no thickening; from its dream beginning, it's one thing or another.

But chock-full of plot. The Hamlet-lifting serves it well: Paul's judge/criminologist father is killed in a train "accident," and Paul, markedly attached to him--and his mother (Sally Eilers, just hefty enough to look like a widow, but young enough to provide a Freudian whiff)--is haunted by a dream--which propels him to find his father's killer: Curtis, of course, pursuing Paul's mother, charming his sister--but creeping out his girlfriend, who suffers Curtis' deep-end affections in the pool--not shown, of course, but related to Paul as further evidence that Curtis is the movie's pre-nuptial Claudius, with an even bigger appetite than Shakespeare's killer. Curtis' confederate, a crooked psychiatrist, adds to the Ulmer-esque weirdness of the movie as he, Svengali-like, guides his former patient through the machinations necessary to get him married to the judge's widow--and thus ensconce him in the only family that could prove who and what he is (remember the dead father was a criminologist). Again, this is a plot that needs no thickening; from its dream beginning, it's one thing or another.My only regret is that Strange Illusion ends up loving its plot too much, giving us, as one "bmacy from Western New York" put it on the Internet Movie Database, a "Hardy Boys" movie. I guess I wished for something more delirious, like Detour's clueless descent or The Black Cat's full-blown dementia. But Strange Illusion does provide a clear sense of Ulmer's strengths: his ability to keep things moving, his affinity for abnormal psychology, and his affection for shadows. And, in a Saturday-afternoon kind of way, it is enough, another Ulmer effort set "in the dead vast and the middle of the night."

From Lydon's 1941 high school yearbook: "A redhead Irishman who likes nothing better than a good argument. His aim is to be a pilot and a motion picture cameraman. Jim becomes positively poetic about roast lamb and apple pie." This is someone I would've liked to have known.

From Lydon's 1941 high school yearbook: "A redhead Irishman who likes nothing better than a good argument. His aim is to be a pilot and a motion picture cameraman. Jim becomes positively poetic about roast lamb and apple pie." This is someone I would've liked to have known.

No comments:

Post a Comment