I work--ah, "work" is such a dry word to describe the cornfield glories of my career amid the missionaries and muckrackers; but it'll do--at Knox College, which requires its incoming students to take First-Year Preceptorial (FP), a common course that uses a variety of texts--including films--to "discuss broadly based, fundamental issues that define the human condition and inform significant choice." You know, the small stuff. Since 1993 I've been working with students writing papers for the course, and since last year I've had the chance to teach it. FP is one of those split-decision courses: those who teach it often love it, while those who take it often don't. And while some become exasperated with the course materials, or the students/faculty, or the course itself--oh, the bane of anything "required"--others keep the FP fire burning in their hearts throughout their teaching careers or educations--and beyond: I've had students who've graduated and told me that FP crops up at the oddest moments, especially the ethical dilemma ones, or human nature ones. You know, the big stuff.

Me, I'm one of those who love FP. Geez, that sounds like a bumper sticker, but I canna help it: Over the years, FP has excitedly asked students to play with all kinds of firecrackers, from "Heart of Darkness" and Things Fall Apart to The Moral Animal and the Book of Genesis (the falling-down parts). We've heard Rousseau rail against civilization even as Hobbes raised the beast to secular godhood. And Frankenstein tried to make it happen, Cap'n, while Joyce Carol Oates asked the students where they're going and where they've been--and Marx told them exactly where, and what to do about it--the weatherman is always right, yes?--while Darwin inherited something more than the wind. And we've watched Kane let everybody know who he is, while Alex and his droogs ate much more than lomticks of toast, their eggiwegs swinging with the force of tawdry doom.

Me, I'm one of those who love FP. Geez, that sounds like a bumper sticker, but I canna help it: Over the years, FP has excitedly asked students to play with all kinds of firecrackers, from "Heart of Darkness" and Things Fall Apart to The Moral Animal and the Book of Genesis (the falling-down parts). We've heard Rousseau rail against civilization even as Hobbes raised the beast to secular godhood. And Frankenstein tried to make it happen, Cap'n, while Joyce Carol Oates asked the students where they're going and where they've been--and Marx told them exactly where, and what to do about it--the weatherman is always right, yes?--while Darwin inherited something more than the wind. And we've watched Kane let everybody know who he is, while Alex and his droogs ate much more than lomticks of toast, their eggiwegs swinging with the force of tawdry doom.And speaking of watching, this year a pro-movie swell is rolling by the Good Ship FP, so over the past few weeks some of us have been watching films that might fellow-travel with our main readings (Kwame Appiah's Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, and Mary Doria Russell's novel of Jesuits in space, The Sparrow; we also have The New Humanities Reader, for picking and choosing, well, readings in the humanities that are, more or less, new). So far we've watched Costa-Gavras' Amen, Hotel Rwanda, Rabbit-Proof Fence, and Spike Lee's Malcolm X biopic. (Next week is The Battle of Algiers and some docs.) Of course, I'm a hunnert percent behind the effort to include films in the course, but a funny thing keeps happening after we watch a movie: We think of ways the film under discussion would not work. Now, some of these objections make perfect sense: Does the film add to our discussion? Are its ideas self-evident, or is it not "cinematic" enough for us to focus on technique, structure, editing, music, and so on? It's a sad but true winnowing, in which there seems more chaff than wheat.

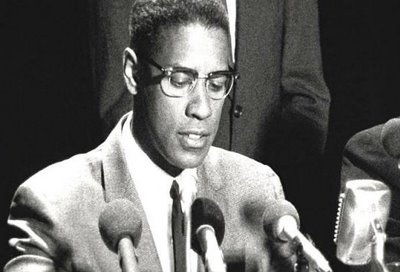

But we continue to fan the breeze, viewing Malcolm X (1992) last night. I hadn't seen it in five years or so, and was determined to watch closely, to draw to the surface Lee's best touches, his most enduring contributions to the story. And I did see--and hear--much I had not remembered. From the opening title sequence, in which a flag covers the screen, while Lee cuts to scenes of the Rodney King beating--fresh wounds in 1992--and the flag eventually burns, slapping us with the left hand of Patton--to Malcolm in his final moments, his head literally spinning as the camera rotates 360 degrees. And I saw many Scorsese-like touches, in which Malcolm positions himself as Jake LaMotta stripped down to raw muscle, or Christ leaning toward, then away from, last temptations. And the soundtrack always supplies the perfect song, whether as complement or counterpoint--with Terence Blanchard's score, bold in its percussive, symphonic flourishes, willing to take chances: In the Mecca scenes, for instance, he generates a kind of post-Les Baxter exotica mood that never slips into kitsch. And there are individual moments, especially early on and in its final scenes, in which Vincente Minelli and Oliver Stone seem to vie for Lee's attention and, to the movie's benefit, get it.

But we continue to fan the breeze, viewing Malcolm X (1992) last night. I hadn't seen it in five years or so, and was determined to watch closely, to draw to the surface Lee's best touches, his most enduring contributions to the story. And I did see--and hear--much I had not remembered. From the opening title sequence, in which a flag covers the screen, while Lee cuts to scenes of the Rodney King beating--fresh wounds in 1992--and the flag eventually burns, slapping us with the left hand of Patton--to Malcolm in his final moments, his head literally spinning as the camera rotates 360 degrees. And I saw many Scorsese-like touches, in which Malcolm positions himself as Jake LaMotta stripped down to raw muscle, or Christ leaning toward, then away from, last temptations. And the soundtrack always supplies the perfect song, whether as complement or counterpoint--with Terence Blanchard's score, bold in its percussive, symphonic flourishes, willing to take chances: In the Mecca scenes, for instance, he generates a kind of post-Les Baxter exotica mood that never slips into kitsch. And there are individual moments, especially early on and in its final scenes, in which Vincente Minelli and Oliver Stone seem to vie for Lee's attention and, to the movie's benefit, get it. We were still not sure, though, whether we wanted the students to watch the movie. We discussed showing individual scenes, or breaking it up in two, or making it an ancillary film, off to the side somewhere. But the more I think about it--and write about it now--the more I trust Lee's movie. We could not fail to notice Denzel Washington's achievement, as he captures Malcolm's charisma--or Angela Bassett as his wife Betty, who naturally is the first to see that misogyny ends in lies and shame. I think we should show Malcolm X--or at least I will, and take the time to offer FP students a chance to recognize the visual/aural contributions of a "film experience." And we won't even need to do so by any means necessary; just a handful of good movies.

We were still not sure, though, whether we wanted the students to watch the movie. We discussed showing individual scenes, or breaking it up in two, or making it an ancillary film, off to the side somewhere. But the more I think about it--and write about it now--the more I trust Lee's movie. We could not fail to notice Denzel Washington's achievement, as he captures Malcolm's charisma--or Angela Bassett as his wife Betty, who naturally is the first to see that misogyny ends in lies and shame. I think we should show Malcolm X--or at least I will, and take the time to offer FP students a chance to recognize the visual/aural contributions of a "film experience." And we won't even need to do so by any means necessary; just a handful of good movies.

No comments:

Post a Comment