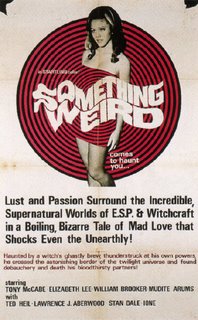

Ever see something weird? How about Something Weird, the movie (1967)? Or Something Weird, the video distribution company? If you've seen the first, it was probably courtesy of the last, which named itself after the second. Weird.

Ever see something weird? How about Something Weird, the movie (1967)? Or Something Weird, the video distribution company? If you've seen the first, it was probably courtesy of the last, which named itself after the second. Weird.Along with the sainted supergeeks of Rhino, SWV keeps alive the odd corners of cinematic delirium, where they save Hitler's brain and ask to be colored blood red, where jungle women and killer tomatoes--and shrews--attack, where one can enjoy not only a smell of honey but a swallow of brine; in short, a trashbin with aspirations to be an archive.

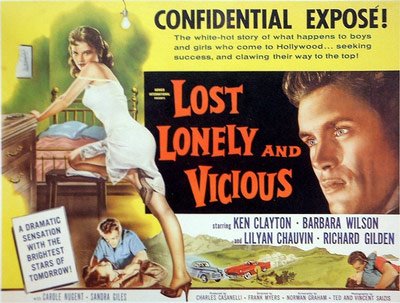

And every once in a while I admit I dive into this 16-millimeter dumpster, fulfilling long after midnight the hesitant, half-admitted, guiltiest pleasures of my life in movies. And unfortunately--and inevitably--the actual experience of watching one of them is not often as, ahem, satisfying as I'd hoped. This makes sense; after all, there is something quintessentially adolescent about the impulse to watch movies with titles like Orgy of the Dead (1965), Anatomy of a Psycho (1961), or The Rebel Set (1959)--"Today's Big Jolt about the Beatnik Jungle!"--let alone Primitive Love (1964), The Bizarre Ones (1967)--which promised exactly what I wanted, "A Change from the Normal Life"--or what may be my favorite title in all of exploitation cinema (not the least because two dear friends once gave me a postcard-book of movie posters with this title), Lost, Lonely and Vicious (1957). These movies capture the humid little soul of exploitation: All the entertainment you're going to get occurs before the movie actually starts--aside from the quasi-condescending fun of making fun of the damaged, defenseless thing itself.

And every once in a while I admit I dive into this 16-millimeter dumpster, fulfilling long after midnight the hesitant, half-admitted, guiltiest pleasures of my life in movies. And unfortunately--and inevitably--the actual experience of watching one of them is not often as, ahem, satisfying as I'd hoped. This makes sense; after all, there is something quintessentially adolescent about the impulse to watch movies with titles like Orgy of the Dead (1965), Anatomy of a Psycho (1961), or The Rebel Set (1959)--"Today's Big Jolt about the Beatnik Jungle!"--let alone Primitive Love (1964), The Bizarre Ones (1967)--which promised exactly what I wanted, "A Change from the Normal Life"--or what may be my favorite title in all of exploitation cinema (not the least because two dear friends once gave me a postcard-book of movie posters with this title), Lost, Lonely and Vicious (1957). These movies capture the humid little soul of exploitation: All the entertainment you're going to get occurs before the movie actually starts--aside from the quasi-condescending fun of making fun of the damaged, defenseless thing itself.  But it is precisely the adolescent nature of the urge to watch such movies that drives me back to them, despite evidence to the contrary that this time things will be different, this time I'm going to be plunged into a grainy dreamworld of unselfconscious id-exposure, where "camp" and "kitsch" wilt in the high-contrast glare of the sudden lurching fulfillment of cinema's persistent promise of a glimpse of the First Image, in which society and self disappear, and all that's left in the secret garden are the tender shoots, almost emergent, but vague in their final, pure shape.

But it is precisely the adolescent nature of the urge to watch such movies that drives me back to them, despite evidence to the contrary that this time things will be different, this time I'm going to be plunged into a grainy dreamworld of unselfconscious id-exposure, where "camp" and "kitsch" wilt in the high-contrast glare of the sudden lurching fulfillment of cinema's persistent promise of a glimpse of the First Image, in which society and self disappear, and all that's left in the secret garden are the tender shoots, almost emergent, but vague in their final, pure shape. And some of these movies get close, at least in moments. But I so often get only stuff and nonsense that I am forced to remind myself that the people who actually made these movies were simply sticking their stubby little fingers into movie-marketing's shallower niches, and their dogged desire to cash in makes their films as empty of potential as their big-budget counterparts, both so cynical in their intents that their movies have no room for any persistent images.

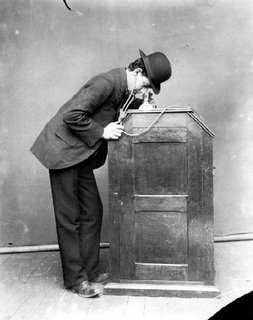

Unless I make them persist. I watched The Monster That Killed Women (1965), working in a sub-genre--nudist camp--that is particularly unlikely to provide evidence of cinema's substrata, if only because of its self-imposed restriction to provide redundant nudity within set parameters, most of which involve activities that allow women to sit on the ground together, huddle in bunk beds together, or play endless games of volleyball--not to mention the, shall we say undulatory effects, of the physical actions attendant upon reaching for objects--beach towels, board games--inexplicably placed on high walls and shelves. And even more inhibiting are the demands of what we can call with Continental delicacy La promenade en deshabille, in which figures pass the unmoving camera so that the viewer can receive a flat, semi-unobstructed perspective as they saunter by.

Unless I make them persist. I watched The Monster That Killed Women (1965), working in a sub-genre--nudist camp--that is particularly unlikely to provide evidence of cinema's substrata, if only because of its self-imposed restriction to provide redundant nudity within set parameters, most of which involve activities that allow women to sit on the ground together, huddle in bunk beds together, or play endless games of volleyball--not to mention the, shall we say undulatory effects, of the physical actions attendant upon reaching for objects--beach towels, board games--inexplicably placed on high walls and shelves. And even more inhibiting are the demands of what we can call with Continental delicacy La promenade en deshabille, in which figures pass the unmoving camera so that the viewer can receive a flat, semi-unobstructed perspective as they saunter by. But it was here, in the promenade, that I heard a whispered hint of exploitation cinema's hold on me, more than in all the campfire sing-alongs, changing-room confabs, and shuffleboard matches combined. The women* walk away from the camera and make their way over a small hill or behind some foliage, or toward the camera--but in this case filmed from the waist up, or at such an angle that we cannot visit the Netherlands, if I may be discreet. These shots are so nonchalant, and so often repeated, that the fact of voyeurism is absolutely exposed, so to speak. No metaphors remain to provide ironic--let alone erotic--distance, no membrane separates the watcher from the intent to watch. And watching this movie myself, I wondered at what point in my life I would not have been bored by these scenes. And that of course would be in adolescence. At fourteen, I would have found the promenade to be the center of these films--the kinetic dynamics of volleyball notwithstanding--and I can easily see myself disappointed when the movie reluctantly returned to its "plot."

Because, watching it now, the promenade of course is the plot, if "plot" equals "point." And, as I watched the individual promenades--three or four of them--of The Beast That Killed Women (and for now I will not discuss the self-evident, nasty connection in these movies between violence and nudity), I found myself passing beyond boredom and into a dimly lit quiet place, where my adolescent libidinal instincts looked up at me from the bottom of Time's hill to remind me that, as in the myth of Sisyphus (something I seem to get back to all the time), climbing that hill precipitates returning to the hollow, the shadowed low place where I can rest for a moment, but which I also know I need to climb back up. It is a promenade itself, beautiful and foolish, for me a necessary circuit--because I swear the hill gets higher every time I climb it; all I can hope is that I get stronger with every climb. After all, they say walking is the best exercise.

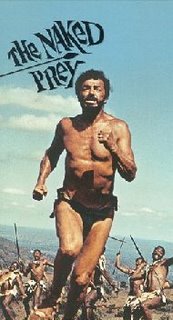

Because, watching it now, the promenade of course is the plot, if "plot" equals "point." And, as I watched the individual promenades--three or four of them--of The Beast That Killed Women (and for now I will not discuss the self-evident, nasty connection in these movies between violence and nudity), I found myself passing beyond boredom and into a dimly lit quiet place, where my adolescent libidinal instincts looked up at me from the bottom of Time's hill to remind me that, as in the myth of Sisyphus (something I seem to get back to all the time), climbing that hill precipitates returning to the hollow, the shadowed low place where I can rest for a moment, but which I also know I need to climb back up. It is a promenade itself, beautiful and foolish, for me a necessary circuit--because I swear the hill gets higher every time I climb it; all I can hope is that I get stronger with every climb. After all, they say walking is the best exercise. *And men--but they don't count; the men in these movies are often wearing swim trunks (which I would guess was a relief to the nervous, at the least slightly damaged males who were the target audience for these movies), and, given the frontal nudity restrictions that apply to both sexes--nothing below the belt--even nude they offer nothing more (boy, is this getting creepy) than Charlton Heston already had in Planet of the Apes (1968)--or, come to think of it, Cornel Wilde in The Naked Prey (1966) (by the way another movie that resides in my memory as a primordial film experience; I fear, though, that if I ever see it again it, too, will become a triviality).

*And men--but they don't count; the men in these movies are often wearing swim trunks (which I would guess was a relief to the nervous, at the least slightly damaged males who were the target audience for these movies), and, given the frontal nudity restrictions that apply to both sexes--nothing below the belt--even nude they offer nothing more (boy, is this getting creepy) than Charlton Heston already had in Planet of the Apes (1968)--or, come to think of it, Cornel Wilde in The Naked Prey (1966) (by the way another movie that resides in my memory as a primordial film experience; I fear, though, that if I ever see it again it, too, will become a triviality).

No comments:

Post a Comment