I know someone, a young man in his early twenties, who thinks about George Romero's zombies all the time. Whenever he enters a room, a little careful part of his brain has him scope out all entrances and exits. He doesn't like to be alone, and facing a door or ground-level window only makes it marginally better. Outdoors isn't so bad, but there needs to be a lot of open space; even then, he keeps in mind that Romero's first victims were in a big cemetery, and could see Doom coming a long way off. When he confessed this fear to me, no doubt during one of my ecstatic outpourings on movies, I probably wasn't even talking about Romero; but something in my wide-eyed rush of words provided him an opening to tell me of his fear. One madman to another.

At first, I almost congratulated him. After all, here we are in a time when we've slopped around in every evil, twice, and come up grinning, like those pretty young people I saw triumphantly clenching dead rats in their teeth on TV's Fear Factor; a time too Gonzo for Dr. Thompson--who stared down the slavering jaws of the Were-Nixon--too twisted for Bruno Bettelheim --who survived Buchenwald and Dachau and knew what the wolf dreamed of while waiting for Little Red Riding Hood to show up--and definitely too much for Karel Capek, the Czechoslovakian writer who gave us the word "robot," and who was perhaps the first casualty of the modern age, wasting away, his heart broken, when it was clear no one was going to stop Hitler in time. You'd assume that after all those affronts, nothing could faze anybody under thirty anymore. I thought it was good to see a little atavistic fear still tinkling the ivories of the spine. Of course, though, the more that young zombie-phobe talked, the worse I felt for him. This fear dogged him, silent in the underbrush of his life, always out of sight but never out of mind.

I have nothing new to say here, except to acknowledge how thoroughly George Romero understands the nature of the terror of evil, at least when he's making zombie movies. Some day I will write about something a friend once said off the cuff and long ago and far away in 1980, that The Shining was about the banality of evil. Note to self: I owe Hannah Arendt a posting.* For now, though, Romero: He knows dread, and how it is linked to the rooms we sit in and the scenery we move through, and how dread comes at us, its shambling, E.C. horror comics/Karloff as The Mummy gait laughably slow--but so darn inexorable, like plate tectonics, so that you cannot escape the object of dread: consumption. In Romero's Dead movies, evil may be silly or slimy, but it is always as close as the dinner table or the shopping center, the personal and social feeding grounds. So when that young man admitted he was always thinking of zombies, he was just seeing Romero's version of the Post-Everything Age. In Flannery O'Connor's Wise Blood--by the way, made into a 1979 movie that needs to be on DVD--Hazel Motes founds the "Church of Christ Without Christ," where "the blind don't see, the lame can't walk, and the dead stay that way." I wish someone would tell that to Romero; in the meantime, we'll keep our eye on the door.

*Still do.

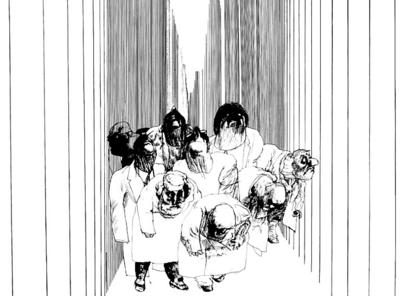

The illustration is by Ralph Steadman; it's called "America," and makes me realize that if anyone at this late date wants to produce a Romero Dead graphic novel, he's the one. And re-reading--and fussing with--the post helps me sort out my latest viewing of Night of the Living Dead (1968), an event instigated by my son, who wants to see them in order. He may be a bit young--thirteen in a few weeks--but he saw a profile of Romero on G4, the video game network, so it's all right. (All together now, quoting Jack Torrance in The Shining responding to Danny's casual attitude to the story of the Donner Party: "He saw it on the television." Hoo-boy; once again, life imitates.) G4, eh? And here I thought it was my constant tutelage that had him interested in the ooky Romero oeuvre, my studied fascination with the history and theory of horror, augmented by an encyclopedic knowledge of the genre which--oh, right: G4 it is.

And what did I see? something new? Not really, but the more I think about it, the more I realize I saw something worse: the film's absolute refusal to play by the rules, let alone offer any hope of a way out. I remember reading somewhere a critic who observed how the movie upends our expectations, giving us a Black hero, forcing the hysterical female to remain in shock far longer than she would in a conventional horror film--but this goes on and on, deeper and deeper, because the hero is wrong about everything: The weasely guy who wanted to stay in the cellar was right. He knew that every effort to escape was doomed, that staying in the house was a death sentence, that the cellar would withstand an attack by the massed zombies--no, "ghouls," as the pitch-perfect reporters refer to them in what may the film's greatest effect: on-air verisimilitude, with local anchors sounding like, well, local anchors, and hurried street-side press conferences loaded with stammering near-contradictions. Those radio and TV broadcasts make the holocaust ring truer than all the pig intestines tossed and torn. Again, though, it is all thwarted: every hope of heroic strength and savvy, every decision to survive. Poor Barbara: When she finally breaks free of her shock-stupor, it is only to fling herself into the grasping hands of the ghouls, with her brother, naturally, at the fore, his "They're coming to get you" joke altered in its pronoun to "I." Romero, I had written, knows dread. But of what? Of best-laid plans, good intentions--and good deeds, which become the central bitter old joke of the movie: None of them go unpunished.

And what did I see? something new? Not really, but the more I think about it, the more I realize I saw something worse: the film's absolute refusal to play by the rules, let alone offer any hope of a way out. I remember reading somewhere a critic who observed how the movie upends our expectations, giving us a Black hero, forcing the hysterical female to remain in shock far longer than she would in a conventional horror film--but this goes on and on, deeper and deeper, because the hero is wrong about everything: The weasely guy who wanted to stay in the cellar was right. He knew that every effort to escape was doomed, that staying in the house was a death sentence, that the cellar would withstand an attack by the massed zombies--no, "ghouls," as the pitch-perfect reporters refer to them in what may the film's greatest effect: on-air verisimilitude, with local anchors sounding like, well, local anchors, and hurried street-side press conferences loaded with stammering near-contradictions. Those radio and TV broadcasts make the holocaust ring truer than all the pig intestines tossed and torn. Again, though, it is all thwarted: every hope of heroic strength and savvy, every decision to survive. Poor Barbara: When she finally breaks free of her shock-stupor, it is only to fling herself into the grasping hands of the ghouls, with her brother, naturally, at the fore, his "They're coming to get you" joke altered in its pronoun to "I." Romero, I had written, knows dread. But of what? Of best-laid plans, good intentions--and good deeds, which become the central bitter old joke of the movie: None of them go unpunished.  I thought it would be fun to watch Romero's Dead movies in a row. But I've had a bad beginning. I'm afraid the satire of Dawn and the indictments of Day will be dimmed by blood--and not Tom Savini's Niagara of red red krovvy, but the tide that is loosed by the first film, drowning the ceremony of innocence, and leaving us on the wasted road to perdition. Well, that's that. All I'm left with right now in my head is Homer Simpson gravely advising, "If at first you don't succeed, give up." Thanks, George. I'll keep watching, but I know I shall hateth myself cometh the Dawn.

I thought it would be fun to watch Romero's Dead movies in a row. But I've had a bad beginning. I'm afraid the satire of Dawn and the indictments of Day will be dimmed by blood--and not Tom Savini's Niagara of red red krovvy, but the tide that is loosed by the first film, drowning the ceremony of innocence, and leaving us on the wasted road to perdition. Well, that's that. All I'm left with right now in my head is Homer Simpson gravely advising, "If at first you don't succeed, give up." Thanks, George. I'll keep watching, but I know I shall hateth myself cometh the Dawn.

1 comment:

Keep it blazin!

Holla!

Post a Comment