I was lucky to have Fr. Jack as a religion teacher in high school. This was in the early '70s, at an all-boys Catholic high school--OK, they called it a "preparatory" school--and OK again, I think they did prep us for college pretty well; but what I mostly remember was the charged atmosphere of the place, especially once you factored in a pretty strong contingent of rich Italian kids, little Sopranos whose fathers were building contractors and funeral home owners (yes of course), all of them sharp dressers who could curse like sailors--as we all did, but never in front of adults--and each mamma mia's son of 'em loaded for bear; the fights were fierce but quick. I cannot watch a movie fistfight without disapproval because in high school, when someone was hit real hard, they fell right down, fast, without ceremony, like dropping--no, throwing--a rock. And the teachers were physical creatures as well, tossing us around pretty easily, casual and businesslike as they threw us against our lockers or rapped us on the heads with ballpoint pens or yanked us from our seats by the hair on our temples to kneel at the blackboard in front of the classroom--where the crucifix was--to pray for forgiveness for talking during study hall. I was relieved when these things happened to me; such treatment raised one, no matter how temporarily, from the substratum where victims languished. I was not smart enough to be among the ultra-honor students, who were generally ignored, so being manhandled by teachers mimimized peer-handling. Watching Goodfellas the first time was a bit unsettling. Sixteen years after high school, and I still cringed as Henry Hill reminded me, "If we wanted something we just took it. If anyone complained twice they got hit so bad, believe me, they never complained again." Funny guys.

But this is not what I wanted to write about. I started with Fr. Jack--his last name escapes me--and I can say unselfconsciously he was a cool teacher, a laid-back post-Vatican II type who looked like Dean Martin--and acted like him, with his casual, head-tilting grin, his pompadour'd hair glistening, his eyes serene. I remember him proctoring an exam and letting kids go to the bathroom whom we all, Fr. Jack included, knew were going to look up answers. He'd just shake his head, half-smiling, and wave his hand after them. Their loss, I think he figured. He once held up his priestly keychain--not like Peter's, but crammed with the way in to every place on campus--and talked about how he wouldn't need them if we really were good Christians. And I'm happy to report he didn't say "man" at the end of such proclamations; he didn't need to, he was so cool.

But this is not what I wanted to write about. I started with Fr. Jack--his last name escapes me--and I can say unselfconsciously he was a cool teacher, a laid-back post-Vatican II type who looked like Dean Martin--and acted like him, with his casual, head-tilting grin, his pompadour'd hair glistening, his eyes serene. I remember him proctoring an exam and letting kids go to the bathroom whom we all, Fr. Jack included, knew were going to look up answers. He'd just shake his head, half-smiling, and wave his hand after them. Their loss, I think he figured. He once held up his priestly keychain--not like Peter's, but crammed with the way in to every place on campus--and talked about how he wouldn't need them if we really were good Christians. And I'm happy to report he didn't say "man" at the end of such proclamations; he didn't need to, he was so cool.  Actually, the coolest: In religion class he showed us Pier Paolo Pasolini's The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964). This was, if I may use such language, a transfiguring experience. Remember, the original recording of Jesus Christ Superstar was released in 1970, so the "rocks and stones themselves" were singing all over the place--in fact, I can remember my class going to a weekend Retreat where at one point we simply sat around and listened to that boss album. But Fr. Jack de-commodified the Jesus Happening with Pasolini's docu-drama of a straight-faced Jesus Who was as much man as God--a true theologic achievement, the mathematically impossible doubling--100% one, 100% the Other--that the nuns told the truth about when they said it was a Mystery of the Church. And Pasolini seemed to accept this Mystery, whether it be Joyful or Sorrowful, so that he could forge ahead.

Actually, the coolest: In religion class he showed us Pier Paolo Pasolini's The Gospel According to St. Matthew (1964). This was, if I may use such language, a transfiguring experience. Remember, the original recording of Jesus Christ Superstar was released in 1970, so the "rocks and stones themselves" were singing all over the place--in fact, I can remember my class going to a weekend Retreat where at one point we simply sat around and listened to that boss album. But Fr. Jack de-commodified the Jesus Happening with Pasolini's docu-drama of a straight-faced Jesus Who was as much man as God--a true theologic achievement, the mathematically impossible doubling--100% one, 100% the Other--that the nuns told the truth about when they said it was a Mystery of the Church. And Pasolini seemed to accept this Mystery, whether it be Joyful or Sorrowful, so that he could forge ahead.  What I remembered for decades later--having only seen it that one time until just now--was the matter-of-fact way Pasolini's Jesus* expressed Matthew's words, even the hard ones--but I was especially struck by his scorn for the rich, his insistence on keeping children at his feet while he held up the eye of the needle, a taunting dismissal. In 1971 or so, when Fr. Jack screened the movie, this is exactly the Jesus I needed. At the time, I was ready to accept a secular, self-invented savior--you know, the great philosopher, the wise man, on whom I could depend for recognizable advice--because there I was, also reading Siddhartha, already yearning for any kind of righteous, selfless life. And I hoped I could manage it without the burden of Mystery.

What I remembered for decades later--having only seen it that one time until just now--was the matter-of-fact way Pasolini's Jesus* expressed Matthew's words, even the hard ones--but I was especially struck by his scorn for the rich, his insistence on keeping children at his feet while he held up the eye of the needle, a taunting dismissal. In 1971 or so, when Fr. Jack screened the movie, this is exactly the Jesus I needed. At the time, I was ready to accept a secular, self-invented savior--you know, the great philosopher, the wise man, on whom I could depend for recognizable advice--because there I was, also reading Siddhartha, already yearning for any kind of righteous, selfless life. And I hoped I could manage it without the burden of Mystery.  Pasolini's film nudges along that hope--except he leaves in the miracles. And seeing the film again I saw how realistic they were as physical actions, as real as any of the words of Matthew's/Pasolini's poet-reformer. Roger Ebert points out that the "miracles are treated in a low key." For instance, when Jesus walks on the water, there is "[n]o triumphant music, no waving of hands and shouts of incredulity, no sensational camera angles -- just a long shot of a solitary figure walking on the water." Watching the film in high school, I was able to take advantage of this approach and focus on the social message, and in doing so hold on to some version of my faith for just enough years to keep it, wrestling partner and friend, always right there before me, as much lit by Fr. Jack's bright eyes as scolded by his rueful grin at my own trips to the liar's lavatory, where all employees must wash hands before leaving.

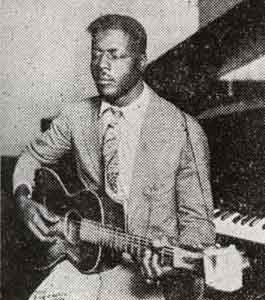

Pasolini's film nudges along that hope--except he leaves in the miracles. And seeing the film again I saw how realistic they were as physical actions, as real as any of the words of Matthew's/Pasolini's poet-reformer. Roger Ebert points out that the "miracles are treated in a low key." For instance, when Jesus walks on the water, there is "[n]o triumphant music, no waving of hands and shouts of incredulity, no sensational camera angles -- just a long shot of a solitary figure walking on the water." Watching the film in high school, I was able to take advantage of this approach and focus on the social message, and in doing so hold on to some version of my faith for just enough years to keep it, wrestling partner and friend, always right there before me, as much lit by Fr. Jack's bright eyes as scolded by his rueful grin at my own trips to the liar's lavatory, where all employees must wash hands before leaving. And watching it now, one more thing is added, something that took me completely by surprise, and froze me in my tracks once again: In high school I had not noticed that Pasolini used all kinds of music in his movie, including Bach, Mozart and Prokofiev, and also a recording of "Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child"; but in addition--and here it is--Blind Willie Johnson's "Dark Was the Night--Cold Was the Ground" (and I should mention in the hymn the line ends, "on which the Lord was laid"). I'm sorry Willie Johnson's version seems to be passing into cliche, but as one of my college professors was fond of pointing out, cliches become so because they are so true we can't stop using them. And so it is with Blind Willie's song; Wikipedia reminds us, "Johnson's recording ... was included on the Voyager Golden Record, sent into space with the spacecraft in 1977, and ... [also] was used in [Carl Sagan's show] Cosmos." The site goes on to mention the song's appearance on The West Wing, Walk the Line, and The Devil's Rejects, and to point out that Ry Cooder, who "based his desolate soundtrack to Paris, Texas" on the song, "described it as 'the most soulful, transcendent piece in all American music.'"

And watching it now, one more thing is added, something that took me completely by surprise, and froze me in my tracks once again: In high school I had not noticed that Pasolini used all kinds of music in his movie, including Bach, Mozart and Prokofiev, and also a recording of "Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child"; but in addition--and here it is--Blind Willie Johnson's "Dark Was the Night--Cold Was the Ground" (and I should mention in the hymn the line ends, "on which the Lord was laid"). I'm sorry Willie Johnson's version seems to be passing into cliche, but as one of my college professors was fond of pointing out, cliches become so because they are so true we can't stop using them. And so it is with Blind Willie's song; Wikipedia reminds us, "Johnson's recording ... was included on the Voyager Golden Record, sent into space with the spacecraft in 1977, and ... [also] was used in [Carl Sagan's show] Cosmos." The site goes on to mention the song's appearance on The West Wing, Walk the Line, and The Devil's Rejects, and to point out that Ry Cooder, who "based his desolate soundtrack to Paris, Texas" on the song, "described it as 'the most soulful, transcendent piece in all American music.'"  Geez; that is a lot of weight to put on a three-minute, wordless "moaning song." But "Dark Was the Night--Cold Was the Ground" can take it--even if I almost can't. Pasolini uses it when the leper approaches Jesus to be cured. I found myself suddenly tearful. How did Pasolini know that, even as a doubting teenager, I was--and still am, despite my vacillations and fear of "God's Silence"--moved more than I can say by the curing miracles, especially those involving lepers, who always scared me when I was a little kid. They were always depicted like Karloff's Mummy--and worse, their disease was all about decay, which made them the original Living Dead, shambling horrors that could enlist you in their hopeless number with a mere touch, like Judas' kiss. And speaking of which: To hear about saints not only caring for but embracing, even kissing lepers, was terrible, because I knew it was expected of me, like being ready to endure Chinese Communist torture, just like those martyred nuns and priests who were getting it plenty while I was safe at home, with clean clothes and hot meals and parents who loved me. Oh, boy. These were heavy loads--and let me say I do not entirely regret them, as dank as they seem. The "problem of pain"--I will be getting to Shadowlands in another post--of course never goes away; it is as central as the problem of love--and so close they end up, at their human best, leading one to the other, completing each other.

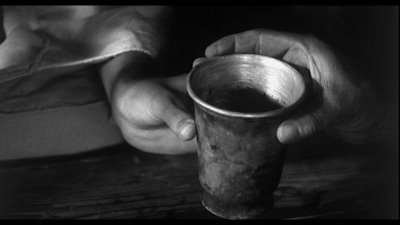

Geez; that is a lot of weight to put on a three-minute, wordless "moaning song." But "Dark Was the Night--Cold Was the Ground" can take it--even if I almost can't. Pasolini uses it when the leper approaches Jesus to be cured. I found myself suddenly tearful. How did Pasolini know that, even as a doubting teenager, I was--and still am, despite my vacillations and fear of "God's Silence"--moved more than I can say by the curing miracles, especially those involving lepers, who always scared me when I was a little kid. They were always depicted like Karloff's Mummy--and worse, their disease was all about decay, which made them the original Living Dead, shambling horrors that could enlist you in their hopeless number with a mere touch, like Judas' kiss. And speaking of which: To hear about saints not only caring for but embracing, even kissing lepers, was terrible, because I knew it was expected of me, like being ready to endure Chinese Communist torture, just like those martyred nuns and priests who were getting it plenty while I was safe at home, with clean clothes and hot meals and parents who loved me. Oh, boy. These were heavy loads--and let me say I do not entirely regret them, as dank as they seem. The "problem of pain"--I will be getting to Shadowlands in another post--of course never goes away; it is as central as the problem of love--and so close they end up, at their human best, leading one to the other, completing each other. And so hearing Johnson's song about Jesus' burial as He cured the leper was particularly moving. I suddenly imagined that Jesus' cures--all the way to poor Lazarus--were moments of poignant indulgence, opportunities to provide for others what He could not for Himself: rescue from the dark night and the cold ground. And more: Signifiers of the Promise. I will not handle this too much; it is fragile, and I need it. But I do love that song, and will not apologize for my tears. And I thank Fr. Jack for showing me Pasolini's movie, and giving me one more light. The last line of the hymn Willie simply moans--because his audience knew the words--enjoins us to "Awake to watch and pray." It is the least we can do; after all, the night is dark, the ground is cold, and we should not leave each other alone.

And so hearing Johnson's song about Jesus' burial as He cured the leper was particularly moving. I suddenly imagined that Jesus' cures--all the way to poor Lazarus--were moments of poignant indulgence, opportunities to provide for others what He could not for Himself: rescue from the dark night and the cold ground. And more: Signifiers of the Promise. I will not handle this too much; it is fragile, and I need it. But I do love that song, and will not apologize for my tears. And I thank Fr. Jack for showing me Pasolini's movie, and giving me one more light. The last line of the hymn Willie simply moans--because his audience knew the words--enjoins us to "Awake to watch and pray." It is the least we can do; after all, the night is dark, the ground is cold, and we should not leave each other alone. *He was played by a grad student named Enrique Irazoqui, who showed up one day to talk with Pasolini about his work--and thank goodness, because that mad Marxist was all set to cast Jack Kerouac or Allen Ginsberg as Jesus. (Annals 'o Civilization Narrow Escape No. 1,345,926!)

*He was played by a grad student named Enrique Irazoqui, who showed up one day to talk with Pasolini about his work--and thank goodness, because that mad Marxist was all set to cast Jack Kerouac or Allen Ginsberg as Jesus. (Annals 'o Civilization Narrow Escape No. 1,345,926!)

No comments:

Post a Comment