As the landscape rushes at you, or the corridors unwind--and the inevitable sudden forms loom or arc down from the sky--you either fall into it or you don't. I did: In a computer far, far away--the mid-1990s--I amazed myself by downloading a free demo of Doom, and, herky-jerking around the slate-Lego architecture, my shoulders unconsciously twisted and my head ducked as demons hissed and spat fire, and grunting soldiers shotgunned me plenty. The "physical" experience of playing made me feel funny--and then I read in Time magazine about "D.I.N.S.": Doom-Induced Nausea Syndrome. If you get close enough to your computer screen and play long enough, your head starts to wrap itself like a fist around your eyeballs and stomach, and, like I said, you fall into it; once again, the eager surrender to persistence of vision.

I have always understood the attraction of video games, especially first-person shooters--but even the ones in which you follow around a car or Angelina Jolie (obligatory "woof!")--because of that nausea, that dizzy hypnotic swirl. I don't play much, but I do remember trying out the first version of Wolfenstein and knowing I was watching a whisper of things to come. Doom, though, is my favorite: simple, scary, satisfying, a dark carnival try-yer-luck. And the subsequent incarnations of the game over the years have grown scarier; a few months ago I rented it, and my kids would play until things got particularly dim and growly, and would hand the controller to me and actually leave the room--and me, to my, ahem, doom. Which it was. (I said I liked Doom; I didn't say I was any good at it.)

Now, I've never been a big fan of that element of video-gaming that asserts the player's need to "control" the story. In fact, I'm fond of exasperating my children by pointing out that video games actually control the player, forcing him/her to follow the proper trails, obey detailed instructions, learn and remember--or else. The video-game urge to control narrative--as illusory as it may be--for me is eminently resistible. It is a desire shared by all gaming kids, from video-heads to live-action-role-playing supernerds, kith and kin of the Dungeons and Dragons and Magic: The Gathering ultra-supernerds, godblessem. Me, I'm happy to let the screen do the work; I prefer a certain passivity, willing to be drawn along by the game's narrative, as simple as it may be. Again, the dizzy feeling I get when I play video games, that home-IMAX effect, is the reward for surrender to the game.

Of course, such swooning also is at the core of the movie-watching experience; we should never forget those earliest movie-goers, yelping as trains rushed at them or the Eiffel Tower's elevator rose. So not only do I not complain when a video game becomes a movie, I understand such an adaptation makes perfect sense. To gripe about the lack of plot in a game-movie is disingenuous, to say the least--not to mention redundant. Keep in mind the free pass fans have given virtually every James Bond movie--and also admit how easily Bond translated to a game. I'm happy if a game-movie captures the essential dual motion of video games, a forward progress built of widening circles, as each new level recreates the architecture of its predecessors in new settings: the corridor becomes the street, the street the coastline, the coastline the jungle trail, and so on. And while the better game-movies recognize the movie-instinct toward plot, they still adhere to the roots of cinema: the level gaze at objects moving parallel with or toward the viewer. Anything beyond such gazing can be almost distracting.

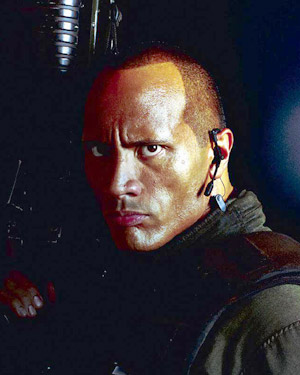

The Doom movie, for instance: It surrenders with honest glee to its game-source, pausing only long enough so that we can decide which character-players we want to live or die, then killing them anyway. Its star, The Rock, inherits the Schwarzeneggar legacy, although The Rock does not distract us with his voice, and he is actually not particularly stiff. Best of all are his eyes. His pro-wrestling career has taught him to stare at his enemies with conviction. "Acting" it may not be, but acting is mostly in the eyes, and so at least he does not irritate with the impression he'd rather be looking at something else. And of course, the movie is famous for its five-minute first-person sequence, which simply allows one to watch the filmmakers play the game. I must admit I've at times enjoyed watching my kids play video games. It is the ultimate in passive viewing. Doom accepts this passivity with complete honesty, and to complain about that is to admit you don't like video games. And while I admit that's a pretty smart thing to do, I have the benefit of watching movies like this with a twelve-year-old, one who knows it's all hollow--oh but momma, that's where the fun is.

The Doom movie, for instance: It surrenders with honest glee to its game-source, pausing only long enough so that we can decide which character-players we want to live or die, then killing them anyway. Its star, The Rock, inherits the Schwarzeneggar legacy, although The Rock does not distract us with his voice, and he is actually not particularly stiff. Best of all are his eyes. His pro-wrestling career has taught him to stare at his enemies with conviction. "Acting" it may not be, but acting is mostly in the eyes, and so at least he does not irritate with the impression he'd rather be looking at something else. And of course, the movie is famous for its five-minute first-person sequence, which simply allows one to watch the filmmakers play the game. I must admit I've at times enjoyed watching my kids play video games. It is the ultimate in passive viewing. Doom accepts this passivity with complete honesty, and to complain about that is to admit you don't like video games. And while I admit that's a pretty smart thing to do, I have the benefit of watching movies like this with a twelve-year-old, one who knows it's all hollow--oh but momma, that's where the fun is.

No comments:

Post a Comment