I was sitting in my office--students outside, working, talking, another level of offices and student areas above me. I was listening to music--a long list of jazz and '40s-'50s vocalists (the iTunes-life-soundtrack effect)--and realized I heard other music, live, someone singing upstairs: "Santa Lucia," high and soft. Maybe a co-worker's child? A student from the choir? I'm not sure; but her voice was clear--"a port in air," as Wallace Stevens might put it--albeit sweetly weak. I turned off my music and listened. One verse, a pause, a second verse. No applause, no approving murmur of voices. Here and gone.

This occurred just as I had begun to think of writing on Jean-Luc Godard's 1962 film, Vivre sa vie (My Life to Live). A "user comment" on the Internet Movie Database asks plaintively for the title of the "catchy" song Nana (Anna Karina), a young woman who falls into prostitution--then further down--plays on the jukebox. More music, also fleeting.

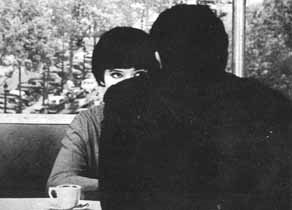

At the risk of sounding a bit too precious, I think Godard's "Film en douze tableaux" shares space with such music. It is elusive, from its twelve-scene structure to its stubbornly still and obscurely placed camera, showing us the backs of heads and blurred reflections, or only one figure, the other off-camera, speaking but absent. The cinema of preterition, in which conclusion is thwarted by concision. Godard seems almost unconcerned with Nana's plight; but as the film moves through its chapters, it extends to Nana a courtesy: By holding back, Godard admits it is not his life he is filming--let alone his audience's--but Nana's, "hers to live," ours to observe--but discreetly; if there is sympathy for Nana, it comes without a proprietary impulse masked as affection.

We know how "Santa Lucia" goes, so we "own" it in that sense. But as I heard it this afternoon, the singer unseen by me and I by her, I was reminded that others' lives play without us--and you can take that in many ways--and sometimes our greatest show of compassion is a respectful distance. I wanted to see Nana more closely--she was so beautiful, and thoughtful, and sad--but Godard knew that the closer I approached her the more I would project my self, my expectations, my needs, onto her; and so he restrained me, for my sake as well as Nana's. I will not tell you, then, what happens to her. In the spirit of Godard's music from upstairs, I too will hold her off to one side, her face turning away, and invite you to listen on your own some time.

No comments:

Post a Comment