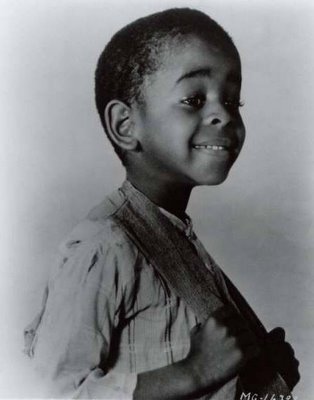

I gave in to a fond indulgence: a DVD filled with Hal Roach's "Little Rascals" shorts, in all their cheerfully brutal glory, with enough nascent racism to make one squirm--but still enter laughing, buoyed by Stymie's doggedly insistent hunger that will never be sated, no matter how many sizzling frypans of eggs and ham or smorgasbord handouts--complete with Arty-choking artichokes and dog biscuits--or sagging sacks of candy--OK, here it comes: Yum, yum, eatumup--he can wolf down. Watching those long-gone children scampering around their nondescript edge-of-Hollywood early-morning locations--scraggly fields, stagnant ponds, dirt paths, alleys and culverts cluttered with handy brickbats suitable for bouncing off dog catchers' and truant officers' bald pates, and of course home to inexplicably available mules--I am once again filled with nervous excitement as they race between the legs of cruel adults, some of whom are actually armed, others merely squinting with Edgar Kennedy-esque certainty of delinquency; and I am filled as well with Stymie's hunger, broad and blatant, but real, even when he literally licks his lips in anticipation, because I understand the feeling: Anything--everything!--but mush.

When I was a kid myself, the Little Rascals were easily recognizable as real children, albeit inhabiting an idealized--or at least stylized--world, particularly because of their appetites: for food, of course, constantly, but also each other. They know how vital it is for children to, like good revolutionaries, hang together to avoid hanging separately. Exclusion from the gang is a bitter, tearful, panicky business; and their friendships demand a calm port after the storms of school and romance, capture and flight. While some adults extend affectionate or charitable hands--the nice ladies whose back porches Stymie approaches to beg for food, or shopkeepers and passers-by who indulge the children's whims--"borrowing" apples for an unsuccessful lesson in arithmetic (doomed to failure because of the apples' presence; they are, after all, food, not academic abstractions)--and of course the lovely Miss Crabtree, still the single most charismatic educator in film history (goodbye, Mr. Chips, you betcha)--most grownups in the Little Rascals world are active threats, far removed from the absolute values of childhood: appetite and loyalty.

The DVD I watched seemed determined to offer a thesis about those values: that they were best expressed in terms of the Rascals' relationships to dogs--particularly the phenomenal Petey, of course, but also a number of other crossbreeds tumbling around, fellow children--or at least creatures of the same world, pursued with ugly unrelenting violence by adults posing as dog catchers simply to make easier their acts of aggression in the War on Children. Petey is even featured in a weird silent short that chronicles in flashback his decision to commit suicide by hanging--assisted by a sympathetic fellow canine--in a telling turn of events, due to his master's betrayal. And true to form it's cherchez la femme, another appetite encountered--but the pursuit of the girl is an adult yearning; no wonder it spells doom. And Petey actually goes through with it, twisting at the literal end of his rope, but is rescued by his repentant master. If you want order--true, of a noisy sort, borne aloft by misunderstandings and a skewed child's-eye view, but order nonetheless--you have to turn your back on the adult world, or it can be lethal: Petey is gassed at the dog pound in another episode--and the fact that the gas canisters were empty does nothing to lessen the cruel extremes Hal Roach's series resorts to in order to test the absolutes that bind the Little Rascals.

The DVD I watched seemed determined to offer a thesis about those values: that they were best expressed in terms of the Rascals' relationships to dogs--particularly the phenomenal Petey, of course, but also a number of other crossbreeds tumbling around, fellow children--or at least creatures of the same world, pursued with ugly unrelenting violence by adults posing as dog catchers simply to make easier their acts of aggression in the War on Children. Petey is even featured in a weird silent short that chronicles in flashback his decision to commit suicide by hanging--assisted by a sympathetic fellow canine--in a telling turn of events, due to his master's betrayal. And true to form it's cherchez la femme, another appetite encountered--but the pursuit of the girl is an adult yearning; no wonder it spells doom. And Petey actually goes through with it, twisting at the literal end of his rope, but is rescued by his repentant master. If you want order--true, of a noisy sort, borne aloft by misunderstandings and a skewed child's-eye view, but order nonetheless--you have to turn your back on the adult world, or it can be lethal: Petey is gassed at the dog pound in another episode--and the fact that the gas canisters were empty does nothing to lessen the cruel extremes Hal Roach's series resorts to in order to test the absolutes that bind the Little Rascals. The more I watch them, and the older I get--and doesn't that work out nicely?--I become convinced that, as stiff and formulaic as they are, these little films resonate. Yes, the Rascals are deeply caught up in bodily functions, material gain (Consider the truant wannabe, Brisbane, who, speaking out of the corner of his mouth--yet another Rascal visual trope--disdains his mother's plans for him to become President in favor of his own dream to become a street car conductor: "Boy, do they take in the nickels!" He listens to a hardworking man at his "grim forge" describing how he dutifully studied and was first in his class, all in the service of his own aspiration to reside in the White House. But as Brisbane observes with finality, "And you ended up a punk blacksmith."), and of course the joys of the chase. But they also seem to yearn for a perfected state, one that provides a justification for their appetites, a kind of vacant-lot-as-Pure-Form, a Rascal-ness, Professor, if you please, that places them out of the reach of starched shirts and outraged dowagers and allows them room to see the world as it is really is--or at least as they are always imagining it, which by the end of the second reel means a full belly, a safe pooch, and arms draped over each others' shoulders, as ready to give one another a kiss as a razzberry, in the safety and freedom of a partly hidden world at knee-level, little but not forlorn.

As Brisbane regrets his truancy, weeping as the Rascals often do--and not only because he has let down his mother and the radiant Miss Crabtree, but because, as an expelled student, he may be free but he is also divorced from the gang--he accepts his punishment: to recite a sickly sentimental poem, a rapturous ode to his teacher. He stands at the front of the room, torturously expelling the awful words, while the other kids howl their cleansing derision, drawing him back--and I don't think into simple conformity to adult authority, but to a far better place, where the clubhouse leans and Petey waits with Spanky--so fond of pointing out deviations from the Code of Loyalty with a sarcastic, drawn-out, "My pal"--and Stymie and Weezer and Farina, while that theme music, surprisingly plaintive, more goodbye than hello, reworks my childhood in its own grainy, mugging, double-take image.

As Brisbane regrets his truancy, weeping as the Rascals often do--and not only because he has let down his mother and the radiant Miss Crabtree, but because, as an expelled student, he may be free but he is also divorced from the gang--he accepts his punishment: to recite a sickly sentimental poem, a rapturous ode to his teacher. He stands at the front of the room, torturously expelling the awful words, while the other kids howl their cleansing derision, drawing him back--and I don't think into simple conformity to adult authority, but to a far better place, where the clubhouse leans and Petey waits with Spanky--so fond of pointing out deviations from the Code of Loyalty with a sarcastic, drawn-out, "My pal"--and Stymie and Weezer and Farina, while that theme music, surprisingly plaintive, more goodbye than hello, reworks my childhood in its own grainy, mugging, double-take image.

4 comments:

does anyone remember the words to the poem brisbayne recited

I haven't looked at this post of mine for a long time--I'm trying to remember the disc I saw these episodes on--and the title of the silent short I mention--but here's this query about the poem--and, thanks to The Little Rascals.net (http://www.thelittlerascals.net/readin_and_writin.html), here's the poem!

High up grew a daffodil

I couldn't hardly reach her

Said I to me, "I think I will

Get it for my teacher!"

I climbed to get the daffodil

Out on a limb so thin

I tumbled down like Jack and Jill

And skinned my little shin

And here's the pretty daffodil

I brought to my dear teacher

I love her dear and I always will

I'm awful glad to meet cha!

Just cutting and pasting this makes me want to watch it again. There are few discs I feel the need to own--thanks, Netflix--but I think the Rascals deserve a place in the library. "So long, Crabby!" indeed.

God bless The Little Rascals.net, who helped me find the disc (Hallmark's "The Little Rasscals, vols. 3 & 4) and the silent short--"Dog Heaven." And lo and behold, the disc was in my Queue. Yum, yum, eatemup!

OMGosh that was the funniest episode!

Thank you!

NJT

Post a Comment