In his Playboy interview a year or so before his death, Jackie Gleason begins a story with something like, "I was in Toots Shore's joint with Salvador Dali. He had that cane with a sword inside, and ..." I don't remember exactly what happened; it doesn't matter. But I say you can't consider yourself "cool" unless you can start a story this way. It's a measure of a celebrity, I guess, but also of the artist, who often places him/herself consciously--if not always purposefully--in a separate world, a "protected station" that allows artists to play and fight with each other in relative isolation--barring the occasional spillover into the square world, where you and I are trying to get to work but are thwarted by some Merry Prankster whose Happening keeps the trains from running on time.

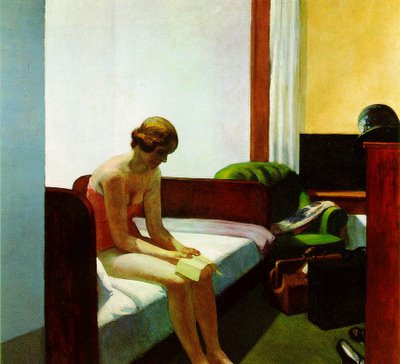

Of course, such disruption can be a good thing. I remember catching John Cassavetes' Husbands (1970) on TV, and being stunned by the seeming disconcern that anyone was watching it, and the hypnotic effect of ignoring me. Cassavetes, Peter Falk and Ben Gazzara spontaneously combusted--but it was a cool blue fire, an enchanted ring. And Edward Hopper's paintings also poleaxed me, as they turned their shoulders from my eyes, forcing me to be satisfied with what they allowed me to see, their steady breath as sad as it was measured. Or Raging Bull, the last noir, as confused and lost as John Garfield in Force of Evil, keeping everybody blind except the audience, if they would only see.

Thinking about these artworks, I return to my irritation with the self-absorption necessary to be an artist. The demands of not only the artists but their artworks is intrusive; again, I'm often just trying to keep moving forward, but this stuff stops me short, and I am suspended between hypnosis and derision. After all, artists make demands on those around them, as do athletes. You better love helping out if you're going to live with either, because they're busy creating, so clean those brushes and replace those divots. This point is driven home for me in Frida (2002), as Frida Kahlo (Salma Hayek) and Diego Rivera (Alfred Molina) trade demands disguised as needs, tossing everything and everyone out with the bathwater. Again and again, I grew irritated by their insistence that the other--or, worse yet, innocent bystanders--make way for whatever Creation was brewing at the moment. I confess there's something conservative in my heart that begrudges such self-absorption. Am I wrong in asserting that the best lives are passed in service?

Thinking about these artworks, I return to my irritation with the self-absorption necessary to be an artist. The demands of not only the artists but their artworks is intrusive; again, I'm often just trying to keep moving forward, but this stuff stops me short, and I am suspended between hypnosis and derision. After all, artists make demands on those around them, as do athletes. You better love helping out if you're going to live with either, because they're busy creating, so clean those brushes and replace those divots. This point is driven home for me in Frida (2002), as Frida Kahlo (Salma Hayek) and Diego Rivera (Alfred Molina) trade demands disguised as needs, tossing everything and everyone out with the bathwater. Again and again, I grew irritated by their insistence that the other--or, worse yet, innocent bystanders--make way for whatever Creation was brewing at the moment. I confess there's something conservative in my heart that begrudges such self-absorption. Am I wrong in asserting that the best lives are passed in service? But Frida, like Cassavetes, Hopper, and Scorsese, cracked its elbow through the window, another burglar of my bluster and indignation. Frida was badly injured when a girl, and suffered numerous operations--and this during the first half of the twentieth century, so you know how much good they did, and how much harm. She was wracked by pain, losing strength, mobility, her baby, some toes, as the years went by. The more I saw her soldier on, drawing in bed, slow with pain, the more I realized she really wasn't asking anything of me. I had no need to feel inconvenienced by the tantrums and double-standard arrogance. It was none of my business. I just needed to look at the paintings, and allow her her pain. A lifetime of illness can begin to look like an artist's life, you know, with its constant demands on those around the sick person, its insistence that everyone see the world through Malady's eyes. When the pain becomes the artwork, I feel ashamed that I complained about the noise and smell. Because if you watch carefully and lay your hands softly but firmly, you are given a life to serve, and can draw strength from the tortured muscles straining beneath your grip.

But Frida, like Cassavetes, Hopper, and Scorsese, cracked its elbow through the window, another burglar of my bluster and indignation. Frida was badly injured when a girl, and suffered numerous operations--and this during the first half of the twentieth century, so you know how much good they did, and how much harm. She was wracked by pain, losing strength, mobility, her baby, some toes, as the years went by. The more I saw her soldier on, drawing in bed, slow with pain, the more I realized she really wasn't asking anything of me. I had no need to feel inconvenienced by the tantrums and double-standard arrogance. It was none of my business. I just needed to look at the paintings, and allow her her pain. A lifetime of illness can begin to look like an artist's life, you know, with its constant demands on those around the sick person, its insistence that everyone see the world through Malady's eyes. When the pain becomes the artwork, I feel ashamed that I complained about the noise and smell. Because if you watch carefully and lay your hands softly but firmly, you are given a life to serve, and can draw strength from the tortured muscles straining beneath your grip.

No comments:

Post a Comment