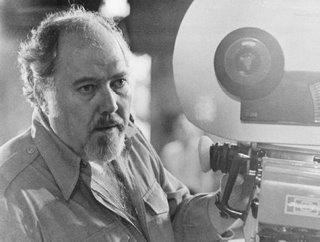

I will simultaneously arise from weeks-long silence and pause the (still-running) Halloween Roundup to pay my respects to Robert Altman, the original meatball surgeon. It's hard to imagine him being born a year before my father: The former's sensibilities seemed so much a part of the good-bad chemicals of post-modern cut-out/up culture, while my Dad was, if I'm to be stuck with this line of comparison at least for another sentence or two, a High Modernist, full of the whiz-bang optimism of a world defined by change. He enjoyed the fact that he was born in a Philadelphia where horse-drawn wagons were common, and was approaching a (never-to-be-realized) old age (gone at 70) in which microchips (and -waves) were as ubiquitous as boredom over space travel. Positivist flux, "all the way down the line."

Altman, on the other hand, seemed in some ways to have sprung out of the '60s forehead both brand-new and all grown up--and gleefully outraged at It All--with M*A*S*H in 1970. And he didn't seem to look back much, barreling along with both guns blazing--and sometimes out of true, wild shots often, all smoke and noise and beautiful overlap, like Buffalo Bill (someone he and Paul Newman took apart messily in 1976, by way of Arthur Kopit's 1969 play) giving Mad Hatter history lessons. As the '70s circus rolled on, I found myself missing his bulls'-eyes (McCabe and Mrs. Miller/1971, Nashville/1975, Three Women/1977), instead lingering on the ones that sometimes seemed like feature-length outtakes fiercely proud that no one was watching (Quintet, 1979)--or unashamed if everyone was, but jeeringly (Popeye, 1980).

The Altman I held was one slippery fish, and either too big to hold on to or too ugly to handle. I didn't always love his movies, but I did always want to see them. And although I still cannot forgive him for trashing Chandler/Marlowe in 1973's The Long Goodbye, at long last I can admire how thoroughly he did so. (Two horrifying words: Elliot. Gould.) So when I saw his beautifully crafted TV version of The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial (1988) or the light-infused, deliberately paced and patched Short Cuts (1993), I would point to them as signs of his greatness, until after a while, it seemed I didn't need Nashville and company, while something like The Player (1992) seemed an Altman movie only marginally, as much his as The Thing from Another World (1951) was Howard Hawks'--which might mean mostly, but only in the set-ups and punchlines. The "real" Altman, you understand, was not interested in filling theaters, just the screen.

I'm glad this is my perception of him: a sideshow of import, an iconoclast who irritated his own generation by encouraging the noisy habits of their children. But a quick glance at Altman's TV work belies another take, with all those episodes of Route 66, Bonanza, Combat!, Maverick, Whirleybirds, Peter Gunn. Perhaps not simply Altman the blissed-out pest, but after all just one of those aspiring Americans reaching adulthood after World War II, often dazed and confused themselves, but workin' on it every day, and hard; the evening lineup as palliative and preamble. So go ahead, now that he's gone: look at Quintet's frozen beauty and the first real live-action cartoon, Popeye, and relax just a little bit in the fit-filled glow of Altman's long and bittersweet grin-and-grimace. (And, while we're on the subject of Buffalo Bills, ask, along with e.e. cummings, "how do you like your blueeyed boy / Mister Death.")

I'm glad this is my perception of him: a sideshow of import, an iconoclast who irritated his own generation by encouraging the noisy habits of their children. But a quick glance at Altman's TV work belies another take, with all those episodes of Route 66, Bonanza, Combat!, Maverick, Whirleybirds, Peter Gunn. Perhaps not simply Altman the blissed-out pest, but after all just one of those aspiring Americans reaching adulthood after World War II, often dazed and confused themselves, but workin' on it every day, and hard; the evening lineup as palliative and preamble. So go ahead, now that he's gone: look at Quintet's frozen beauty and the first real live-action cartoon, Popeye, and relax just a little bit in the fit-filled glow of Altman's long and bittersweet grin-and-grimace. (And, while we're on the subject of Buffalo Bills, ask, along with e.e. cummings, "how do you like your blueeyed boy / Mister Death.")

No comments:

Post a Comment