Before the Halloween Roundup begins, I need to clean the cinematic house and write about a movie that even now, four days after watching it, continues to grow in my head--no, echo, a low reverberation of sweet melancholy and last glimpses, a middle distance sound that does not want to fade away. I once heard a recording--I think I downloaded it from a site called epitonic.com (I've been trying to get to it this morning, with no luck)--made by lowering a musician--a trombonist, if I recall--into a big empty cistern or water tower, a circular one, to play single notes. The acoustics of the space generated something like a 90-second reverb, so each note played within that interval overlapped with the previous for a long time, and so on. It was sonorous, a little mysterioso, almost silly, even irritating, but in its way beautiful.

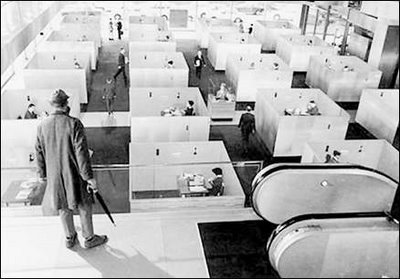

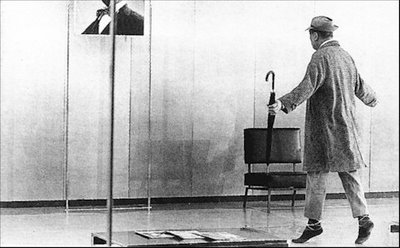

Jacques Tati's character, Monsieur Hulot, part Chaplin, part Keaton, an essentially silent character in a world of increasingly complex and subtle sounds, appears in three films: Monsieur Hulot's Holiday (1953), Mon Oncle (1958), and Play Time (1967). Tall and almost blocky, with his hat and long raincoat and umbrella and pipe, Hulot, like that trombone in the cistern, stretched his note long, but with an inevitably diminishing tone. Just look at the titles. The first seems to belong to him, but even at the start it is his vacances on which the film focuses. In the second he is not primarily himself, but someone's uncle. And in the third, nine years later, he has all but disappeared, that 90-second reverb gone at last in the midst of another kind of holiday, a single long Parisian night, a "play time" that begins in a lengthy first act of blue steel and geometric severity, leading toward a chaotic symphony for jazz nightclub and tourism, and ends with perfect calliope diminuendo (if such a thing is possible) as Paris, which in the film had been cold and impassive throughout the day, then raucous and grating in the nightclub--while joyfully falling apart, chair by chair, garment by garment, wall by wall--suddenly comes to life at dawn, transforming itself into a rush-hour carousel, a country fair that fades as the tourist bus leaves the city; at this last moment, Hulot finds one more opportunity for the gentle offering of a gift (a scarf for a young woman, a tourist he had befriended during the long night of free jazz and dismantled architecture), and the curve of a spray of small flowers he had put in the giftbox mimics the branching ultramodern streetlights marching outside the bus's windows, a last fond dream that Paris (that is, the modern--heck, the American--world) just might have hidden in its monolithic polish and metallic hiss a memory of the plaintive-but-happy notes of a cafe accordion, accompanied by a fine but thin--and a little tipsy--voice singing, after everything closes down.

Someone out there wrote that watching Play Time takes the same kind of patience one needs for Kubrick. An apt comparison, if only because the film was released one year before 2001, and both share a leisurely pace and almost cold and--as Terry Jones mentions in his fine introduction to Play Time on the Criterion DVD--alienating tone. The nightclub scene, for instance: A jazz ensemble takes the stage, and plays almost constantly throughout the sequence, a half hour or so, with peppy but grating percussiveness. I'm tempted to be reminded of the opening of Scorsese's New York, New York, in which De Niro's Jimmy Doyle insistently tries to pick up Liza Minelli's Francine Evans, while "Opus Number one" plays in the background; the music follows the rhythms of Doyle's efforts to win over Francine, as in Play Time, where the band falls apart as the nightclub does. Still, perhaps the better musical comparison would be to the "Jupiter and Beyond" squeaks and howls of Kubrick's 2001.

Someone out there wrote that watching Play Time takes the same kind of patience one needs for Kubrick. An apt comparison, if only because the film was released one year before 2001, and both share a leisurely pace and almost cold and--as Terry Jones mentions in his fine introduction to Play Time on the Criterion DVD--alienating tone. The nightclub scene, for instance: A jazz ensemble takes the stage, and plays almost constantly throughout the sequence, a half hour or so, with peppy but grating percussiveness. I'm tempted to be reminded of the opening of Scorsese's New York, New York, in which De Niro's Jimmy Doyle insistently tries to pick up Liza Minelli's Francine Evans, while "Opus Number one" plays in the background; the music follows the rhythms of Doyle's efforts to win over Francine, as in Play Time, where the band falls apart as the nightclub does. Still, perhaps the better musical comparison would be to the "Jupiter and Beyond" squeaks and howls of Kubrick's 2001.In any case, Play Time refuses to fade away. I am not as lucky as Hulot, who gets to stay behind, perhaps lost in a France that looks almost nothing like the strolling ease of Monsieur Hulot's Holiday, but still able to recede (maybe to some last corner of his Paris-that-was, a city as small town, all winding streets and stray cats and children), his owlish half-smile tentative but secure. No, I travel with the bus, back toward the airport where the movie began (let me add in passing, a pre-Spielberg Terminal of confusions and missed connections of all kinds), having never seen Paris' old-time charms except in plate-glass reflections, more a memory of a memory. It is a long goodbye from Tati, from 1953 to 1967, but we can still see Hulot waving, smaller as we move away, but never disappearing.

No comments:

Post a Comment