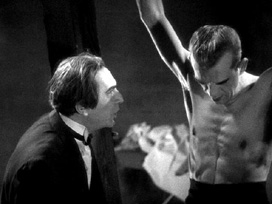

As I settled in to watch The Sentinel (1977), Michael (Death Wish) Winner's post-Rosemary's Baby vulnerable-waif-in-creepy-brownstone effort, I asked myself why I had it in my head that this was a good movie, one I was getting ready to watch for maybe the third of fourth time. On the surface, it was the same old story for me: the memory of a striking image, a mood, a feeling. For The Sentinel it is the effect of a ghostly naked old man passing silently through a darkened room, inches from the heroine, close enough to give us all the shivers. The Ghostly/Ghastly Visitation, the matter-of-fact appearance of the hellish. Good enough?*

Well, once the movie started, I was assured--and not so sure. It chaffed with everything itchy about those polyester '70s, from the giant posters and pastel upholstery to the chrome and indoor fronds. And everyone looked a bit ill, photographed with that crappy (Kodak?) filmstock that seemed worn-out when it was new, ready to fade and fall apart at the slightest change in barometric pressure. And everybody's attitude was slightly nasty, so ready to disdain and dismiss. (There's something to be said for '90s PC-ness, despite all its bad press; at least it urged us not to be so rude.) I figure being in a horror film's bad enough; does the poor heroine (Cristina Raines) really need Ava Gardner and Chris Sarandon (and although I remember him fondly--if that is the right word to describe a vampire--from Fright Night (1985), my view of him will now always be tainted because my wife commented, "He doesn't have a nose!" I think it was the camera angle, but things won't be the same again--between me and Chris, that is; my wife is another matter) getting all abrupt at her? Overall, I found plenty that irritated.

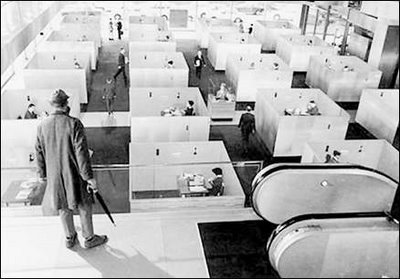

But then I suddenly recalled why The Sentinel was such a guilty pleasure: It was situated right there at a great and grating turn of the Hollywood wheel of fortune, as the last remnants of the studio era gave way to actors who would soon burn--at various levels of brightness and heat--some even now, others at least for a while (and it surely is a sign of age to be an adult witness to rising stars' falls). So there was the aforementioned Ava Gardner flouncing around while Jeff Goldblum acted like a fashion photographer; and Martin Balsam puttered about his professorial digs while Beverly D'Angelo panted in autoerotic ecstasy (oh, those hapless '70s; more on this in a bit); and Eli Wallach grumbled cop-talk while Christopher Walken(!) stood in the background, receiving a number of closeups I can only explain by assuming that Michael Winner, like the rest of us, couldn't stop looking at Walken's friendly, feral face; and Arthur Kennedy and Jose Ferrer and John Carradine guarded the gateway to Hell while Tom Berenger and Nana Visitor (Kira from Star Trek: Deep Space 9) innocently moved in to the new apartment building/gateway to Hell. I suppose this kind of thing still goes on, especially in made-for-cable movies, but the '70s seemed to be a particularly campy-depressing promenade of last gasps and first cries--although, and this should be no surprise, Burgess Meredith rises triumphant, cat in arms and birdie on his shoulder, as the indulged elderly gay man who, for a time, seems so charming.

For a time. Because the other thing that struck me (like a low blow) about The Sentinel was its attitudes towards the sexual. Of course, sex equals death in horror films; but in this masochistic movie it seems that sex equals degeneration. The heroine's aged father drives her to attempted suicide after she catches him in bed with two prostitutes; when she sees his shade wandering around the Old Dark Apartment Building, she tells a priest it makes her think she should try suicide again. And, as I mentioned earlier, Beverly D'Angelo, Sylvia Miles--and even the de-gendered cutie-pie Meredith--all signal not only sexuality but homosexuality-as-depravity--and damnation, since we find out they are all souls on some kind of shore leave from Hell. Not to be too obvious about the emerging metaphor here, but I can't help seeing this film as a record of '70s self-loathing gravitating toward self-destruction; after all, 1977 is just a few helpless breaths away from AIDS, and in retrospect The Sentinel seems ready to lay some nasty blame. Feh; I think I've just found the least savory Halloween Roundup entry so far--and if you glance at the previous six, that's saying something--and, with its cold heart and homophobic little mind, I say to Hell with it.

For a time. Because the other thing that struck me (like a low blow) about The Sentinel was its attitudes towards the sexual. Of course, sex equals death in horror films; but in this masochistic movie it seems that sex equals degeneration. The heroine's aged father drives her to attempted suicide after she catches him in bed with two prostitutes; when she sees his shade wandering around the Old Dark Apartment Building, she tells a priest it makes her think she should try suicide again. And, as I mentioned earlier, Beverly D'Angelo, Sylvia Miles--and even the de-gendered cutie-pie Meredith--all signal not only sexuality but homosexuality-as-depravity--and damnation, since we find out they are all souls on some kind of shore leave from Hell. Not to be too obvious about the emerging metaphor here, but I can't help seeing this film as a record of '70s self-loathing gravitating toward self-destruction; after all, 1977 is just a few helpless breaths away from AIDS, and in retrospect The Sentinel seems ready to lay some nasty blame. Feh; I think I've just found the least savory Halloween Roundup entry so far--and if you glance at the previous six, that's saying something--and, with its cold heart and homophobic little mind, I say to Hell with it.*Writing this sentence, I was reminded of a friend's email about seeing the documentary Henri Langlois: Phantom of the Cinematheque, and recounting Langlois' comment about Vincente Minelli's The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, that it may not have been a good picture, but there were a couple of memorable scenes, so for him "the rest doesn't matter." I am in good company--and I just Netflixed the doc to bask in the glow. Thanks, Mike.