Billy Wilder knew how to walk the line between Hollywood schmaltz-farce (onomatopoeic flatulence intentional) and full-blown moral dyspepsia. At once breezy and nasty, his best comedies smile at you and hold your chin in one hand while cracking you across the cheek with the other. So sometimes it's hard to tell if you were watching comedy or tragedy--Sunset Blvd. (1950) is probably the irresistible but fetid apex of this tendency, followed by the more serious but still corrosively outrageous Ace in the Hole (1950) (and would somebody please get this one back on DVD? Or at least get Turner Classic Movies to run it, again and again?). I can think of few people in--or near--Hollywood in the '50s who seemed so ready to dismantle the studio system from within.

While I'd like to linger on the pictures mentioned above--and many others--having just seen Irma la Douce (1963) I'll just consider his work with Jack Lemmon, which is of course justly legendary, especially Some Like It Hot (1959) and The Apartment (1960). So last night I settled in and fired up Irma, ready for another Wilder sex farce.

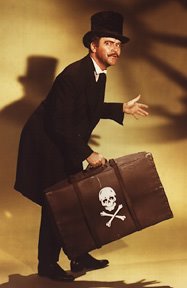

Let me first admit I should've known better. I noticed a running time of two and a half hours, my first warning. Could I stand that much Lemmon? He is a sight to behold, but there's something about his comic performances--you can also see it in Jim Carrey--that can be grating. He is almost too quick, too snappy. And there's a hysteria lurking that can be either hilarious--his morning-after maraca-shaking ecstasy after receiving Joe E. Brown's proposal of marriage in Some Like It Hot--or strained--his British Lord disguise in Irma la Douce--with an accent reminiscent of his later performance in 1965 as Professor Fate in The Great Race--OK, a movie I loved as a kid (for years afterward, my sister and I would echo his outraged response to a wake-up call--"Up and AT 'em!? Up and AT 'em!!?"). But still.

Let me first admit I should've known better. I noticed a running time of two and a half hours, my first warning. Could I stand that much Lemmon? He is a sight to behold, but there's something about his comic performances--you can also see it in Jim Carrey--that can be grating. He is almost too quick, too snappy. And there's a hysteria lurking that can be either hilarious--his morning-after maraca-shaking ecstasy after receiving Joe E. Brown's proposal of marriage in Some Like It Hot--or strained--his British Lord disguise in Irma la Douce--with an accent reminiscent of his later performance in 1965 as Professor Fate in The Great Race--OK, a movie I loved as a kid (for years afterward, my sister and I would echo his outraged response to a wake-up call--"Up and AT 'em!? Up and AT 'em!!?"). But still.  For quite a while, though, Irma shone. The location shots and sets were enchanting, the Technicolor typically mind-bending--this is a movie about streetwalkers, and it is a sight to see them lined up in their blues and pinks and oranges--and Irma's signature green, both stockings and hair ribbon--to match her underpants, as she informs Lemmon's erstwhile upright gendarme, Nestor. And Shirley MacLaine's Irma is pitch-perfect, a matter-of-fact, so-what sex-kitten in an almost restrained performance--well, as would be any next to Lemmon's--her insouciance about her profession balanced nicely with her douce urge for peace and quiet, and a little peppermint tea. And Lemmon is often hilarious, aided by the always-dependable Lou Jacobi as the multi-faceted (according to him) Moustache, who bought a bar named "Moustache" and felt it was cheaper to actually grow a mustache than change the sign, and who constantly claims one fascinating past after another, providing the movie's motto and tagline, "But that's another story." All in all, a perfectly wicked-but-safe scenario.

For quite a while, though, Irma shone. The location shots and sets were enchanting, the Technicolor typically mind-bending--this is a movie about streetwalkers, and it is a sight to see them lined up in their blues and pinks and oranges--and Irma's signature green, both stockings and hair ribbon--to match her underpants, as she informs Lemmon's erstwhile upright gendarme, Nestor. And Shirley MacLaine's Irma is pitch-perfect, a matter-of-fact, so-what sex-kitten in an almost restrained performance--well, as would be any next to Lemmon's--her insouciance about her profession balanced nicely with her douce urge for peace and quiet, and a little peppermint tea. And Lemmon is often hilarious, aided by the always-dependable Lou Jacobi as the multi-faceted (according to him) Moustache, who bought a bar named "Moustache" and felt it was cheaper to actually grow a mustache than change the sign, and who constantly claims one fascinating past after another, providing the movie's motto and tagline, "But that's another story." All in all, a perfectly wicked-but-safe scenario. I also duly noted its Wilder-trademarked unashamed cynicism toward social-sexual mores, at least as he sees them. The movie forgives, even defends, prostitution, toeing the "victimless crime" line--while tagging only one villain, the pimp, whose violence seems out of place in the girls'-club gay abandon of the streetwalkers' lives. At one point Moustache muses, "Shows you the kind of world we live in. Love is illegal--but not hate. That you can do anywhere, anytime, to anybody. But if you want a little warmth, a little tenderness, a shoulder to cry on, a smile to cuddle up with, you have to hide in dark corners, like a criminal. Pfui." Well, it's a relief to know that the prostitutes provide such soft service. Ahem. But I liked the oblique digs at social double standards. In fact, Wilder gives Moustache a central role, as he comments on, aids and abets, encourages and critiques. My favorite line is one he delivers to Nestor before the gendarme is fired for raiding the prostitutes' hotel--with the chief inspector in attendance. Moustache disdains Nestor's oblivious attitude toward the corruption and turmoil around him (Nestor's previous police assignment was at a children's park), noting, "Life is total war, my friend. Nobody has a right to be a conscientious objector."

I also duly noted its Wilder-trademarked unashamed cynicism toward social-sexual mores, at least as he sees them. The movie forgives, even defends, prostitution, toeing the "victimless crime" line--while tagging only one villain, the pimp, whose violence seems out of place in the girls'-club gay abandon of the streetwalkers' lives. At one point Moustache muses, "Shows you the kind of world we live in. Love is illegal--but not hate. That you can do anywhere, anytime, to anybody. But if you want a little warmth, a little tenderness, a shoulder to cry on, a smile to cuddle up with, you have to hide in dark corners, like a criminal. Pfui." Well, it's a relief to know that the prostitutes provide such soft service. Ahem. But I liked the oblique digs at social double standards. In fact, Wilder gives Moustache a central role, as he comments on, aids and abets, encourages and critiques. My favorite line is one he delivers to Nestor before the gendarme is fired for raiding the prostitutes' hotel--with the chief inspector in attendance. Moustache disdains Nestor's oblivious attitude toward the corruption and turmoil around him (Nestor's previous police assignment was at a children's park), noting, "Life is total war, my friend. Nobody has a right to be a conscientious objector." But Irma la Douce ends up being one long campaign, troops. As the plot thickened--like an untended bearnaise--and Lemmon ranted, I longed for an end. And while each scene had its moments, Wilder seemed to indulge too often in real-time sequences that stopped the picture dead. It almost seemed as though he felt he was under the desired running-time and was trying to pad scenes, rather than accepting the responsibility to check plot-bloat--and Lemmon-izing--and finally end the damn thing. Again, I kept finding myself smiling at choice moments, but you know the picture's in trouble when you keep checking the "time remaining" display on the DVD player.

I wish I had had the wherewithal to watch it in bits and pieces; I probably would've liked it more in 45-minute increments. And despite what I've written, I do recommend MacLaine's and Jacobi's--and all right, about 70% of Lemmon's--performances. And Marguerite Mannot's and Andre Previn's music is pure early-'60s exotica Paris cafe. All in all, a movie that could've been. But that's another story.

I wish I had had the wherewithal to watch it in bits and pieces; I probably would've liked it more in 45-minute increments. And despite what I've written, I do recommend MacLaine's and Jacobi's--and all right, about 70% of Lemmon's--performances. And Marguerite Mannot's and Andre Previn's music is pure early-'60s exotica Paris cafe. All in all, a movie that could've been. But that's another story.

No comments:

Post a Comment