As I watched Steven Spielberg's procedural-from-hell, Munich, an odd echo bounced from another movie, a structural feature, like a particularly vaulting ceiling, that slid into my head: Richard Brooks' In Cold Blood (1967), for its part echoing Capote's "nonfiction novel," in that, as Dick famously promises Perry, "honey, we'll blast hair all over them walls"; but, in one of the most expertly crafted, poignantly suspended, and ruthlessly executed versions of one of the oldest strategies of narrative, it makes us wait, and wait, and wait, until we're sick of waiting--and don't you wish, even better, sick of ourselves for our impatience? As we are led toward something awful, but made to want it, then made ashamed for our desire, we fall again into a trap as time-worn-but-true as Oedipus' foregone revelation or Hamlet's authorized revenge. It is unfair of Capote--and Sophocles, and Shakespeare, and, in Munich, Spielberg--to play both sides. But then again, they're the only sides we have, and fool me twice so I'll know who's supposed to be ashamed.

We know--or should--what happened to the Olympic team in 1972, with sportscasters fittingly the messengers of decline and horror, regular guys like Jim McCay telling us flatly that it's just when you thought you could hope for the best that you get the worst. And Spielberg lets us know from the start, even if we don't remember our history (and I guess 1972 is history now)--but like Brooks/Capote, Spielberg, makes us wait. At its worst, such a move can be a cruel appropriation of the sorrows of the dead and our lip-smacking appetite for death, the big payoff. And reading/watching In Cold Blood, we can feel the manipulation. Then something happens: the narrative parts, not just for the blood on the walls, but for our own good, and provides a glimpse into the abyss, with that black reflection rippling down there and just enough light to see ourselves.

We know--or should--what happened to the Olympic team in 1972, with sportscasters fittingly the messengers of decline and horror, regular guys like Jim McCay telling us flatly that it's just when you thought you could hope for the best that you get the worst. And Spielberg lets us know from the start, even if we don't remember our history (and I guess 1972 is history now)--but like Brooks/Capote, Spielberg, makes us wait. At its worst, such a move can be a cruel appropriation of the sorrows of the dead and our lip-smacking appetite for death, the big payoff. And reading/watching In Cold Blood, we can feel the manipulation. Then something happens: the narrative parts, not just for the blood on the walls, but for our own good, and provides a glimpse into the abyss, with that black reflection rippling down there and just enough light to see ourselves. Given its narrative structure, Munich takes on the feel of a Kubrick movie--or maybe a Hitchcock movie remade by Kubrick: It lays out the state of things, and backs away so we can get a better, grimmer view. But there is also enough Spielberg left to push us, like Sophocles pushes Oedipus, to pity, both in the giving and receiving. So maybe there is not much Kubrick after all: just a cold touch that refuses to let go of the back of our necks, forcing us to see, with, again, a devilish dab of Hitch, as we yearn to see the executions in their details, until we side with the careful preparations made and tense challenges faced by the--I want to say "villain," but between Kubrick and Hitchcock and Shakespeare and Sophocles, there's so little room to see which is which--good guy, bad guy--that in the end the suspended death of the athletes seems not just inevitable but universal, and not just political but personal.

Given its narrative structure, Munich takes on the feel of a Kubrick movie--or maybe a Hitchcock movie remade by Kubrick: It lays out the state of things, and backs away so we can get a better, grimmer view. But there is also enough Spielberg left to push us, like Sophocles pushes Oedipus, to pity, both in the giving and receiving. So maybe there is not much Kubrick after all: just a cold touch that refuses to let go of the back of our necks, forcing us to see, with, again, a devilish dab of Hitch, as we yearn to see the executions in their details, until we side with the careful preparations made and tense challenges faced by the--I want to say "villain," but between Kubrick and Hitchcock and Shakespeare and Sophocles, there's so little room to see which is which--good guy, bad guy--that in the end the suspended death of the athletes seems not just inevitable but universal, and not just political but personal. I won't digress too far, but something about Spielberg lately makes me think he keeps making 9/11 movies, from Minority Report's fruitless, horror-movie urge to be safe, to War of the Worlds'--well, everything--and culminating in Munich, thrusting us to shared guilt, relentless as a corridor of blood you don't need the shine to see.

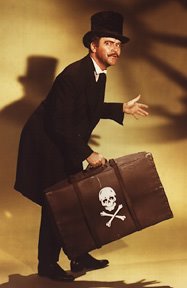

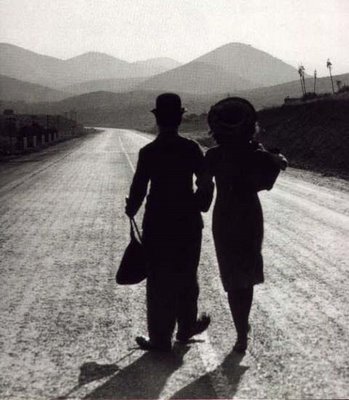

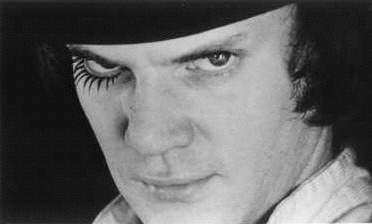

Above: Hitchcock casts his Frenzy-ed gaze on the Last Thing.